Jan's childhood home at Woodlands, Dorset

Jan's childhood home at Woodlands, Dorset

Godfrey Jervis Gordon was born in Finchampsted, Berkshire on 11 March 1882. He came into a large and well to do ecclesiastical family. His father Alexander, curate at Finchampsted, and was one of numerous sons of William Francis Gorden, mine owner and businessman of some standing of Lichfield, Staffordshire, JP, workhouse guardian and Mayor of Lichfield 1880-81. W F Gordon had at least four other sons, most of whom were clergy and one doctor” "Expensively educated, partly on capital" was how Jan was to describe them later.

Interestingly it has recently come to light that Jan is a cousin, via his father of the noted artist Phil May(1864-1903); the May family were also mine owners.

In his almost auto-biographical novel " A Girl in the Art Class" he writes " ....my people (are what is called leisured grandfolks on both sides were pretty well off, all my aunts and uncles left with enough money to live off, cultivate hobbies and grow up in sublime ignorance of the world ... "

In keeping with the ecclesiastical theme, Jan's mother also came from an intensely church family. Juliette Blanche Gabrielle was the daughter of the Reverend John Graham, curate of at Chad's, Lichfield. He became prebendary of Lichfield Cathedral and a plaque to the memory of his forty years service at Chad’s is today on the wall of that place of worship

WF Gordon lived opposite to at Chad's in Stowe House, an imposing residence with connections to that other son of Lichfield, Dr Samuel Johnson. It is tempting to speculate if Alexander knew Juliette in childhood. They must (as children of two such church orientated families, have had contact, a marriage made, if not in heaven, then at least quite close!

Clergy in those days were kept on the move. In 1883 the Rev Alexander moved to Wiltshire, to Donhead St Mary, and then in 1887 they were off again to Wyke Regis, Dorset until 1890 and thence to Horton and Woodlands in Dorset.

In this several hundred years old house, with its ancient mulberry tree, Jan was to spend the happiest years of his childhood.

Little else is known about his very early childhood except that at Bournemouth he records was nearly drowned at the age of four. But he evidently had a near idyllic childhood at the rectory at Woodlands. “ this country between Avebury and the Isle of Purbeck was the country of my childhood's driftings".

"Nothing can ever oust the landscapes of our childhood. That collection of images first recorded by our unreflective minds, to which all other images are referred, form the instinctive background of our future world However splendid, in whatever lovely woods we may find them, no glades have quite the magic of the glades through which we first hunted butterflies, counting the yellow fritillary, a noble prize, and one white admiral, enough to spread glamour over whole years of the chase. No mountains for me are quite splendid enough to supplant the memories of the Downs, with their slow breasting magnificence and their serene solitude in the midst of hurry ” …………..

“…the magnitude of these small adventures lingers unrivaled by anything that can come later".

The Gordon family was obviously collectively very fond of that part of England as most of them returned to Dorset (and Wiltshire) for the rest of their lives, His brother Roland Gordon becoming Mayor of Salisbury in 1947-9 .

The Reverend Alexander and Jan's sisters Beatrix and Pearlie now rest in the cemetery at Salisbury.

-------------------------------o--------------------------------

In the closing years of the 19th century a small Jan Gordon stood at a wooded corner near Woodlands, Dorset, impatiently tearing open the package containing his first camera, that he had just collected from the railway station, about a mile and a half from home, a small item costing just some seven shillings and sixpence

“ no future camera, however complete and expensive, has ever given me half the delight of that one ".

In 1893, Jan's happy childhood came to an abrupt end when he was sent to Marlborough College, the clergyman's public school, founded specifically for the sons of clergy some years earlier. Jan loathed his time at this school. He describes himself as the odd boy out. "The persecution of the new boy" he would describe it, in still painful remembrance in 1918.

The Marlborough school records show that in 1893 he was a small lad, four feet nine inches tall, weighing less than six stone, asthmatic and bespectacled, a sensitive child who would always rather read than play tennis or rugby, he was an obvious target for the school bullies.

He describes himself as a dunce until about 13 when "a sudden and unexpected success made way to an astonishing development". This is confirmed by the school records. From a rather poor showing his academic work shot ahead. He was in the engineering class (a respected profession in those days) and by 1898 he had gained a high placing in "end of term orders" and was the form prizes in science, moths and engineering drawing. He had also made an astonishing growth physically, for in 1898, the last record existing, he was approaching six feet in height and 11 stone in weight,

His extra confidence gained from this increase in height and bulk no doubt helped him to a place in the school 2nd Rugby team. I hope he evened things up a bit with his former tormentors.

In March 1899 he left Marlborough vowing to forget the school and all that went on there. It seems that the only return he made to the school was in 1931 when they passed through the area in the tour described in "Three Lands on Three Wheels" and then only ventured as far as the school gates.

Perhaps only the name "Jan" remained with him as a souvenir of those days, for it seems that was the era he acquired that name, which he kept in preference to his baptismal names. There is another possibility that it may have come from Cornwall days later, where it was a common name.

No doubt because of his engineering aptitude and his grandfather's business interests a good deal of whose wealth stemmed from mining, a career in mining was deemed to be suitable for Jan, but firstly he spent time at Royal Indian Engineering College,Coopers Hill ,Egham and later 1901 we find him in respectable lodgings in Belmont Villas , Truro, Cornwall with the family of Francis Hockady, a Butler,according to the 1901 census return, and enrolled at the Truro School of Mines, Cornwall.

He describes his time there as "raising old Harry and at the end of three years putting in the three months necessary grind to come out with 1st class certificates."

Truro school of mines also had classes for the drawing of high quality maps and charts.

I am sure Jan would have made the most of those. There seems to be a strong family attraction to Cornwall, possibly because of the strong mining interest on both sides of Jan's family who appear to have drawn considerable income from mining shares. I have spent a lot of time tracing the half sisters of Cora who all also moved from Scotland to Cornwall, where they married but had no children.

However blasé he may have been about his efforts he passed with 98% of the possible total. He was sure he was a born engineer and writes in "London Roundabout" of his love of drawing and "the sweet logic of mechanisms". He had been told off at Marlborough for "defacing his school books, designing shapes on paper" He had a love of making things with his hands and even later in life would again write that he "preferred the smell of an engine to that of a rose.

But on 4th August 1904 Jan was embarked on the P&O steamer Manila en voyage to Penang Malaysia to manage one of the numerous tin mines in that part of the globe, where earth's bounty was "wrung out of the earth by Chinese coolies for the greater profit of the British Empire". It was to be a traumatic time in the life and future of Jan Gordon.

His reminiscences of that time were related in Blackwoods Magazine May 1923 under the title "An Experiment in Adventure".

He had undertaken a two year contract as under-manager of a tin mine - a disastrous engagement for it transpired he had been lured into a private speculation that rapidly failed. A subsequent attempt in another mine brought only boredom and disillusion with the job. When he passed his final exams at the School of Mines with top marks he had felt sure that he was a born engineer. In practice he found that the depressing reality of life in the field meant he was constantly engaged in an endless habit of make-do and mend, bodging and makeshift repairs which he knew were unsafe and wrong because there was neither money nor resources to do the job properly as he had been taught - a state of affairs with which I feel a strong personal sympathy.

The tedium of managing the Chinese labourers day in, day out, of having to see that the overseers themselves did their job, seeing that the tallymen did not cheat the labourers, bored him. He calculated that his job was 95% watching, seeing that nothing went wrong " -keeping monotony triumphant".

Those things that so drew him to engineering at Marlborough - "a love of drawing, not nature but shapes on paper _ ", " scribbling they called it when he defaced his school books - his love of mechanical problem solving and working with his hands " - the lack of these things began to disillusion him as to his choice of profession.

His only relief from the monotony was an occasional visit to a nearby village three miles away to a Chinese gambling house or theatre in which he found amusement. A certain sympathy with the Chinese labourers also manifested itself. Watching them day in, day out toiling 10 hours a day under the sun, carting loads of earth and ore up 60 foot high ladders. He had neither stomach nor inclination to force them to do what he himself was incapable of doing. Not that this gained him any respect from the workers, for they, being used to harder taskmasters, considered him to be a soft touch.

On one or two occasions he lost his temper and gave ,as he ashamedly wrote, a 'thrashing' to one of the workers, and five minutes later feeling thoroughly ashamed of himself, but he found that because the men concerned could not find rhyme nor reason for the outburst, they resented it all the more. On the other hand one of Jan's management partners seemed to lash out on a regular basis, and the workers seemed to accept these beatings as normal. Jan's inherent sense of fair play would have made him very unhappy in those circumstances.

