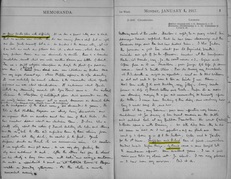

Jan Gordon's diary from 1917,

in his minuscule handwriting,

Jan Gordon's diary from 1917,

in his minuscule handwriting,

The Seeds of Obsession, and the growth of a quest.

One day in 1979 I entered a small second-hand book shop in Crystal Palace, South London. It was a small decrepit and old fashioned kind of shop the like of which is probably now extinct. The erudite owner was a lean bespectacled chap with a stereotypical curly collar. Apart from books his stock seemed to be the overflow of his hobbies, fossils and military badges. I was a regular caller at the shop searching for interesting travel books. Never having had the wherewithal to travel I was an avid armchair traveler and had previously found items of interest here.

On this particular day my attention was caught by two books, fittingly tucked up together, for they were by the same co-authors. I paid my £1.25p or 25 shillings, for one of them,as the curly collared proprietor persisted in the dual pricing of all his stock, even though this was some years after the tragedy of decimalisation had hit us.

The title of that book was Two Vagabonds in Languedoc, the authors Jan and Cora Gordon. The book had that nice comfortable appeal that certain books have; cloth-bound with a distinctive binding, the pages thick, hand cut, with a square block of solid old fashioned type set squarely on each wide margined page. Scattered throughout the book were illustrations by the authors.

I was immediately enamoured of the book and its prose… old fashioned, eccentric but elegant and with an understated gentle humour.

It was a friendly book which felt good in my hand. What better reason to buy any book?

I read parts of it aloud to my wife that evening. We were passing through a stressful phase in our lives and we both found this habit relaxing. She too was immediately enchanted, and when I told her of its shelf companion I had left behind she urged me to return and grab it. So the next day another 25 shillings was spent and Poor Folk in Spain was reunited with its sister book.

This addition merely served to whet our appetite for more knowledge about the authors. It’s no exaggeration to say that I was smitten by these two books; a deeper impression was made on my soul than by any other books I had read. Such was the immediate hold of these books I was avid for more information about the authors; I worked out that there was a slight possibility that they may even have still been alive.

This was all the more curious as never before had I felt this compunction; a book read was a book read, and I had enjoyed it or not, to varying degrees. With the better received books I would have sought others from the same author perhaps; maybe thought, “Yes. I would like one day to visit that spot”, but never had I felt such a compulsion on to make a physical connection with the writers.

A small panel in the front of ‘Two Vagabonds’ spoke of a number of other books by the same authors. I drew a blank at the curly collar book shop but a visit to Bromley Central Library produced the British Library list and a whole list of Jan and Cora books. A search began and via several book sellers only a short time elapsed before a dozen titles describing their travels from Lapland to Spain, from Portugal to Albania and the USA were safely housed on my shelves.

The obsession was only fueled further … who where this couple? What happened to them? Were they still alive? The only mention I could find at first was in entries in the library copy of ‘Who Was Who’, and inked in were the notes … died 1944 … died 1950.

So that was that then. No chance that I could ever speak to either.

But maybe they had had children, they would know more.

I reasoned that the best place to start looking for a dead person was at the point of their last recording, in this life anyway, and a little grubbing about in the mêlées of the Public Records births deaths and marriages office and St Catherine House brought forth some terse facts and names; then the ever useful local library gave up their obituary notices. Thus I had a brief outline of where they lived, what they did and when but little else.

So I made a pilgrimage to Clanricarde Gardens in Notting Hill, their last home where they lived from 1932 to the end of their lives, and thence to the crematorium where their travels finally ended.

I must confess I had a lump in my throat as I sat in the garden of remembrance. I felt that I had grown close to this remarkable couple through their books and it seemed just too anticlimactic an event; too unfinished a quest.

So I sat for a while looking at the kaleidoscope of crocus blossoms that carpet the memorial lawn where their ashes are scattered; a field of impressionistic colour quite fitting as the last resting place for two artists.

“Well, I thought, that’s it” and returned home.

But maybe the ashes of Jan and Cora that fed those crocuses provided a little pollen to encourage the flowering of my thoughts. For, far from being at the end I was at the beginning, it was merely the starting point of a quest that is still blooming.

and then on my the way home I thought……” I wonder where their paintings are?”

The Seeds of Obsession had germinated........

Standing amongst the crocuses in the Spring of 1980, at Golders Green crematorium where the ashes of Jan and Cora Gordon had been scattered some 30 years previously, I honestly thought I had reached the end of my quest for this remarkable couple. In fact it was the beginning of a lifetime’s endeavour.

Since I had picked up the copies of 'Two Vagabonds in Languedoc' and 'Poor Folk in Spain' in 1979 I had become enchanted by these two books. As an avid armchair traveler I would devour any travel book I could find, but no author had caught my imagination as these did, so I energetically and often expensively sought out their other titles.

This developed into a true obsession where all was grist to my mill. I sought out lost and misplaced art work, tracked down relatives and generally hounded anyone with living recall about them. Nothing was safe, so that now my coffee cup rests on a tile from the fireplace of their last home in Notting Hill, near to the brass door number of their flat.

The more I found out about them the more I mourned what has been lost.

Jan kept diaries from his early days and carried a camera everywhere with him.

All is lost.

Only two fragmentary diaries survive from the 1917–18 era, gifted to me by his nephew the late Michael Yapp then living in Jamaica.

Their collection of musical instruments, including those so often mentioned in their books and which accompanied them on their travels, lie jealously guarded yet mouldering unloved, in the barn of a warehouse annexe of the South London museum to which they were entrusted.

Yet some several hundreds of their paintings survive: some in the Wellcome Institute; some in the Imperial War Museum; a scattering in various provincial galleries; many in the keeping of friends and relatives, every one of whom has nothing but fond memories of them. Invariably a smile will cross their faces as they recall ‘Aah, yes . . . Jan and Cora . . .’

So, who were they?

Born the son of a parson in 1882 Godfrey Jervis Gordon was educated at Marlborough College, Wiltshire, in keeping with its status as a college for the sons of clergy. His father was a scion of a wealthy Midlands family, his grandfather a one-time Mayor of Litchfield, but by the time Jan was born this wealth had become so very thinly spread amongst the huge extended family, all living off inherited capital, that Jan, as he had become known at college, was having to establish himself in a career. Influenced by his family’s connections he mistakenly elected to become a mining engineer, seduced as he says ‘by the sweet logic of mechanisms . . .’