The torrential rains of the Malay also depressed Jan, especially at night, when the dangerously built mine pits were in danger of mudslides cascading into the mine workings. (Even years later the sound of heavy rain on the studio roof would fill him with oppressive gloom.)

The affair of the dam was to be the end of this job. The owners decided that the mine needed more water, so Jan designed a dam on proper engineering standards, but this was vetoed on the grounds of cost and a traditional Chinese dam of basketwork and earth was used. Once more Jan got the dirty work to do. This time he was tasked with evicting ten Chinese families of market gardeners " - once happy families, made miserable so that one man could become a little richer- ".

Needless to say, under the Chinese manager corners were cut, work skimped.

A week later a torrential downpour burst the dam and swept the valley beneath it, burying flourishing market gardens and ruining hundreds of lives.

Jan had had enough. He broke his contract with that mine and entered into a speculative partnership building roads through the jungle. Unfortunately, other more crafty local speculators had cornered the supply of road building stone and so in a very few months the bottom had fallen out of that enterprise and Jan was looking for yet another job. More or less penniless, Jan was forced into mines again, albeit this time to a mine a little better equipped.

Still the dreadful monotony gnawed at Jan. He got through the day shifts well enough, but the nights he found long and tedious. Sitting in his office under the constant hum of mosquitoes he began to draw in order to pass the time better. He lost himself in his sketchbooks, often spending six hours continuously sketching, losing himself in the task to the extent that once when a fire broke out in the mine he was more concerned with the sketching of it than the extinguishing of it - to the great displeasure of his employers.

Some of these sketches were sent to a local art exhibition in the nearest big town where to his excitement and encouragement he won a prize.

He kept at his drawing for hours at a time, yet his pleasure in the art show prize was to be short lived. One night one of the Chinese workers was killed when the overhanging cliff collapsed.

Though at the ensuing inquiry Jan was cleared, he blamed himself for negligence. Negligence in failing to drive the men as hard as the other managers. He had allowed workers to take short cuts behind his back.

After the affair he came to regard himself as inadequate to the task. He lost confidence in himself and faith in his abilities.

Anticipating a dismal future going from one job to another around the Malay, antagonising one mine owner after another, he had no wish to fall into the same trap as had those

" - unemployables who existed by playing jester in the houses of lonely white men, or by cadging from semi-contemptuous Chinamen".

He considered he would have more self-respect if he failed at something he liked, namely Art, rather than that which he actively disliked. So, probably either late 1906, early 1907, at the age of twenty five, he took the decision to become a full time artist.

Borrowing money for the passage home, he packed his trunk once more and took shop via Ceylon and Aden, a voyage home made more miserable in the cheap cabin next to the cookhouse by a bout of malaria.

The postscript to this is Jan's comments on himself in "London Roundabout" 1933.

"- My certificates, which guaranteed me thoroughly competent and of exceptional quality were complete frauds. Of that quality, most essential for the mining engineer, the capacity to dominate men in the mass, I had hardly a spark. In subsequent years I may have become to some extent captain of my own soul, but nature never designed me to be even lance corporal of someone else's."

"Luck again. I might have become a fairly decent mechanical engineer, but mining I was a complete failure. Yet how lucky it is to realise in time when one is destined for failure. The trunk which took me out to the Malay, in less than two years followed me back to England. Afterwards, covered with a rug, it had to serve as a seat in my first Bohemian lodgings at three shillings a week, in Chelsea."

----------------------------------o------------------------------------------------

Back to London but not for long.

Those lodgings Jan and an unknown friend found were at 133 Cheyne Walk Chelsea; lodgings that even for the standards of the day seem to have been a little less than modest.

A mere three shillings a week got them rooms in the Milton Chambers Artisan Dwellings that included bed bugs and other unwelcome sub tenants.

One luckless parasite was imprisoned in a coral of ‘Sanitas’ disinfectant for some days.

Jan’s unknown friend made good use of the unfortunate insects’ plight by making such detailed studies of it, that he was accepted, on the strength of these studies for a Polar expedition as result of the drawing skills acquired by studying this luckless insect

The major furnishings of the rooms seemed to be Jan’s luggage trunk, serving with a rug throw over as a seat, and a huge yellow vase he had brought back from the Malay.

Jan and his friend enrolled at the London School of Art otherwise known as Brangwyns after the head of studies, Frank Brangwyn RA who Jan described as “...the best art teacher I ever had…”

Certainly in Jan’s early etching work such as that which he that he had accepted for the Paris salon of 1912 showed a heavy Brangwyn influence.

Somehow Jan and his friend found that the latch key to their lodgings also fitted the lock of the door of the art school and they would arrive at 6am in order to gain a four hour extra study advantage over the other students who did not arrive till 10.

Jan applied himself with typical vigour to his studies at Brangwyns, and also to the “Bohemian” life of the Chelsea art set of that era, although apparently not into the decadence that was possible in those quarters.

“…he learned to dance, drank in the Six Bells, dined in the back room of the Worlds End pub, got to know Augustus John by sight, played pranks on the old maids,…” [Who were evidently features of all art schools in the Edwardian era] “…with dogs in the classes, hectored the girls in the tea club and in general had the best kind of life for the student artist…”

Among the other students at Brangwyns was the latter-day art critic RH Wilenski, one Nina Hamnett and a mysterious girl known only from Jan’s diary as “Jellibrand” who was to play a pivotal role in Jan’s life.

Jan formed a long lasting and companionate friendship here with Nina Hamnett, who was an energetic tomboy. The jolly hockey sticks, hearty type of minor public school girl.

“… I remember what a schoolgirl she was at art school...” and with her she seemed to have shared many of his art school pranks; though nothing else it would appear; the those favours she was to shower so liberally and indiscriminately later on were not yet available. Nina was more of a sisterly companion.

Jan seemed to have retained affection for her; she is as reported in his diaries by his references to her, as ‘Ham’

Throughout his career as a critic and writer on matters art Jan never failed to look and remark favourably on Nina’s work, and, although no doubt mortified by her habits and behaviour never failed to boost her work with favourable comments when she exhibited., and by the late 1930s when she had raddled herself with drugs booze and sex she needed all the help she could get.

But Jan’s nemesis at Brangwyns was to be the mysterious Gellibrand, or ‘Jelli’ as she was referred to by Jan,

I believed for many years that she was the notorious Paula Gellibrand, youngest of three daughters, Winifred, Margaret, and Paula of one William Clark Gellibrand, timber merchant, of Drayton Gardens, Chelsea, and a Russian mother which would have made for an interesting bit of research, but the age gaps and dates did not tally.

Paula Gellibrand was the ‘IT’ girl of her time made famous by Cecil Beaton and notorious by her affairs with numbers of high society men.

The Gellibrand girl that was Jan's embarrassment, was, as far as I can be certain, Margaret Gellibrand. In ‘The Girl in the Art Class’ she is referred to as “Phyllis.” While Jan describes Nina (called Annette in GAC) as a comrade. Phyllis (Margaret) was a different kettle of fish altogether and seems to have led on, teased and generally manipulated poor Jan.

**Margeret Gellibrand, some lady; born Margeret Adeh Noel Nadejola she married Captain Hastings-Barbour [died 1926] after his war service he joined the Diplomatic Corps in Warsaw Poland. Margeret or Gelli as Nada Patcevitch or Ruffer depending on who she was wed to at the time, went on to become fashion editor of British Vogue magazine 1933-1948 and married the head of Conde Naste. who she divorced 1942. It seems Jan Gordon had a lucky escape

(She was evidently an enthusiastic ‘prick teaser’, which, a present day member of the Gellibrand family laughingly told me, is a noted characteristic of the Gellibrand girls past and present!)

(

In the novelette/cum biography ‘A Girl in the Art Class’ he tells it thus………

Oh”, he said “I made rather a fool of myself with Phyllis…”

“…It was a revelation to William that there were women other than sisters, who could be treated as sensible human beings, with whom one could call a shovel a bloody shovel if one wished.

The set at Earls Court was gregarious. William was made welcome into it. And then a girl undertook some of his education. It was curious that William had not learned much about women from her.

He believed that he might have done so, for she was gay and lively, as ready for a practical joke as for a flirtation, for a dance as companionship. The platonic was in fashion at the Earls court, for there was on the whole a general frank comradeship which almost repressed the flirtatious element as a nuisance and bad form. Annette had taught William to dance, an accomplishment at which he had always boggled, because it had to be performed in the terrifying embrace of some maiden easy to dishevel with a little clumsiness. But Annette needed a dancing partner; William was the best available material.

Once he had mastered the steps and the rhythm he became enthusiastic for he was musical enough. Then he found that learning to dance had made an improvement in his painting………..”

“……..but after a year Annette was called home and William was transferred to the company of Phyllis, Annette best friend.

The situation was now rapidly altered. With Annette a comradeship had been easy, with Phyllis it was impossible. Annette was bluff easy going, sharing her pleasure with everybody: Phyllis was winsome, reticent, preferred to enjoy a joke all by herself, and had impulses to domination. Annette had been content to be an equal. Phyllis wished to reduce William to a subjects place. So the road to a sly flirtation was opened to him, and from Phyllis who saw that he was dense in such matters, the invitation was made correspondingly clear. In a short while William found himself in the position of a cyclist with inefficient brakes, who having put his feet up for a modest slope sees a steep downhill before him.

Having subjected William Phyllis began to loose interest in him; he was but a scalp; she then looked about for other conquests. William was now something of a nuisance to her, except as a fetcher and carrier. For a while William mooned about with a seedy heart. Then suddenly he became exasperated at himself, packed up his trunk, left a huge yellow jar, his only objet de vertu, with his best friend and bolted to Paris...........

***interestingly the previous occupant of their rue bagneux studio in Paris was a Scottish sculptress named Phyliss, Phyliss Muriel Cowan, and in his diary Jan mentions a fiend of Coras from Buxton called Hilda Cowan. I am tempted to to surmise a connection.

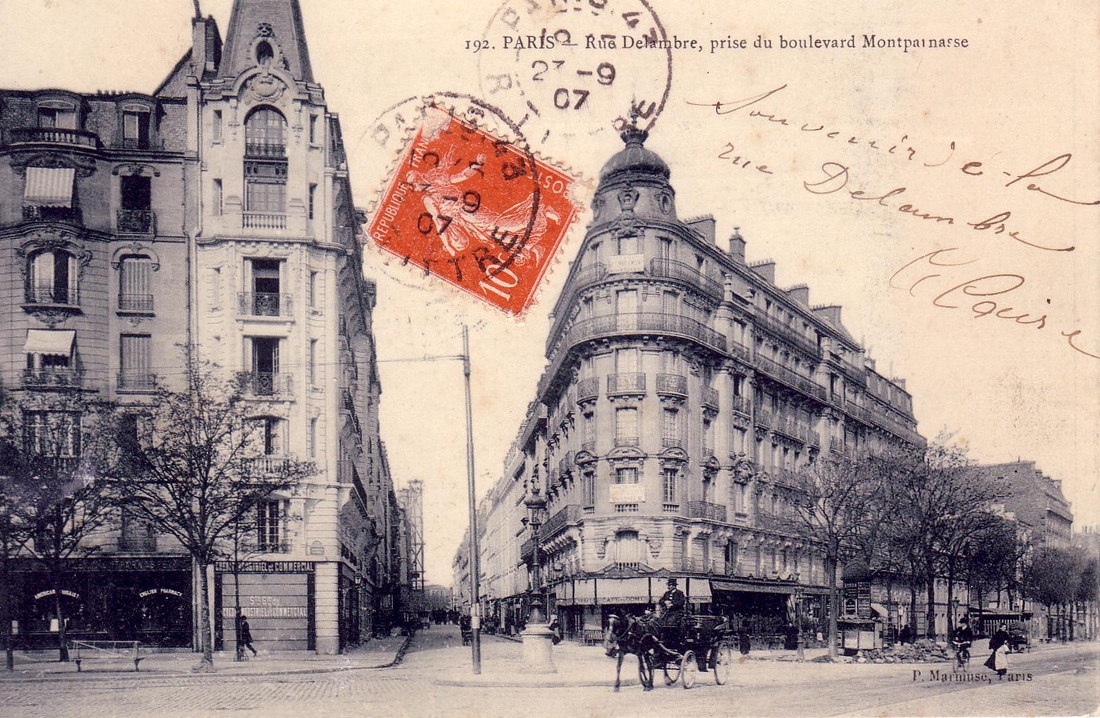

PARIS: RUE DELAMBRE

It seems therefore to have been about 1907, shortly after Cora’s own arrival, that Jan Gordon arrived in Paris. He headed to Montparnasse and found a room in a cheap hotel at 39 Rue Delambre in the 6ème arrondissement, on the southern fringes of the Latin Quarter. Jan briefly describes his arrival thus:

‘When I first went to Paris as a student I wrote to the great Zuloaga asking if he would take me as a pupil, he replied;

“Painting is a thing you have got or not. If you work hard it will come by itself.”

But I went to Julien’s academy instead.

Having spent a week on a nude drawing. The great day arrived when Jean Paul Laurens was to criticize. He looked me over from head to foot for three minutes, glanced at my drawing for five seconds and said, “ the arm’s too short.”

I walked out of Julien’s and never went back.

Nevertheless I had paid my school fees for the month.

Perhaps some Scotch ancestor restrained me from joining another school while as yet owning a place at Julien’s. I was at rather a loose end.

Luckily I had been persuaded to buy a thumb sketching box for oils.

It was a beautiful little apparatus made by Reeves. It carried two very thin wooden panels and a palette with paints all set out and was no bigger or thicker than a sketch book. The panels measured about five inches by six.

The charm of the Luxembourg gardens had from the first attracted me, and one autumn day, taking my sketch box with me, I tried a small sketch direct from nature in the Gardens.

A year later I was still working out of doors with my small oil box. I had joined no other academy, nor had felt the need for one. There was heaps and heaps to learn about art before worrying about the blessed nude again.

And I had saved all the art school fees.’1

Among the large artistic community he had made at least two friends, an American couple identified in his convoluted code as the ‘Praps’ (would that he had made life easier for his biographer). The Praps were both successful and ambitious and held regular soirées.

As was to be expected in that loose knit Anglo-Saxon community in Montparnasse Cora was a friend of the Praps, and was invited to one of these soirées where she noticed ‘a tall man with a shock of drooping dark hair who looked rather humorously distressed’ lurking out of the way in the kitchen. She remembered that she had seen him at Leconte’s2 restaurant ‘where he would sit unobtrusively in a corner, nose deep in a book while he ate – invariably the same meal, which the waitress would bring him without asking, and a bottle of beer … a fillet of herring, a steak and potatoes and a ‘mendicant’ – [a dessert of nuts, raisins and figs]’ which he had got into the habit of ordering because ‘... it saved him worrying over the menu for half an hour and still not being sure he had ordered the best…’

Cora was intrigued enough to ask another acquaintance about the tall stranger. ‘Oh, him. English Bohemian act. You can see him striding about the quarter, six miles an hour with no hat and a pea green overcoat. Some of the girls call him ‘Puree de Pois’. Not so bad as some, I believe.’ Curiosity aroused, Cora made further enquiries of another: ‘ “‘Puree de Pois’?. He’s a queer fish, got the Praps’ old flat in the Rue Villegature Segonde, [actually Rue Compagne Premiere] just opposite you. Public school man, I think, though you mightn’t believe it. Bit disgruntled over a girl just now4. She let him down, they say. He might interest you – etcher, had something in the last Salon5 Spends all his time sketching in the streets. I’ll see if I can introduce him.”’

Cora didn’t get her introduction on that occasion, but at least the mention of public school put him in the appropriate class bracket (some things never change). Cupid however had not failed to notice and was to show his hand a week or two later when Cora, unwittingly entertaining the ether addicted “ Ffeell” to tea, was surprised to answer the door to the tall stranger who had been sent to her studios by the acquaintance of whom she had made enquiries earlier – a belated introduction in fact.

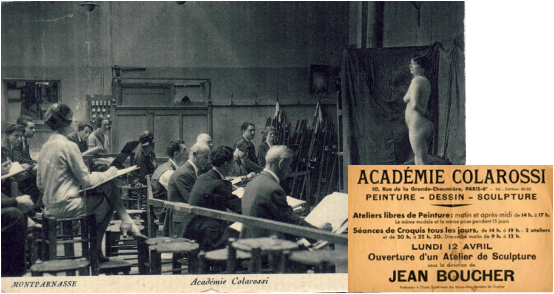

Relieved to be unburdened of the sole company of the ether fiend Cora delightedly enjoyed the humorous conversation of the quirky stranger, Jan Gordon, no less. When Cora told him of the broken etching press lurking in a corner that had been left by one of Cora’s friends from the Colarossi sketch class Jan eagerly made arrangements to return in the morning to examine and repair the press, no doubt stressing his engineering credentials! True to his word Jan returned, Cora having forgone her morning class to be in attendance.