Cora Josephine Turner, later known always as Jo, had been born three years earlier in Buxton, Derbyshire, the youngest daughter of the locally noted Frederic Turner, himself the son of Samuel Turner to whom a monument still stands in Buxton.

Dr Frederic Turner was a stereotypical Victorian father, a GP, JP and workhouse guardian, who was much-loved by his patients yet who ruled his home with a rod of iron. Despite his display of temper in the face of Cora’s refusal to be bullied into becoming an unpaid nurse, nannie and housekeeper to her Fathers new children by his second wife,and so ending her days as a spinster of the parish, he finally agreed to her going to the Slade School of Art to study the subject for which she had already shown such talent.

While Cora was studying at the Slade School of Art, Jan had unenthusiastically embarked on a doomed bid to make a fortune mining tin in the Malay, his limited enthusiasm further dampened by his disquiet at the way the industry was run and his distaste at the exploitation of the local labour force. Nor did he endear himself to his employer when he was found sketching the fire that burnt down the mine buildings instead of endeavouring to save them.

A small legacy from one of his many maiden aunts enabled him to return to London and study for a while under Frank Brangwyn at the Kensington School of Art. Fate and events conspired to send both Jan and Cora independently to Paris.

Thus 1906-07 found them both separately cast adrift on the shores of Montparnasse, at that time just beginning to oust Montmartre as the artists’ chosen refuge. A growing but somewhat introspective Anglo-Saxon community centred around the many cheap studios and academies brought them together.

Glimpses of their life before 1914 were few and far between at first but a widening circle of contacts has revealed some interesting information, of which more later.

They lived in and around the very hub of Montparnasse; they once took a studio in the very building that had recently housed Alphonse Mucha; they frequented the Closerie des Lilas, where they met with Picasso and ‘ . . .all the leading and lesser lights of the modern art movement . . .’ Did they ever trip over Modigliani lying drunk somewhere; did they regard him as a drunken nuisance or would they have spent a few francs on one of his sketches in the Dôme café? Did they share a table with the young Hemingway? Did Joyce sponge off them? Were they ever admitted to Gertrude Stein’s sanctum? They would have known of her and her art interests through Nina Hamnett, with whom Jan studied and of whom he was quite fond.

What of all the other characters and artists who used the Carrefour Vavin as their rendezvous? Jan initially lived in a hotel in the street behind the Cafe du Dôme and painted in the Luxembourg gardens, while Cora was a regular student at Colarossi’s academy in the Rue de la Grande Chaumière. Did Cora meet up with Arthur Ransome, who lived in the same block of studios at 9 Rue Campagne Premiere? She certainly knew him as a girl and he may have been the subject of her first girlish love. All such tantalising possibilities remain unknown, the meat I have long striven to put upon the bones of what I have been able to discover about their early life in Paris.

It was the 1914-18 war that stunted their nascent artistic career, yet kick-started their literary career. They had begun to be noticed for their art when the war intervened. Jan was classed as unfit for military service but volunteered for service with the Red Cross in Serbia - how and with whom makes an amusing story of its own (see 'Jan and Cora in Serbia 1914-15' on this site).

On their return to London after the hardships and adventures alluded to above, Jan and Jo were sorely in need of some income and wrote about their adventures in the Westminster Gazette, which in turn led to a commission to write ' The Luck of Thirteen' followed by 'A Balkan Freebooter', a transcript of a Balkan adventurer’s life story.

Jan, who by then had been ‘directed’ into war work, spent 18 months making aeroplane engine parts at Rolls Royce, Derby, but still managed to write numerous articles about art for New Age, New Witness, Nation, Country Life and others. He then went on to work on dazzle camouflage schemes for ships at the Royal Academy, for which he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve.

1919.......

As soon as they were able, funded by Jan’s war gratuity and what he received as official war artist for the Navy Medical Section, they returned to Paris and thence to Spain. Jan had conceived a passion for the Spanish guitar during the war and was determined to sample the music of this instrument at source, along with Jo, who was an accomplished player of violin and piano, having studied at the Manchester Conservatory of Music.

The foundations of their unmistakable writing style were laid in Spain with their two books 'Poor Folk in Spain' and 'Misadventures With a Donkey'. No guide book plagiarism here, no ruins, no church entrails, no socialising with expatriates; Jan and Jo recorded everyday life and trivia and the characters they met with humour, neither condescending nor patronising, though one must sometimes remember that certain flavours of Jan’s phraseology that these days would be considered non-PC are but a reflection of the education and attitudes of an England now a century past. Both these books are as highly regarded in Spain for their observations of ordinary daily life and customs contained therein, as is the Languedoc book in Najac. ‘Poor Folk’ is used to this day to illustrate the complexities and pitfalls of older English grammar and usage in the English department at Murcia University.

At the end of the war, a small service gratuity enabled them to return to their Paris studio. It was now that they decided to combine their literary and artistic skills to research, write and illustrate their first travel book, 'Poor Folk in Spain', published in 1922. The following year, they returned to Spain, this time trekking across the southern half of the country with a donkey and cart. 'Misadventures With A Donkey in Spain' was very well received by the critics, with several reviewers comparing it favourably with Stevenson’s Travels with a Donkey. Hard on the heels of this success came publication of 'Two Vagabonds in Languedoc'. 1925

The Twenties proved to be a bountiful era for the Gordons. Their travel books helped fund Jan’s novels, 'Buddock against London' and 'Girl in the Art Class', a thinly disguised biography of Cora, 'Beans spilt in Spain', a novel largely inspired by events they had not recorded in their Spanish books, and his critical reputation was further enhanced by the publication of 'Modern French Painters' in 1922. Meanwhile, their wanderings took them to Sweden in 1924, Albania in 1925 and Portugal in 1926.

Their growing reputation in the USA led to a grand tour there in 1927-28 but Jan suffered a heart-attack halfway through and on return to Europe they decided that their vagabond days were over. As a final farewell to the joys of travel, they bought a motor-cycle combination and toured Germany, France, England and Ireland before finally settling down in London. Jan became the art critic of the ‘Observer’ and contributed a series of articles to ‘Colour’ and ‘The Artist’ magazines, which were later developed into a best-selling textbook, 'A Step Ladder to Painting.

...and then I found there was......

A Biographers problem.

A Biographer’s Problem

Jan Gordon was a prolific writer and diarist. Most of his work contained anecdotal biographical references. Easy-peasy for the biographer one would think … Job done.