Jan and Cora’s acquaintance soon blossomed into sharing a dinner table in the evenings. She was assured by his amiable companionship, reasoning that his disappointment over a girl precluded any of the unwelcome advances she had had from others. Though Jan’s appearance was not prepossessing, with his unruly hair, irregular shaving and dirty collars, “his speech and manner bespoke correct English education so clearly that I felt in company with something pleasantly easy to appreciate” (that middle class bonding again). Both had revolted into Bohemia – but only so far.

‘One day she met him in the street (Rue Campagne Première) where he lived at No 11, just opposite to no 6.’ (The building described in ‘The Girl in the Art Class’ is that of no 9 Campagne Première, a studio complex that still exists. 9 inverted is 6. The opposite side of the street is even numbered so perhaps 11 = 10 or 2?) As he was returning from a session painting in the streets, slung over his shoulder was a bag of painting equipment. Questioning Jan about his work, Cora was invited in to view.

Jan displayed a curious shyness which manifested itself as a dislike of asking certain questions, and he would spend hours trying to find an answer for something he would have learned in a few minutes by a direct question. And he was not a tidy man. Thus a corner of his room was piled with floor sweepings, paper and odds and ends, for he had not worked out the refuse disposal system of Paris. His lunch was bought in paper bags, and as he chose things entirely edible he avoided perishable refuse. Clothes and boots lay scattered all around. Cora sat in his only chair while Jan showed her his work … some 40-odd oil paintings on very thin wooden panels about five by six inches.

Cora was amazed that such minute work could be done by such a huge person. She thought he looked like a huge rabbit in a tiny hutch. A ground floor hutch which cost Jan 425 francs a year and from which he complained he couldn’t keep the cats out at night.6 What is clear is that Jan and Cora’s romance blossomed rapidly. This was no teenage romance, bearing in mind that Jan was now 25 and Cora 28. In those days she would have been regarded as being almost irrevocably left on the shelf of spinsterhood.

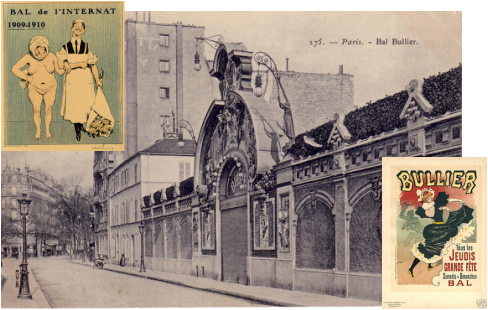

They were both fond of dancing and had become regular attenders at the Bal Bullier, a noted students’ dance hall opposite the famous writers haunt the Closerie des Lilas. Another favorite venue for dancing was the American-founded Cercle Internationale, started in an attempt to introduce American teaching methods into Parisian Art Schools. A superior sort of Art School and centre for student reunions, as opposed to the usual time worn and ramshackle Parisian schools such as Colarossi’s (there were already around 4000 Americans in Paris pre WW1). But the Cercle Internationale was far more formal than the easygoing Bal Bullier; Jan was expected to wear evening dress which he did not like (nevertheless, even a ‘bohemian’, educated as he was at English public school, found it necessary to carry formal evening attire around the world in those days!)

Cora gradually became aware that around the quarter and amongst the ex-pat community, she and Jan were beginning to be regarded as an item, for instead of other students pressing her for a dance she was left alone with Jan, and he, if Cora was occasionally invited to dance by another, did not seek out other dance partners.

Cora realised she was in love with Jan, though was unsure that her feelings were reciprocated. –

‘… I persuaded Arnold to buy a ticket7. It seemed that my intimacy had been marked by more than the concierge and Mrs Praps, I was very annoyed to note that other men students not only were less forward to claim dances, but they put them selves down on my programme for but a single dance, where formerly they used to claim two as a right and had often urged me for more as a favour. However since Arnold hid himself in the bar whenever he was not dancing with me, he had a clear programme to offer whenever I was free. This must have made me more conspicuous than before, but I did not care. Dancing with other men than him seemed almost insipid. If Arnold did not love me, dancing with him was as near as I could come to him; we were at least temporarily united in a blessed bond of mutual rhythm.

‘After one glorious dance, while we were in a dark corner of the gallery, Arnold bent forward, grunted and said explosively:

“Hey, I say Miss Carpenter. I want to marry you most awfully. Hey will you?”

After the dance was over, the caretaker, locking up for the night, must have been surprised to find two coats still hanging in the cloak room.

“Tiens” he said turning them in his fingers. One was black silk, a woman’s; one was of rough green tweed the colour of peas. He was puzzled. He was almost sure that all the guests had long ago departed. But to make sure he gave a shout: “On ferme!” which had the result of bringing us, both very abashed, from the gallery. The caretaker almost snorted with indignation as he helped us into our coats, and unlocked the door once more. But the tip which William gruffly passed to him left him scratching his head and shrugging his shoulders. ”Eh bien” he said ”on n’est jeune qu’une fois”

It was a glorious night, the most glorious God had ever made. Impossible to think of separating at once or going back to our solitary studios. So we walked along with steps which would have made you think that the ankle straps of Mercury had of a sudden sprouted from our slippers.

We found ourselves somehow on the boulevard St Michel.

“We must celebrate” said William, and led me with a new and sweet proprietorship into the cremerie. Here we ordered chocolate, a drink only too suitable for newly engaged lovers….’

That’s the version as related in ‘The Girl in the Art Class” and I believe it to be quite factual,albeit subject to some elasticity of time and of literary convenience.

At 25 and 28 years of age Jan and Cora did not want the conventional long engagement of those days. They convinced themselves of the wisdom of an immediate marriage and optimistically believed that their families would be equally enthusiastic, although friends mooted the idea that it would be better to marry first and then announce the fact. The path of true love is frequently bumpy and only happy lovers believe otherwise.

True to form, Frederick Turner played the part of dictatorial Victorian control freak. He, who had also married young and against parental opinion, predictably took extreme umbrage and “expressed suspicion” about the “indecent haste” of the arrangements. He wrote to Jan “my daughter’s friends, sir, are her own family”. Fine friends, the violent and possessive father who had “bullied her to the verge of a nervous breakdown” and the jealous stepmother who had confessed she hated her. The strong willed Cora was no doubt only too willing to make the break from that family in favour of the amiable and humorous Jan, who at 6 feet and some 13 stone provided more than a degree of physical protection as well as affection.

Jan’s family, by now at Wadhurst in Kent, where the Reverend Alexander Gordon was living in semi-retirement, put up a feeble protest and gave in.

Jan had never quite fitted in to the established pattern of this conservative and ecclesiastical family and was regarded as something of a cuckoo in their nest. Nevertheless, it seems they were kind enough to send an invitation for them to be married from their home at the end of that summer.

Jan and Cora had other plans and it seems Frederick Turner had not yet thrown in the towel.

A comedy of middle class errors*

1909—Frederick Turner turns up unannounced in Paris and plays the Victorian father figure.

the following text taken verbatim from 'The Girl in the Art Class ' by Jan Gordon 1927.

Setting: Cora's studio. 9 rue Campagne Première, Paris 6ème

Cast

William Arnold….. Jan Gordon

Raymonde Carpenter ….Cora Turner

Mr Carpenter……. Fredric Turner

Praps……. unknown American photographer

La concierge.... herself

Reynolds…. unknown upper class Englishman

It was a warm afternoon a few days later, William and I were both working, he printing etchings, I was making a drawing from a nude who I had got in for a séance. Once more she was the girl who had had a child by "accident" William was stripped to his shirt and trousers,

his sleeves rolled up, his collar undone.

"Tiens " said the girl to me. " il a la peau blanche vot'mari, plus blanche que moi. " There was a sudden thump on the door, and without waiting for my answer the door was suddenly burst open and there framed in the darkness of the corridor striking an attitude of dramatic parenthood was father.

But at the sight of William and the naked girl his jaw dropped.

"Good God girl!" he exploded.

"Mon dieu monsieur." cried the model.

She caught up her clothes, for a model may be quite as shy of being seen by the uninitiated as any Susannah. In her haste she mixed her garments, tangled her combinations hopelessly and finally swore at Father, "fiche le camp vieux satyr' she snapped, would you have me exhibit myself to the whole corridor”? The tone rather than her words brought understanding to father, and he modestly shut the door with himself outside.