Tragically however, at the death of Cora in 1950, all their records, letters, notes, photographs, manuscripts seem to have been dispersed or destroyed. The Great Gordon-Give-Away was how it was described to me by one person who had, on being belatedly told of the death of Cora, visited their flat where it appears the friends and relatives of Cora had been invited to help themselves to mementos to take away.

What happened to it all is unclear. A huge amount of artwork remained, some of which I have traced, but apart from the collection of musical instruments given to the Horniman Museum and which are mouldering distressed, unloved and ignored in a storage facility, all has vanished without trace.

I can only mourn the loss of their diaries, manuscripts of several unfinished or unpublished novels, records of their writings, Jan’s photographic records, Cora’s lecture notes, the collection of colour slides, hand coloured by Jan and Cora themselves, with which they used to illustrate their lectures on tours around the UK.

Where, for instance, is the near full size portrait of Cora, painted at the time of their engagement, exhibited at the Paris Salon and still in Clanricarde Gardens at her death? All gone.

All gone except for two diaries dating from 1917 and 1918. So generously gifted to me by Jan’s nephew, the late Micheal Yapp, then living in Jamaica, these diaries had been salvaged by him from the turmoil of the Clanricarde Gardens clearance after Cora Gordon’s death in July 1950, and they have been of immense value in providing a treasure trove of little pieces of confirmatory evidence. Two mismatched and non sequential volumes, tight packed with Jan’s minute, barely legible writing, they took many weeks of patient transcribing with the aid of a magnifying glass.

In the very first pages of one is written: ‘We found Yeats’1 place with difficulty … Ezra Pound came in ... a man was introduced to us as Dulac ...’

As can be imagined my hand was trembling with excitement. Was this to be a discovery packed with literary interest and revelations of icons of those days?

Sadly not, for this volume deals mostly with part of Jan Gordon’s time as a munitions worker at Rolls Royce in Derby and much of it is taken up with descriptions of the tedium of factory work. While working at Roll Royce, every other weekend Jan was able to escape back to London for a reunion with Cora, and to immerse himself in their circle of friends – hence the fleeting mentions of the literati.

Thus by cross references gleaned from Gordon writings and a few surviving acquaintances of Jan and Cora I have been able to gather a number of leads and confirm a number of later anecdotes as fact, enabling me to construct this jigsaw of a biography.

Jan and Cora Gordon lived in an era that reached from the end of fin de siècle Paris, through the Crazy Years of the 1920s to the start of the depressed 1930s with all the innovations and excitement of a world whose ideas, morals and expectations were being utterly transformed. Yet Jan and Cora, although well known in Montparnasse artistic and literary circles, did not partake of the indulgences of those years.

Sweethearts who were seldom parted, they worked steadily and assiduously from their Paris studio.

Rare amongst the stories of inter-war Parisian artistic life there are no stories in this biography of drunken nights nor orgies of booze and drugs; no sexual deviances, no scandals of any kind are left with which their biographer might titillate his readers.

What is left is a story of an inherently decent couple, who lived for their art, who achieved no small degree of fame in both their fields of writing and art, yet because of the events of the time became overlooked and then forgotten save by a few surviving friends, who invariably smile as they say "Ah yes! Jan and Cora" when remembering them. My aim and hope is that I am going some way to ensure that a record of this quite remarkable pair is preserved for future discoverers of them who, after reading one or more of their books are moved to say, ‘I wonder who they were?’

Jan's writing career started with a weekly column in the New Witness, a weekly paper run by Cecil Chesterton, younger brother of GK Chesterton. At some point the Chestertons had had a legal challenge, which they lost, from someone who had claimed that a character in Cecil Chesterton's writing had slandered him, and he was thus awarded some substantial costs. (Hence I suppose the modern disclaimer in novels that ‘… no resemblance …’ etc.)

The fear of being sued must have weighed heavily on Jan and Cora with their limited finances and I can only draw the conclusion that this was the cause of the peculiar choice of somewhat absurd and obscure names or initials that Jan used for the characters in his writing throughout most of his life, a habit that has been the bane of my research. Only by constant cross checking and back referencing, combined with those two so very valuable diaries, have I been able to confirm and decode the fanciful nomenclature he used. It is bad enough that Jan had a peculiar quirk of memory for proper names; ~( Jan Gordon later admitted in a letter to the times that he had all his life suffered from a quirk of memory in regards to proper names and places; Cora spoke amusedly of this when she described how Jan went off to the wrong, publisher for their first book~) Actual places can be looked up in an Atlas, but bizarre invented names are an absolute dead end.

The 1927 novel The Girl in the Art Class is a thinly disguised biography of Cora Gordon. Would that all the bizarre characters chronicled in it had been given their proper names – what a valuable record of Parisian life in the Edwardian era this would be! A few characters are so thinly disguised that they can with a little research, throw up plausible candidates, though not with 100 per cent certainty

This trend continued through Two Vagabonds in Languedoc and the three detective novels, but by the time of Three Lands on Three Wheels in 1932 he had abandoned the bizarre names for an initial followed by a dash (A–) which is still infuriatingly obscure and for the most part the identity can only be a matter of conjecture.

But some examples that I have decoded are given below:-

in 'The Girl in the Art Class' novel cum biography

Raymonde Carpenter = Cora Turner

William Arnold = Jan Gordon

Gruke = Christian Krogh

Issor Calo = Académie Colarossi, Rue de la Grande Chaumière

Marietta’s restaurant = Chez Rosalie, a famous little restaurant 3 rue Campagne Première

Café des Roses = Closerie des Lilas

Rue Villegature Segonde = 9 rue Campagne Première.

Lecontes cremerie = Leducs, 212 Boulevard Raspail

Edals school = Slade school of Art.

One can see the form of some kind of logic emerge;

Carpenter-Turner both wood trades related.

Arnold – Gordon both dual fore-/surnames of Scots origin

Edals – Slade & Issor Calo – Colarossi are simple inversions.

The really pertinent parts, such as Jan’s description of their courtship and engagement, have been confirmed by entries in his diary, such as the entry where Cora expresses the desire to write a novel, and Jan suggests she start at the point where she left home after her ‘father tried to throttle her’. This incident, so pivotal in Cora’s move away from home, is unknown in the family and so melodramatic I would not have included it had I not primary evidence. Like wise the same incident is referred to in Gradus ad Montparnassum, which is littered with small remarks I have found to be factual, such as the small honeymoon art exhibition in Buxton, and the exhibition in Gent, Belgium.

Jan’s diary also records that he ‘… fled to Paris from Gelli …’ Gellibrand being the girl he refers to as Phyllis in The Girl in the Art Class. I believe this girl to be one Margaret Gellibrand .

**Margeret Gellibrand, some lady; born Margeret Adeh Noel Nadejola she married Captain Hastings-Barbour [died 1926] after his war service he joined the Diplomatic Corps in Warsaw Poland. Margeret or Gelli as Nada Patcevitch or Ruffer depending on who she was wed to at the time, went on to become fashion editor of British Vogue magazine 1933-1948 and married the head of Conde Naste. who she divorced 1942. It seems Jan Gordon had a lucky escape.

I believe the most likely candidate for the girl Annette is Nina Hamnett but I can find no definite proof of this even though a photo of Jan Gordon and Nina Hamnett taken with others at the Brangwyn school is in existence.

Similarly there are so many other disguised names at whose real identity I can only guess, and little would be added to this biography if I did … although it is a diverting sideline of inquiry and it would be nice to know the names of those artists and other characters who the Gordons knew in Montparnasse era of 1910. Such minor facts may have made this obscure little book a valuable reference resource for the researcher as so many may well have gone on to become well known artists.

Jan did himself no favours with this disguising of names; also there is his odd memory quirk ,which he confessed to in the mid 1930s, of mis-remembering proper names and their spelling, it would seem he had some kind of dyslexia for such things.( In 1935, in a letter to the Guardian newspaper he confessed this trait of "mis-remembering names" had been with him all his life)

An article from the New Witness 1916 is the first occasion where we see this reticence in recording the real names of people, which reinforces my instinct that it relates to the influence of the Chestertons’ experience. It is titled At the Café des Roses, which is the thinly disguised Closerie des Lilas and one can identify Paul Fort2 and possibly André Salmon3, two literary figures of the era. The futurist painter Marinetti is also identifiable, but whole lists of others are but an initial and a dash. So once again Jan’s reticence or shyness leaves us without a valuable record of the minor (and sometimes quite major) personages of that era.

Tragic then, that while I can identify the Rue du Gaite oyster restaurant mentioned in passing I have few clues as to the identities of the rest of the personalities. In the opening chapter of Three Lands on Three wheels Jan alludes to those Tuesday night gatherings held by Paul Fort at the Closerie des Lilas at the eastern end of the Boulevard Montparnasse, which were quite the in place to be at that time:

‘… where before the War we used to make merry on Tuesday nights with Paul Fort, André Salmon, Picasso and all the lights and lesser lights of the Modern Art Movement …’

Many of the revels, rowdy debates and other events that took place there have been well documented by the mostly French recorders of that era, but sadly no mention of Jan and Cora has been uncovered. Undoubtedly Jan had somewhat boosted the importance of their own presence; would that he had elaborated on some of the others he met there, though perhaps he did in those tragically lost diaries.

In the book Two Vagabonds in Languedoc there are the following examples which mostly follow a transposing of letters method, so we have:

Janac = Najac

Sestrol=Tressol

Dr Saggebou = Boussaguet

Mouly=Marty

And there are several others besides. Mostly these characters can be readily identified due to the respect with which the book is viewed in the village of Najac, and the records and memories to be found there.

Most of the articles that Jan wrote for Blackwoods, Chambers and other journals of that period contain disguised biographical references. The foremost device amongst these is to refer to himself and Cora as William and Mary, and in others Cora becomes Claribel of all things, and I can’t work that one out!

The pattern shows up again in the novel Beans Spilt in Spain which utilises several anecdotes from earlier writing, but it reaches a peak of ridiculous silliness with proper names in his 1930s detective novels, (e.g. Boostin=Austin) which is a great shame as they are really quite a good set of yarns, and they were in fact quite well received by other 1930s crime writers, such as Dorothy l Sayers, and reviewers. Peter Cheney was one of Jan and Coras cocktail party guests at Clanricarde Gardens

My obsessive collecting and re-reading of these writings has shown me that as time progressed Jan in his later books would often refer back to or repeat anecdotes as personal experience. Thus I have drawn strongly on the tale ‘An Experiment in Adventure’ (Blackwoods Magazine) as the story of Jan’s time in Malaysia because the tale appears in précis in A London Roundabout, in the chapter ‘Autobiography from a Loft’.

Some of the anecdotes in that book crop up in The Girl in the Art Class and several more from such sources as A Stepladder to Painting and Beans Spilt in Spain. Stories in the inter war Oxford series of children’s books reveal nuggets about Jan and Cora that cross reference to other items sufficiently to convince me that I have assembled as much as possible that is as near to the fact as possible, given the lack of first hand witness material that I have had to deal with.

Thus I have no hesitation in including large lumps of Jan’s writing as biographical fact once I have established to my own satisfaction that I can find at least one passing back reference to an incident.

In the years I have toiled to assemble this biography I have long struggled with a skeleton of accumulated knowledge while acutely aware that I had no flesh to put on its bones, until it dawned on me that actually I could in effect allow Jan to write his own post-obit biography. So what you are about to read must be viewed as a canvas with a jigsaw laid upon it, a part finished jigsaw, with several pieces lying haphazard as I am not yet sure where they fit. There will be annoying gaps where some pieces have been lost; possibly one or two may not even belong to this puzzle. I have above all tried to ensure that the colour of Jan and Cora comes through with the correct tonal values. Upon that Jan would insist!

Jan Gordon was an avid reader of detective fiction, which was at its heyday between the two world wars and which he would read for relaxation from his more cerebral work. He scattered his writing with a multitude of those small clues which I have followed over the last 30+ years. I like to fantasise that he did it deliberately, though I know he could not have foreseen that some 35 years later one of his readers would be so enamoured of his books that he would be compelled to sit down one evening with an out of date Michelin map of France and a ruler in order to discover the real identity of that small village in France that Jan called Janac, and the subsequent course of events that has led to this point.

In odd reflective moments and in a fanciful mode I like to visualise the two of them looking down at me with a Gordonian chuckle while I have pursued my own Vagabond Journey chasing them.

1 Jack Yeats 1871-1957 not WB Yeates

2 1872- 1960 The “Prince of Poets”, founder, editor of the literary magazine Vers et Prose, the success of which can be gauged by the fact that he used unsold back numbers as furniture in his apartment! Nevertheless he is regarded as an important figure in French literary history

3 1881-1969 André Salmon, poet art critic and writer, became the foremost and most highly respected historian of artistic Paris of the early 20th C.