“Good lord," I whispered, "it’s father."

"Serve him right "said William," he looks crusty though," "Oh do be tactful." I urged.

"Why, naturally." said William.

At last the model was dressed and William opened the door. "Come in Mr Carpenter, please" he said with the voice of an elephant trying to imitate a dove.

"Its…s quite safe now you know."

My father gave him a stare and a gulp.

“Safe?” said he “Safe sir? Humph.”

He transferred his glower from William to the model. She felt so vividly the terror of his appearance that she scurried from the studio without waiting for her money. I ran after her with a five franc piece.

When I returned I heard father say gruffly

"I did not come to Paris, sir, to talk of the weather."

"Well I could have guessed that you know,” said William in a voice that implied, "Now my good old pal, don't let's have any nonsense between us."

On my re-entry father turned his back to William and became a parental Jove once more.

"I have never before understood” he said with a histrionic catch in his voice “that my daughter was living a life of such depravity."

"Oh, come, I say," ejaculated William

"I was not addressing you sir said my father. “I am now forced by what I see to say what I feel at once. I said depravity. I mean depravity. I find her consorting with shameful women, such as that one who has recently withdrawn herself, properly cringing, and with a half naked man in the room, too." "Now look here Mr Carpenter," said William.

"You have no right "

"No right sir," said father, swelling, "Indeed, I am glad to learn that a father has no right sir!"

"To make a fool of yourself, I was going to say." went on William emphatically. "No, sir, I deny your right to make a fool of yourself."

Father was so surprised he could only gasp

William grabbed the chance to interrupt

" You don’t know any thing about artists or models, that girl is probably a decent girl. She earns her lining and respects herself. In her way she is virtuous."

Father was struggling with his collar.

"Virtuous?" he cried; "in her way? What do you mean sir? There is no 'in her way', virtue is virtue sir. Don't quibble. I find my daughter consorting with a shameless woman, and you say she is virtuous, in her way and call me a fool. I never heard anything……… "

Another knock at the door, and before I could interpose, William roared out "Entrez."

I think he was glad of any interruption

The interruption was from the man known only as 'Praps', host of the party where Cora first noticed Jan, He gauchely made himself at home and asked for tea, Jan grabs the excuse to

go out for brioches to accompany the tea, the American Mr Praps fails to notice Frederick’s growing agitation.

"Say, Mr Carpenter," he went on, as soon as I had handed him his tea, "that’s a smart little gurl of yours. She's getting on fine in this art business. I reckon she couldn't have fallen better than with this Arnold. He looks rough, but I tell you sir, he's a cracker-jack; yes, believe me. A cracker jack..." Out of the corner of my eye I could see father sitting like an Egyptian statue. He had determined to master himself. No scandal, above all, no scandal. He must be calm

" because I've always said to my little woman. “Miss Carpenter's one of the brightest prettiest little gurls round Montparnasse. Believe me. Sir”

Father quivered all over with suppressed rage. His daughter called pretty to her face by a low-class bounder like this

But never in my life have I seen father exercise so much self control. Publicity is a wonderful policeman.

William (Jan) returns with another Englishman intending to introduce him as a 'gentleman' of

equal class to Fredric in order to placate him, but this newcomer does not get on with Praps who has by a muddled joke managed to further complicate things by implying that Raymonde (Cora) is pregnant.

Mr Reynold then tactfully withdrew and we three faced one another again. I noticed that father looked queer and much older.

"I had no idea no idea” he added , " that my daughter was living in a mad house and in a

house of sin. Twenty years ago I’d have given you a thorough hiding, madam; yes, I would.

But now I suppose I must be grateful to this—er gentleman for taking you off my hands.

Well, sir, I am grateful. You have ruined her, I am glad you have sufficient decency of feeling to repair your fault as much as is possible." "What the deuce are you talking about?" said William

"I understand from that photographer fellow,” said father, "that it is common talk that this girl who calls herself my daughter, to my sorrow, is about to have a baby..." Father !" I cried, "Father!"

What the devil do you mean?" growled William

Why that fellow stated it distinctly. His—er—little woman said so. I presume she is not his wife—another of this girl’s sordid companions."

"Good lord what an idea," said William " Yes, she is his wife only she makes bloomers, you see, hum, I mean puts her foot into it. That was only one of her jokes that went wrong."

“A joke in very poor taste then” cried father

"Everything is poor taste here," answered William, " everything. Even art. Ever seen Matisse? Good lord, you can't imagine how childish that fellow is. Why you won't you believe me when I tell you that…"

“Oh shut up, William," I said "whatever does father know of painting?" thank you, thank you," said father, "I know what I like, even if I don't know anything about painting. And I tell you miss, I don't like your friends, I don't like your life, and I don't like this man."

“Well, anyway, " said William, with so quizzical a look that I shuddered at what he might be going to say, "I don't think you'd better dislike me too much, sir. And I really believe you'd better let me marry her; because although she is, well, what you might call immaculate, she's hopelessly compromised."

Compromised!" cried father. "Do you mean to say, sir, that you have deliberately and caddishly compromised my daughter?"

"My dear man," answered William soothingly, "every girl who lives in this place is compromised. Hopelessly compromised. Why she's been compromised for two years at least." My God." cried father, clutching his hair, "Why do we have children?" William whistled a bar under his breath. I recognised it as a refrain to a vulgar song that he sometimes sang called. " Couldn't help it, had to."

Father stood up and began striding up and down the studio, ignoring us both, apparently in deep thought. I believe he was quite aware he was play-acting somewhat. After a while he said:

"I shall make no decision immediately. I shall sleep on it as I always do. Whether I shall feel flattered to hand my compromised daughter to you, sir, for the protection of your name, or whether I shall take her home, I have not decided. However, Sir, I will endeavour to be moderate. I will know you better if I can. You will dine with us at some artists' resort, and we will spend the evening together. I hope, sir, that this meets with your approval?" He sat down on the divan.

"That’s awfully good of you, father” I said gratefully. "Now then you'll both have to go out while I dress. William, you run off and shave. Father, you walk round on the boulevard and look at the shops for twenty minutes."

"But why should I go out?" said father, "Have you no bedroom?" "Bedroom" I said "why goodness no. That’s my bed you are sitting on." "This is your bed!" ejaculated father, jumping up.

“Well. I told you she was compromised." said William at the door. He walked away down the passage.

Father put his hand to his head once more. He seized a large sketch book that lay on the table, it fell open at a drawing of a nude girl. He slammed it shut, cleared his throat, seemed to be going to speak, changed his mind, and suddenly marched out of the studio. Soon William was back tapping at the door. He had shaved and put on a clean collar-- most necessary—and we sat contentedly waiting for the return of father. Time passed but no father had returned. Suddenly a thought flashed into my mind.

“Good Gracious, William!" I ejaculated.

“ Father’s lost,”

He's lost in the corridors. I forgot all about them. Heaven knows where he will have got to, You must run and look,"

"Confound the old chump," said William, and rose reluctantly to his feet and went out. He had hardly been gone five minutes before a thump at the door announced the return of father, ushered by the fat concierge.

"Je vous ramène vot’ père,, mademoiselle" she said " je lui ai dit comment vous êtes une fille vraiment sage."And she gave me a greasy wink that infuriated me.

Father was very distant, his pride was injured. I tried to apologize to him; he cut me short. "I suppose that you turned me out into that labyrinth amongst pigsties as a practical joke," he said."

"I really, really forgot," I protested. "Why, William has gone to look for you." "I could never have believed in such a hole in a civilised town. And to think that a daughter of mine could live here; could be content here, after the way she's been brought up. Scandalous."

I suddenly wondered if, by bad luck, father had penetrated to the lavatories on the walls of which some of the puerile inhabitants had scrawled dreadful obscenities in French.

The door opened again and William poked his head in.

"I'm awfully sorry I can't find the old bird," he said

"The old bird sir," snarled my father, jumping to his feet has found his own way back, no thanks to you!"

"Oh, sorry, no offence" replied William cheerily.” you know how we people talk. No meaning in it. Just a locution. Apologize, sir."

Father grunted.

Supper at Souvenir's where we took him because it looks so respectable, was a period of stress, but the food was good enough to mollify father and the wine put him into a complacent humour.

A family conclave was called at eleven o'clock in my studio to hear fathers' decision. William arrived for it at half-past eight, and I spent the intervening two hours and a half urging him to be tactful. He tried to prove to me the qualities of his tact by methods which, however grateful they were to myself, would, I fear, have had little effect upon father. William had made himself quite presentable,--presentable from father's point of view, I mean. I preferred him in the rough myself.