One day in 1979 I entered a small second-hand book shop in Crystal Palace, South London. It was a small decrepit and old fashioned kind of shop the like of which is probably now extinct. The erudite owner was a lean bespectacled chap with a stereotypical curly collar. Apart from books his stock seemed to be the overflow of his hobbies, fossils and military badges. I was a regular caller at the shop searching for interesting travel books. Never having had the wherewithal to travel I was an avid armchair traveler and had previously found items of interest here.

On this particular day my attention was caught by two books, fittingly tucked up together, for they were by the same co-authors. I paid my £1.25p or 25 shillings, for one of them,as the curly collared proprietor persisted in the dual pricing of all his stock, even though this was some years after the tragedy of decimalisation had hit us.

The title of that book was Two Vagabonds in Languedoc, the authors Jan and Cora Gordon. The book had that nice comfortable appeal that certain books have; cloth-bound with a distinctive binding, the pages thick, hand cut, with a square block of solid old fashioned type set squarely on each wide margined page. Scattered throughout the book were illustrations by the authors.

I was immediately enamoured of the book and its prose… old fashioned, eccentric but elegant and with an understated gentle humour.

It was a friendly book which felt good in my hand. What better reason to buy any book?

I read parts of it aloud to my wife that evening. We were passing through a stressful phase in our lives and we both found this habit relaxing. She too was immediately enchanted, and when I told her of its shelf companion I had left behind she urged me to return and grab it. So the next day another 25 shillings was spent and Poor Folk in Spain was reunited with its sister book.

This addition merely served to whet our appetite for more knowledge about the authors. It’s no exaggeration to say that I was smitten by these two books; a deeper impression was made on my soul than by any other books I had read. Such was the immediate hold of these books I was avid for more information about the authors; I worked out that there was a slight possibility that they may even have still been alive.

This was all the more curious as never before had I felt this compunction; a book read was a book read, and I had enjoyed it or not, to varying degrees. With the better received books I would have sought others from the same author perhaps; maybe thought, “Yes. I would like one day to visit that spot”, but never had I felt such a compulsion on to make a physical connection with the writers.

A small panel in the front of ‘Two Vagabonds’ spoke of a number of other books by the same authors. I drew a blank at the curly collar book shop but a visit to Bromley Central Library produced the British Library list and a whole list of Jan and Cora books. A search began and via several book sellers only a short time elapsed before a dozen titles describing their travels from Lapland to Spain, from Portugal to Albania and the USA were safely housed on my shelves.

The obsession was only fueled further … who where this couple? What happened to them? Were they still alive? The only mention I could find at first was in entries in the library copy of ‘Who Was Who’, and inked in were the notes … died 1944 … died 1950.

So that was that then. No chance that I could ever speak to either.

But maybe they had had children, they would know more.

I reasoned that the best place to start looking for a dead person was at the point of their last recording, in this life anyway, and a little grubbing about in the mêlées of the Public Records births deaths and marriages office and St Catherine House brought forth some terse facts and names; then the ever useful local library gave up their obituary notices. Thus I had a brief outline of where they lived, what they did and when but little else.

So I made a pilgrimage to Clanricarde Gardens in Notting Hill, their last home where they lived from 1932 to the end of their lives, and thence to the crematorium where their travels finally ended.

I must confess I had a lump in my throat as I sat in the garden of remembrance. I felt that I had grown close to this remarkable couple through their books and it seemed just too anticlimactic an event; too unfinished a quest.

So I sat for a while looking at the kaleidoscope of crocus blossoms that carpet the memorial lawn where their ashes are scattered; a field of impressionistic colour quite fitting as the last resting place for two artists.

“Well, I thought, that’s it” and returned home.

But maybe the ashes of Jan and Cora that fed those crocuses provided a little pollen to encourage the flowering of my thoughts. For, far from being at the end I was at the beginning, it was merely the starting point of a quest that is still blooming.

and then on my the way home I thought……” I wonder where their paintings are?”

The Seeds of Obsession had germinated........

Standing amongst the crocuses in the Spring of 1980, at Golders Green crematorium where the ashes of Jan and Cora Gordon had been scattered some 30 years previously, I honestly thought I had reached the end of my quest for this remarkable couple. In fact it was the beginning of a lifetime’s endeavour.

Since I had picked up the copies of 'Two Vagabonds in Languedoc' and 'Poor Folk in Spain' in 1979 I had become enchanted by these two books. As an avid armchair traveler I would devour any travel book I could find, but no author had caught my imagination as these did, so I energetically and often expensively sought out their other titles.

This developed into a true obsession where all was grist to my mill. I sought out lost and misplaced art work, tracked down relatives and generally hounded anyone with living recall about them. Nothing was safe, so that now my coffee cup rests on a tile from the fireplace of their last home in Notting Hill, near to the brass door number of their flat.

The more I found out about them the more I mourned what has been lost.

Jan kept diaries from his early days and carried a camera everywhere with him.

All is lost.

Only two fragmentary diaries survive from the 1917–18 era, gifted to me by his nephew the late Michael Yapp then living in Jamaica.

Their collection of musical instruments, including those so often mentioned in their books and which accompanied them on their travels, lie jealously guarded yet mouldering unloved, in the barn of a warehouse annexe of the South London museum to which they were entrusted.

Yet some several hundreds of their paintings survive: some in the Wellcome Institute; some in the Imperial War Museum; a scattering in various provincial galleries; many in the keeping of friends and relatives, every one of whom has nothing but fond memories of them. Invariably a smile will cross their faces as they recall ‘Aah, yes . . . Jan and Cora . . .’

So, who were they?

Born the son of a parson in 1882 Godfrey Jervis Gordon was educated at Marlborough College, Wiltshire, in keeping with its status as a college for the sons of clergy. His father was a scion of a wealthy Midlands family, his grandfather a one-time Mayor of Litchfield, but by the time Jan was born this wealth had become so very thinly spread amongst the huge extended family, all living off inherited capital, that Jan, as he had become known at college, was having to establish himself in a career. Influenced by his family’s connections he mistakenly elected to become a mining engineer, seduced as he says ‘by the sweet logic of mechanisms . . .’

Cora Josephine Turner, later known always as Jo, had been born three years earlier in Buxton, Derbyshire, the youngest daughter of the locally noted Frederic Turner, himself the son of Samuel Turner to whom a monument still stands in Buxton.