Father arrived and took the wicker chair, William and I sat on the divan-bed. I expect father thought this conjunction was ominous.

"Well. Sir," said my father pompously to William, "I have been considering the case. I do not approve of you sir, I tell you frankly, but on the other hand, seeing the milieu in which my daughter has chosen to settle, I presume that I must be grateful that she has not proposed to me some Hottentot or ether-maniac as a son-in-law, or that she has not followed the habits of her companions and dispensed with decency altogether. Do I understand that you are in a position to support my daughter?"

"Well I can support her for a couple of years,” said William, "and then she can support me for a couple of years, and by that time we ought to be able to bumble along somehow."

"I cannot view the prospect with complacency," said my father, "nor the future you hold out to her of—ha! —bumbling along, as you call it. I have always understood that a gentleman did not propose to marry a girl without prospects of supporting her properly in accordance with her station."

“But don't you see, sir,” said William, " we aren't gentlemen here, we're artists. That makes all the difference."

This is a serious discussion." said my father. "I'm being perfectly serious," returned William.” We’re artists, not soldiers."

Do you mean to tell me seriously artists aren't gentlemen?" said father bending his brows. "It's awfully difficult to be both at once," said William "You see, sir they both mean totally different things."

"Then sir," said father, "you have decided me out of your own mouth. I shall withdraw my daughter from this society of cads and lunatics, and I shall endeavour to rehabilitate her in her proper sphere where she was bred."

"Oh, I was bred there, too," said William, "but one can get over it, you know. I have; she has." "That is for me to say." said father stiffly.

Isn't it rather for me to say?" I interposed.

“You will do as you're told, Raymonde," said father.

"I am very sorry father," I answered," but, without wishing to appear rotten. I will do what seems best for the future. After all it is my future you are both discussing so abstractly." "Your father will always act in your best interests girl." said father sharply. "Well," I replied," you really can't expect me to see things from your point of view. I can't bring myself to think that you've always acted in my best interests. I made you send me to the Art school in London; I came to Paris against your wishes."

"And a pretty mess you've got yourself into, miss," said father grimly. "But please go on. I'll hear you."

"I do not consider myself to be in a mess," I declared, " I am not complaining, and it is my life that is being made. It seems that I must choose between you two. If you insist, father, I shall choose William I know at least he loves me; he loves what I am. He accepts all that is there, the faults as well."

"Do you insinuate I do not love you Raymonde?" cried father.

"I don't know” I answered, "I don't know what you love. I only know you do not love what I am. You may love something-a memory, an ideal of daughtership, a possession. You may have loved the possession of mother, the possession of a daughter, but I deny that you have ever loved either mother or myself for what we really are. And now you would drag me from the first person who has known me as I am. Well I won't go."

"If I had you at home I’d flog you miss," said my father angrily," that’s the medicine you need."

"I suppose you'd beat love into me," I retorted as angry as himself.

"Pshaw," cried father, "what's the good of wasting words. You're a wanton, miss; that’s the truth, I'm down right ashamed of you. I cut you off from the family. Marry in haste and repent at leisure then. May God sustain you in the future. Good-bye."

He picked up his hat and cane and stalked out. William took me in his arms to comfort me.

"I'll be your father, too," he said.

Oh no you won't." I retorted. "I've had enough of fathers. I want a husband."

"Then I'll have to be someone else's father." said William.

I smacked his face for that.

There was a sudden bang on the door, William jumped to open it. Father stood outside.

Father !" I cried gladly, ready at once to make it up. He ignored me.

Sir," he said gruffly, " will you be so good as to conduct me out of this damned building?"

It was the first time I had ever heard father swear.

In 1918 Cora spoke to Jan of her desire to write a novel. Jan suggested she make it autobiographical starting from the point when her father tried to "throttle her."

Why Jan ended up putting his name to it is not known, I can only surmise it made it easier to publish. It has been my eternal frustration that Jan disguised so many of the characters in this book which has prevented it from being a highly valuable narrative of life in Paris of that era, It is only by endless cross reference to other writings of Jan Gordon, such as the two sole remaining volumes of his diaries, that I have been able to establish a degree of verisimilitude to Jan and Cora's life during this period.

Frederick Turner apparently carried out his threat to disown Cora. His funeral a few years later was a distressing affair for Cora who had to deal with her stepmother Jessie’s jealousy. ~~( Jessie McKenzie Partington, Cora had 3 half sisters, all childless, mostly living in Cornwall for most of their married lives)

And so, having deciding against marriage in Paris after hearing of a plan to make a fete of it in Montparnasse, they came back to England to be wed, to Chelsea where a friend of Cora’s had sent an invitation. On July 7 1909 at St Luke’s Church they had in the words of Jan, that doubly romantic event ‘a parental interdiction and an artistic wedding’.

Cora’s friend lived at 111 Elm Park Mansions while Jan lodged at 8 Stanley Studios. The witnesses at the wedding were Jan’s mother Blanche and Cora’s elder sister Ida, by then married to one Stanuwell, a solicitor in Belfast.

Among the many coincidences that have been party to these years of research, one stands out. In June 1985 I bought my first painting by Cora Gordon from a man in those same Stanley Studios overlooking Elm Park Mansions, almost 76 years to the day.

For their honeymoon they spent time in Wadhurst, Sussex, with Jan’s parents, where Cora whiled away the summer drawing pigs, and then they went later to her home town of Buxton where, according to ‘Gradus ad Montparnassum’8 they rented a small shop for an exhibition hoping to swell the coffers. Cora’s father by now having moved with his new family to Blairgowrie in Scotland, the coast in Buxton was clear and here Cora still had friends and acquaintances among the townsfolk who remembered her with affection.

They were to return to Paris with the “problem of winning fame and a competence within the next four years”, for that was how long their combined assets would keep them afloat. “…To start an etching school and to keep as deadly secret the fact that Jan had only been studying art for 18 months.”

Cora returned to Paris with what is written in ‘GAC” as being one of the prettiest compliments she had ever received from the wife of the farm labourer next to where they stayed in Wadhurst – “…I’m sorry you are going – you aren’t like a lady somehow”.

notes;

6 A ground floor studio supports the theory that Jan was living in rue Campagne Premiere.

7 This passage is verbatim from ‘A Girl in the Art Class’, and I believe it to be as near to a personal reminiscence as it is possible to get this far removed in time

8 The tickets were for the dance at the Cercle International, a dance which Jan disliked as he had to wear evening dress, such was ‘Bohemia’ those days that even the arty set felt obliged to pack evening dress!

9 Blackwoods magazine

10 The girl in the Art class

1 Anecdotal from A Stepladder to Painting, 1st edition

2 In reality this was the cremerie LeDuc, a favourite eating place for the Anglo Saxon expats.

A restaurant is still on the same spot, though now very different from the humble eatery Jan and Cora knew

3 In Gordon-speak this is the rue Campagne Premiere; Cora had a studio at No 9

4 This was a girl known only by her surname, Gellibrand she was a sister of the later to be notorious Paula Gellibrand

5 to date the earliest definite mention I can find of Jan showing a work in Paris is 1912.

|

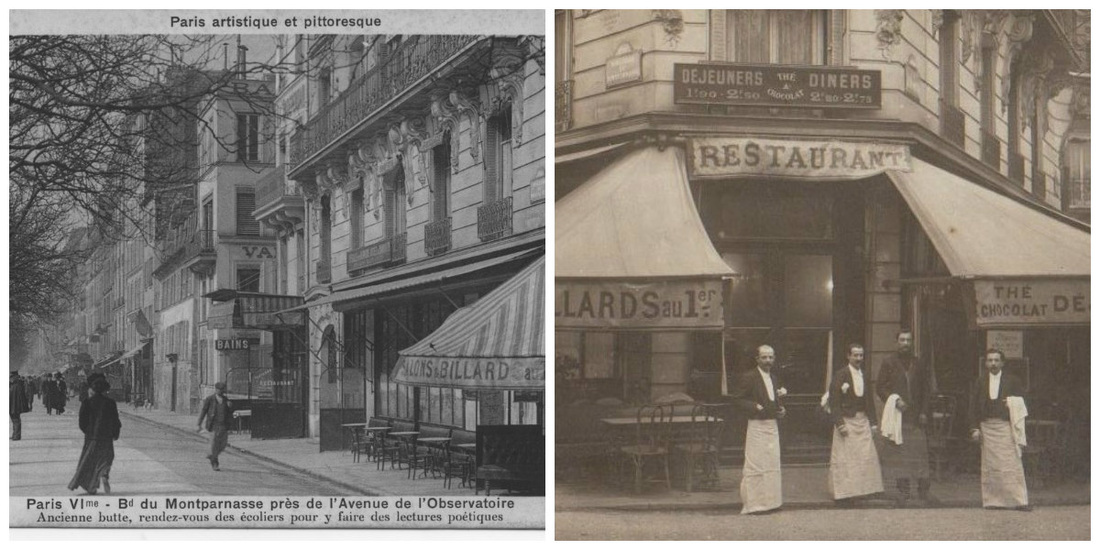

Montparnasse 1906

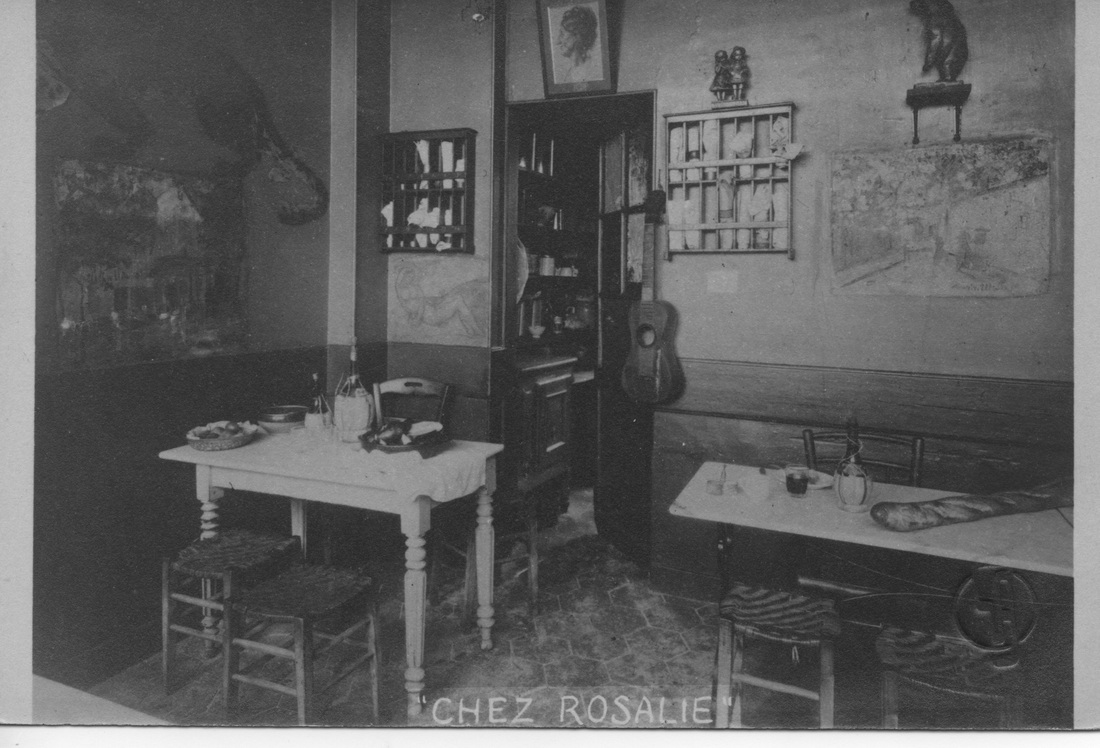

The Paris of 1906 that Jan Gordon and Cora Turner knew was far from the notorious post 1920 crazy years that have been most reported upon. It was the tail end of the Belle Epoque when gentlemen still wore top hats and tail coats seemingly everywhere and wore elaborate beards and whiskers in order to convey the correct degree of gravitas. The Montparnasse ‘quarter’ lies on the Southern heights of Paris just inside the site of the recently demolished city walls, and lies across part of the 6th and 14th arrondissements of Paris, just outside the Latin quarter proper which was centred around the lower part of the Boulevard St Michel. It runs roughly from the Place de Rennes and the Gare Montparnasse eastwards to the Bal Bullier and the Closerie de Lilas at the top end of Bvd St Michel, and includes the streets to each side. It's axis is the Vavin crossroads formed where the Boulevard Raspail cuts across Bvd Montparnasse, Bvd Raspail was finally opened south of Vavin in 1906 and at each corner were to be found the cafes and other institutions that made Carrefour Vavin “the centre of the world” The famous artists resort the Café Du Dôme was opened in 1898 on the site of some ramshackle sheds and grog shops; La Rotonde opposite was but a workman’s bar with an impressive entrance courtesy of the truncation of the building it occupied to make way for Raspail. The restaurant Baty and the Hôtel de La Haute Loire, favoured first stop off point for English artists were directly opposite the Dôme and on the north side, on the corner of the Rue de la Grande Chaumiere where the Academies of Colarossi and others were, was the famous store Hazard wherein just about every nationality that had flocked to Montparnasse could be sure of finding its favourite food specialities. By the side of the Dome is the rue Delambre, which contained a number of hotels of varying comfort. Jan is recorded as living at No 39, At the end is the Boulevard Edgar Quinet and its still extant and vibrant market, leading to the Rue Gaite and the dance halls and Theatres. The southward extension of Boulevard Raspail housed at 212, the Crèmerie Leduc, favoured restaurant of British and Americans and respectable enough for an unaccompanied young woman such as Cora Turner. A little way further up Raspail and opposite is the southern end of rue Campagne Premiere, if one turned down this little side street to return to the Bvd Montparnasse, at the far end on the left is still to be found at No 9 the block of studios occupied by Cora Turner and opposite were, until the late 1920s a row of ramshackle two story houses one of which may well have been Jan Gordon’s lodging, after his first digs in Rue Delambre.. At no 3 Campagne Premiere was the restaurant Rosalie were Cora was known to have frequented, eaten, perhaps even along side Nina Hamnett and Modigliani, who was both fed during his impecunity and berated for his drunkenness by his famously fiery Italian compatriot, Rosalie who had once been a favourite model of artists past. From here it is but a short walk back to the rue Grande Chaumiere and its academies and art supplies shops, across the rue Notre Dame des Champs, to the Luxembourg gardens favoured sketching haunt of Jan Gordon. Montparnasse proper terminates at the southern end of the Boulevard St Michel and the Closerie Des Lilas, favoured haunt of the ‘intellectuals’ and the Bal Bullier, which a dance hall favourite of Jan and Cora, where all the latest South American dance crazes such as the Tango scandalised the bourgeoisie. This then was the Paris that Jan Gordon and Cora Turner found themselves in around 1908/9, each hoping and wondering if they could make the grade and earn a living as working artists. |

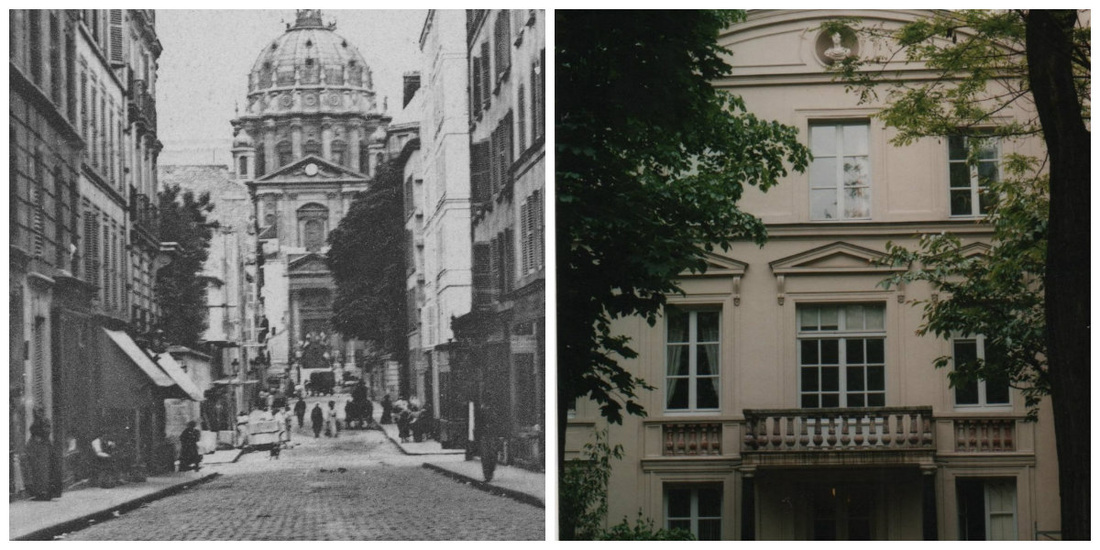

The newly weds returned to Paris to resume their art studies. To live exactly where is uncertain; the unreliable catalogues for the various salons in which they showed their work always show their address after marriage as 39 rue Delambre, but certainly they took rooms in 6 rue Val de Grace, in the converted roof space which Jan has described.