Dr Frederic Turner was a stereotypical Victorian father, a GP, JP and workhouse guardian, who was much-loved by his patients yet who ruled his home with a rod of iron. Despite his display of temper in the face of Cora’s refusal to be bullied into becoming an unpaid nurse, nannie and housekeeper to her Fathers new children by his second wife,and so ending her days as a spinster of the parish, he finally agreed to her going to the Slade School of Art to study the subject for which she had already shown such talent.

While Cora was studying at the Slade School of Art, Jan had unenthusiastically embarked on a doomed bid to make a fortune mining tin in the Malay, his limited enthusiasm further dampened by his disquiet at the way the industry was run and his distaste at the exploitation of the local labour force. Nor did he endear himself to his employer when he was found sketching the fire that burnt down the mine buildings instead of endeavouring to save them.

A small legacy from one of his many maiden aunts enabled him to return to London and study for a while under Frank Brangwyn at the Kensington School of Art. Fate and events conspired to send both Jan and Cora independently to Paris.

Thus 1906-07 found them both separately cast adrift on the shores of Montparnasse, at that time just beginning to oust Montmartre as the artists’ chosen refuge. A growing but somewhat introspective Anglo-Saxon community centred around the many cheap studios and academies brought them together.

Glimpses of their life before 1914 were few and far between at first but a widening circle of contacts has revealed some interesting information, of which more later.

They lived in and around the very hub of Montparnasse; they once took a studio in the very building that had recently housed Alphonse Mucha; they frequented the Closerie des Lilas, where they met with Picasso and ‘ . . .all the leading and lesser lights of the modern art movement . . .’ Did they ever trip over Modigliani lying drunk somewhere; did they regard him as a drunken nuisance or would they have spent a few francs on one of his sketches in the Dôme café? Did they share a table with the young Hemingway? Did Joyce sponge off them? Were they ever admitted to Gertrude Stein’s sanctum? They would have known of her and her art interests through Nina Hamnett, with whom Jan studied and of whom he was quite fond.

What of all the other characters and artists who used the Carrefour Vavin as their rendezvous? Jan initially lived in a hotel in the street behind the Cafe du Dôme and painted in the Luxembourg gardens, while Cora was a regular student at Colarossi’s academy in the Rue de la Grande Chaumière. Did Cora meet up with Arthur Ransome, who lived in the same block of studios at 9 Rue Campagne Premiere? She certainly knew him as a girl and he may have been the subject of her first girlish love. All such tantalising possibilities remain unknown, the meat I have long striven to put upon the bones of what I have been able to discover about their early life in Paris.

It was the 1914-18 war that stunted their nascent artistic career, yet kick-started their literary career. They had begun to be noticed for their art when the war intervened. Jan was classed as unfit for military service but volunteered for service with the Red Cross in Serbia - how and with whom makes an amusing story of its own (see 'Jan and Cora in Serbia 1914-15' on this site).

On their return to London after the hardships and adventures alluded to above, Jan and Jo were sorely in need of some income and wrote about their adventures in the Westminster Gazette, which in turn led to a commission to write ' The Luck of Thirteen' followed by 'A Balkan Freebooter', a transcript of a Balkan adventurer’s life story.

Jan, who by then had been ‘directed’ into war work, spent 18 months making aeroplane engine parts at Rolls Royce, Derby, but still managed to write numerous articles about art for New Age, New Witness, Nation, Country Life and others. He then went on to work on dazzle camouflage schemes for ships at the Royal Academy, for which he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve.

1919.......

As soon as they were able, funded by Jan’s war gratuity and what he received as official war artist for the Navy Medical Section, they returned to Paris and thence to Spain. Jan had conceived a passion for the Spanish guitar during the war and was determined to sample the music of this instrument at source, along with Jo, who was an accomplished player of violin and piano, having studied at the Manchester Conservatory of Music.

The foundations of their unmistakable writing style were laid in Spain with their two books 'Poor Folk in Spain' and 'Misadventures With a Donkey'. No guide book plagiarism here, no ruins, no church entrails, no socialising with expatriates; Jan and Jo recorded everyday life and trivia and the characters they met with humour, neither condescending nor patronising, though one must sometimes remember that certain flavours of Jan’s phraseology that these days would be considered non-PC are but a reflection of the education and attitudes of an England now a century past. Both these books are as highly regarded in Spain for their observations of ordinary daily life and customs contained therein, as is the Languedoc book in Najac. ‘Poor Folk’ is used to this day to illustrate the complexities and pitfalls of older English grammar and usage in the English department at Murcia University.

At the end of the war, a small service gratuity enabled them to return to their Paris studio. It was now that they decided to combine their literary and artistic skills to research, write and illustrate their first travel book, 'Poor Folk in Spain', published in 1922. The following year, they returned to Spain, this time trekking across the southern half of the country with a donkey and cart. 'Misadventures With A Donkey in Spain' was very well received by the critics, with several reviewers comparing it favourably with Stevenson’s Travels with a Donkey. Hard on the heels of this success came publication of 'Two Vagabonds in Languedoc'. 1925

The Twenties proved to be a bountiful era for the Gordons. Their travel books helped fund Jan’s novels, 'Buddock against London' and 'Girl in the Art Class', a thinly disguised biography of Cora, 'Beans spilt in Spain', a novel largely inspired by events they had not recorded in their Spanish books, and his critical reputation was further enhanced by the publication of 'Modern French Painters' in 1922. Meanwhile, their wanderings took them to Sweden in 1924, Albania in 1925 and Portugal in 1926.

Their growing reputation in the USA led to a grand tour there in 1927-28 but Jan suffered a heart-attack halfway through and on return to Europe they decided that their vagabond days were over. As a final farewell to the joys of travel, they bought a motor-cycle combination and toured Germany, France, England and Ireland before finally settling down in London. Jan became the art critic of the ‘Observer’ and contributed a series of articles to ‘Colour’ and ‘The Artist’ magazines, which were later developed into a best-selling textbook, 'A Step Ladder to Painting.

...and then I found there was......

A Biographers problem.

A Biographer’s Problem

Jan Gordon was a prolific writer and diarist. Most of his work contained anecdotal biographical references. Easy-peasy for the biographer one would think … Job done.

Tragically however, at the death of Cora in 1950, all their records, letters, notes, photographs, manuscripts seem to have been dispersed or destroyed. The Great Gordon-Give-Away was how it was described to me by one person who had, on being belatedly told of the death of Cora, visited their flat where it appears the friends and relatives of Cora had been invited to help themselves to mementos to take away.

What happened to it all is unclear. A huge amount of artwork remained, some of which I have traced, but apart from the collection of musical instruments given to the Horniman Museum and which are mouldering distressed, unloved and ignored in a storage facility, all has vanished without trace.

I can only mourn the loss of their diaries, manuscripts of several unfinished or unpublished novels, records of their writings, Jan’s photographic records, Cora’s lecture notes, the collection of colour slides, hand coloured by Jan and Cora themselves, with which they used to illustrate their lectures on tours around the UK.

Where, for instance, is the near full size portrait of Cora, painted at the time of their engagement, exhibited at the Paris Salon and still in Clanricarde Gardens at her death? All gone.

All gone except for two diaries dating from 1917 and 1918. So generously gifted to me by Jan’s nephew, the late Micheal Yapp, then living in Jamaica, these diaries had been salvaged by him from the turmoil of the Clanricarde Gardens clearance after Cora Gordon’s death in July 1950, and they have been of immense value in providing a treasure trove of little pieces of confirmatory evidence. Two mismatched and non sequential volumes, tight packed with Jan’s minute, barely legible writing, they took many weeks of patient transcribing with the aid of a magnifying glass.

In the very first pages of one is written: ‘We found Yeats’1 place with difficulty … Ezra Pound came in ... a man was introduced to us as Dulac ...’

As can be imagined my hand was trembling with excitement. Was this to be a discovery packed with literary interest and revelations of icons of those days?

Sadly not, for this volume deals mostly with part of Jan Gordon’s time as a munitions worker at Rolls Royce in Derby and much of it is taken up with descriptions of the tedium of factory work. While working at Roll Royce, every other weekend Jan was able to escape back to London for a reunion with Cora, and to immerse himself in their circle of friends – hence the fleeting mentions of the literati.

Thus by cross references gleaned from Gordon writings and a few surviving acquaintances of Jan and Cora I have been able to gather a number of leads and confirm a number of later anecdotes as fact, enabling me to construct this jigsaw of a biography.

Jan and Cora Gordon lived in an era that reached from the end of fin de siècle Paris, through the Crazy Years of the 1920s to the start of the depressed 1930s with all the innovations and excitement of a world whose ideas, morals and expectations were being utterly transformed. Yet Jan and Cora, although well known in Montparnasse artistic and literary circles, did not partake of the indulgences of those years.

Sweethearts who were seldom parted, they worked steadily and assiduously from their Paris studio.

Rare amongst the stories of inter-war Parisian artistic life there are no stories in this biography of drunken nights nor orgies of booze and drugs; no sexual deviances, no scandals of any kind are left with which their biographer might titillate his readers.

What is left is a story of an inherently decent couple, who lived for their art, who achieved no small degree of fame in both their fields of writing and art, yet because of the events of the time became overlooked and then forgotten save by a few surviving friends, who invariably smile as they say "Ah yes! Jan and Cora" when remembering them. My aim and hope is that I am going some way to ensure that a record of this quite remarkable pair is preserved for future discoverers of them who, after reading one or more of their books are moved to say, ‘I wonder who they were?’

Jan's writing career started with a weekly column in the New Witness, a weekly paper run by Cecil Chesterton, younger brother of GK Chesterton. At some point the Chestertons had had a legal challenge, which they lost, from someone who had claimed that a character in Cecil Chesterton's writing had slandered him, and he was thus awarded some substantial costs. (Hence I suppose the modern disclaimer in novels that ‘… no resemblance …’ etc.)

The fear of being sued must have weighed heavily on Jan and Cora with their limited finances and I can only draw the conclusion that this was the cause of the peculiar choice of somewhat absurd and obscure names or initials that Jan used for the characters in his writing throughout most of his life, a habit that has been the bane of my research. Only by constant cross checking and back referencing, combined with those two so very valuable diaries, have I been able to confirm and decode the fanciful nomenclature he used. It is bad enough that Jan had a peculiar quirk of memory for proper names; ~( Jan Gordon later admitted in a letter to the times that he had all his life suffered from a quirk of memory in regards to proper names and places; Cora spoke amusedly of this when she described how Jan went off to the wrong, publisher for their first book~) Actual places can be looked up in an Atlas, but bizarre invented names are an absolute dead end.

The 1927 novel The Girl in the Art Class is a thinly disguised biography of Cora Gordon. Would that all the bizarre characters chronicled in it had been given their proper names – what a valuable record of Parisian life in the Edwardian era this would be! A few characters are so thinly disguised that they can with a little research, throw up plausible candidates, though not with 100 per cent certainty

This trend continued through Two Vagabonds in Languedoc and the three detective novels, but by the time of Three Lands on Three Wheels in 1932 he had abandoned the bizarre names for an initial followed by a dash (A–) which is still infuriatingly obscure and for the most part the identity can only be a matter of conjecture.

But some examples that I have decoded are given below:-

in 'The Girl in the Art Class' novel cum biography

Raymonde Carpenter = Cora Turner

William Arnold = Jan Gordon

Gruke = Christian Krogh

Issor Calo = Académie Colarossi, Rue de la Grande Chaumière

Marietta’s restaurant = Chez Rosalie, a famous little restaurant 3 rue Campagne Première

Café des Roses = Closerie des Lilas

Rue Villegature Segonde = 9 rue Campagne Première.

Lecontes cremerie = Leducs, 212 Boulevard Raspail

Edals school = Slade school of Art.

One can see the form of some kind of logic emerge;

Carpenter-Turner both wood trades related.

Arnold – Gordon both dual fore-/surnames of Scots origin

Edals – Slade & Issor Calo – Colarossi are simple inversions.

The really pertinent parts, such as Jan’s description of their courtship and engagement, have been confirmed by entries in his diary, such as the entry where Cora expresses the desire to write a novel, and Jan suggests she start at the point where she left home after her ‘father tried to throttle her’. This incident, so pivotal in Cora’s move away from home, is unknown in the family and so melodramatic I would not have included it had I not primary evidence. Like wise the same incident is referred to in Gradus ad Montparnassum, which is littered with small remarks I have found to be factual, such as the small honeymoon art exhibition in Buxton, and the exhibition in Gent, Belgium.

Jan’s diary also records that he ‘… fled to Paris from Gelli …’ Gellibrand being the girl he refers to as Phyllis in The Girl in the Art Class. I believe this girl to be one Margaret Gellibrand .

**Margeret Gellibrand, some lady; born Margeret Adeh Noel Nadejola she married Captain Hastings-Barbour [died 1926] after his war service he joined the Diplomatic Corps in Warsaw Poland. Margeret or Gelli as Nada Patcevitch or Ruffer depending on who she was wed to at the time, went on to become fashion editor of British Vogue magazine 1933-1948 and married the head of Conde Naste. who she divorced 1942. It seems Jan Gordon had a lucky escape.

I believe the most likely candidate for the girl Annette is Nina Hamnett but I can find no definite proof of this even though a photo of Jan Gordon and Nina Hamnett taken with others at the Brangwyn school is in existence.

Similarly there are so many other disguised names at whose real identity I can only guess, and little would be added to this biography if I did … although it is a diverting sideline of inquiry and it would be nice to know the names of those artists and other characters who the Gordons knew in Montparnasse era of 1910. Such minor facts may have made this obscure little book a valuable reference resource for the researcher as so many may well have gone on to become well known artists.

Jan did himself no favours with this disguising of names; also there is his odd memory quirk ,which he confessed to in the mid 1930s, of mis-remembering proper names and their spelling, it would seem he had some kind of dyslexia for such things.( In 1935, in a letter to the Guardian newspaper he confessed this trait of "mis-remembering names" had been with him all his life)

An article from the New Witness 1916 is the first occasion where we see this reticence in recording the real names of people, which reinforces my instinct that it relates to the influence of the Chestertons’ experience. It is titled At the Café des Roses, which is the thinly disguised Closerie des Lilas and one can identify Paul Fort2 and possibly André Salmon3, two literary figures of the era. The futurist painter Marinetti is also identifiable, but whole lists of others are but an initial and a dash. So once again Jan’s reticence or shyness leaves us without a valuable record of the minor (and sometimes quite major) personages of that era.

Tragic then, that while I can identify the Rue du Gaite oyster restaurant mentioned in passing I have few clues as to the identities of the rest of the personalities. In the opening chapter of Three Lands on Three wheels Jan alludes to those Tuesday night gatherings held by Paul Fort at the Closerie des Lilas at the eastern end of the Boulevard Montparnasse, which were quite the in place to be at that time:

‘… where before the War we used to make merry on Tuesday nights with Paul Fort, André Salmon, Picasso and all the lights and lesser lights of the Modern Art Movement …’

Many of the revels, rowdy debates and other events that took place there have been well documented by the mostly French recorders of that era, but sadly no mention of Jan and Cora has been uncovered. Undoubtedly Jan had somewhat boosted the importance of their own presence; would that he had elaborated on some of the others he met there, though perhaps he did in those tragically lost diaries.

In the book Two Vagabonds in Languedoc there are the following examples which mostly follow a transposing of letters method, so we have:

Janac = Najac

Sestrol=Tressol

Dr Saggebou = Boussaguet

Mouly=Marty

And there are several others besides. Mostly these characters can be readily identified due to the respect with which the book is viewed in the village of Najac, and the records and memories to be found there.

Most of the articles that Jan wrote for Blackwoods, Chambers and other journals of that period contain disguised biographical references. The foremost device amongst these is to refer to himself and Cora as William and Mary, and in others Cora becomes Claribel of all things, and I can’t work that one out!

The pattern shows up again in the novel Beans Spilt in Spain which utilises several anecdotes from earlier writing, but it reaches a peak of ridiculous silliness with proper names in his 1930s detective novels, (e.g. Boostin=Austin) which is a great shame as they are really quite a good set of yarns, and they were in fact quite well received by other 1930s crime writers, such as Dorothy l Sayers, and reviewers. Peter Cheney was one of Jan and Coras cocktail party guests at Clanricarde Gardens

My obsessive collecting and re-reading of these writings has shown me that as time progressed Jan in his later books would often refer back to or repeat anecdotes as personal experience. Thus I have drawn strongly on the tale ‘An Experiment in Adventure’ (Blackwoods Magazine) as the story of Jan’s time in Malaysia because the tale appears in précis in A London Roundabout, in the chapter ‘Autobiography from a Loft’.

Some of the anecdotes in that book crop up in The Girl in the Art Class and several more from such sources as A Stepladder to Painting and Beans Spilt in Spain. Stories in the inter war Oxford series of children’s books reveal nuggets about Jan and Cora that cross reference to other items sufficiently to convince me that I have assembled as much as possible that is as near to the fact as possible, given the lack of first hand witness material that I have had to deal with.

Thus I have no hesitation in including large lumps of Jan’s writing as biographical fact once I have established to my own satisfaction that I can find at least one passing back reference to an incident.

In the years I have toiled to assemble this biography I have long struggled with a skeleton of accumulated knowledge while acutely aware that I had no flesh to put on its bones, until it dawned on me that actually I could in effect allow Jan to write his own post-obit biography. So what you are about to read must be viewed as a canvas with a jigsaw laid upon it, a part finished jigsaw, with several pieces lying haphazard as I am not yet sure where they fit. There will be annoying gaps where some pieces have been lost; possibly one or two may not even belong to this puzzle. I have above all tried to ensure that the colour of Jan and Cora comes through with the correct tonal values. Upon that Jan would insist!

Jan Gordon was an avid reader of detective fiction, which was at its heyday between the two world wars and which he would read for relaxation from his more cerebral work. He scattered his writing with a multitude of those small clues which I have followed over the last 30+ years. I like to fantasise that he did it deliberately, though I know he could not have foreseen that some 35 years later one of his readers would be so enamoured of his books that he would be compelled to sit down one evening with an out of date Michelin map of France and a ruler in order to discover the real identity of that small village in France that Jan called Janac, and the subsequent course of events that has led to this point.

In odd reflective moments and in a fanciful mode I like to visualise the two of them looking down at me with a Gordonian chuckle while I have pursued my own Vagabond Journey chasing them.

1 Jack Yeats 1871-1957 not WB Yeates

2 1872- 1960 The “Prince of Poets”, founder, editor of the literary magazine Vers et Prose, the success of which can be gauged by the fact that he used unsold back numbers as furniture in his apartment! Nevertheless he is regarded as an important figure in French literary history

3 1881-1969 André Salmon, poet art critic and writer, became the foremost and most highly respected historian of artistic Paris of the early 20th C.

The crocus lawn at Golders Green crematorium, last resting place of Jan and Cora Gordon.

Cora's ashes were scattered to the left, Jan's to the right of this centre path; no memorial plaque but a few crocus left by myself.

They are though, in notable company. Many literary and artistic people have a memorial of some kind in these grounds.

photo copyright Andy Dolman from Wiki.