The whole building was home to a number of artists ,among them Alphonse Mucha.

In the photos above, of the Rue Val de Grace above, No 6 was behind the trees on the far left, and their studio was in the rooms under the arched roof .

Cora continued to attend classes at Colarossi; in a 1950 Studio magazine article about their old friend Bernard Meninsky she recalls her 1910 memories of Colarossi, of being surrounded by famous artists among fifty or so draughtsmen around the model.(Cora was a regular attender of the illustration classes).

The students at the Paris academies were are real mix of every nationality, with a large contingent of Scandinavian men and women. It is logical to speculate that one of these introduced them to the Pension Fürmann in Belgradstrasse Munich.

The whole building was home to a number of artists ,among them Alphonse Mucha.

In the photos above, of the Rue Val de Grace above, No 6 was behind the trees on the far left, and their studio was in the rooms under the arched roof .

Cora continued to attend classes at Colarossi; in a 1950 Studio magazine article about their old friend Bernard Meninsky she recalls her 1910 memories of Colarossi, of being surrounded by famous artists among fifty or so draughtsmen around the model.(Cora was a regular attender of the illustration classes).

The students at the Paris academies were are real mix of every nationality, with a large contingent of Scandinavian men and women. It is logical to speculate that one of these introduced them to the Pension Fürmann in Belgradstrasse Munich.

Started by a Swiss German, Heinrich Fürmann and his wife Louise this pension was run as a bohemian refuge for impecunious artists.

It was very cheap, if indeed the owner could be bothered to collect his rents, and the students would subscribe to Saturday musical evenings. Jan and Cora seemed to have been popular students there

Jan and Cora stayed there for around a year circa 1911/12, and are recorded as returning there in 1930. There exists in a German private archive an extensive written and painted record of their times there, and Cora has written about the place in an article posthumously published in 1950 as a chapter in the book 'Travellers Quest'. [more on this shortly]

It was very cheap, if indeed the owner could be bothered to collect his rents, and the students would subscribe to Saturday musical evenings. Jan and Cora seemed to have been popular students there

Jan and Cora stayed there for around a year circa 1911/12, and are recorded as returning there in 1930. There exists in a German private archive an extensive written and painted record of their times there, and Cora has written about the place in an article posthumously published in 1950 as a chapter in the book 'Travellers Quest'. [more on this shortly]

That they worked solidly and steadily at their art is shown by the fact that they had began to have work accepted for show in a number of galleries, notably around 1910 in a show at the Walker gallery Liverpool.

1910 Walker gallery autumn exhibition and the London salon

1911 London Salon summer exhibition, and new English Art Club

1912 London Salon.

But what seems to have been a turning point in their fortunes came in 1912 when Jan and Cora took the plunge with their meagre resources and hired a gallery in the Rue Faubourg Montmartre, at the Gallery Henri Manuel at number 27, which in this contemporary photo had its entrance just behind the lamp post and the little group of people.

1910 Walker gallery autumn exhibition and the London salon

1911 London Salon summer exhibition, and new English Art Club

1912 London Salon.

But what seems to have been a turning point in their fortunes came in 1912 when Jan and Cora took the plunge with their meagre resources and hired a gallery in the Rue Faubourg Montmartre, at the Gallery Henri Manuel at number 27, which in this contemporary photo had its entrance just behind the lamp post and the little group of people.

This is the exhibition described below in the following excerpt from Jan's Article Gradus ad Montparnassum and can be dated with pin point accuracy by the phrase

“voyager dans les Indies comme un hero de Kipling” which must have amused Jan as it is a direct quote from a newspaper review of April 1913 written by the indefatigable chronicler and historian of all things to do with Montparnasse, Andre Salmon, under the nom de plume of La Palette.

His florid but enthusiastic review is given here.

Mme Cora J Gordon possède entre autres dons les plus

charmant et le plus périlleux de tous, le don de l'esprit

elle contraint de songer le plus ingrat des péchés celui qui ne

sera point pardonné... pourtant.

.... pourtant qu'ils nous suffise, pour être d'accord avec les

exigences de notre raison, de proclamer que Madame

Gordon a son tabouret à la cour de la reine fantaisie, La

Fantaisie! Nous lui rendus en ce jeune siècle beaucoup

d'honneur.

Elle apparaît triomphante, vivifiant notre littérature qu'elle

sauve du morne ennui; mais elle heurte trop ravement

encore a la huis des académies peinture pour l'honorer

comme il convient, restituons à cette aimable salvatrice son

nom authentique, et saluons l'imagination retrouvée.

C'est a ses suggestions. D'une extra ordinaire richesse.

Qu' obéit madame Cora J Gordon.

Elle compose avec une aisance féminine, toujours

souriante, des féeries aimables et tumultueuses. C'est d'un

art fantastique, c'est à dire oppose au romanesque procédant

étant soumis aux vertus classiques.

Bref, Madame Cora Gordon a, des le début de carrière.

Reconnu le sens fabuleux qui,peut être accorde le plus rare

et est les plus riches créateur.

Madame Cora Gordon fournit des thèmes aux poètes; elle

assemble, en assurant la pérennité de leur valeur, plastique,

le matériaux du conte.

Ces OEuvres sont les plus souvent, moins des réminiscences

des mille et une nuits ou d'un Songe d'un Nuit d'Été que les

illustrations avant la lettre, des beaux poèmes jamais écrits.

On bien elle ose rajeunir les thèmes éternels.

Un talent si délice ne vas pas sans malice dans l'invention.

La frivolité de ses soeurs est, pour l'artiste un sujet jamais

tari: elle hausse,toutefois l'exercice de cette frivolité assez

pour conserver le sentiment de la noblesse dans l'art.

Ses compositions sont autant de ballets mais des ballets à

l'antique, qu'il faut considérer comme repose au cours de la

tragédie.

Voici des princesses nue fustigeant des crapauds

monstrueux; elles sont nues mais extravagamment coiffées

car la “nature” « cet objet les plus douteux de nos

méditations » n'éblouit pas exagérément Madame Cora

Gordon. Voici une bayadère dansant par les pourceaux,

l'actrice entre le prince et le financier; la courtisane en

prison; voici le nain fardant, coiffant la Belle; la laideur

faisant le toilette de la beauté!

Ceci dit, gardons-nous de nous méprendre et de de ne prêter

à celle qui nous séduit par un art aussi mobile, aussi varie

que des qualités d'ordre purement que des qualités d'ordre

purement littéraire.

Madame Cora Gordon a fait encore peu de peinture; mais

elle s'affirme l'un des plus habiles gravures de notre temps;

elle n'ignore rien d'un art dont la noblesse et d'être, plus que

toute autre, aussi un métier. Or nul n'est grand artiste, s'il

n'est patient, scrupuleux et savant ouvrier.

La formation du talent de Mons Jan Gordon est singulière.

Ce peinture ne vint point à la art par les routes ouvertes.

Nourri des sciences exactes, comme un héros de Wells;

vagabond des Indes, tel un personnage de Kipling, il

s'essaye, d'abord, entre deux descentes à la mine, non pas

la à transfiguration du paysage légendaire du pays des

enchanteurs mais al al glorification du travail. On verra ici

quelques eaux-fortes de cette époque; elle apparaissent d'un

art dépouille, d'un métier simplifié qui fait songer aux

ouvrages des première réalistes. Plus tard Mons Jan Gordon

sera sensible

a la grandeur frénétique de capitales et il et assez piquant

d'observer qu'en tout temps semble à lui même, il obéit à

une unique direction, qu'il burine eu son mirador de colon,

devant la jungle, ou dans son atelier de Londres ou de Paris.

Peu à peu il eu vient à considérer les paysages citadins

qu'ainsi que des sommes superposées d'éléments humains,

et c'est pour l'artiste une grande révélation.

Un instant, il s'essaye a des compositions allégoriques pour,

très vite, n'être plus retenu que par un désir d'exacte

psychologie.

Ses oeuvres les plus récentes concrétisent toutes ses

pensées, résument tout ses efforts.

Après une cure de solitude, face à la nature nue, dans le

Tyrol Bavarois, voyez ces quelques “Portraits de

Montagne” qui nous consolent de la manière Suisse des

monstres que les savants nommeront un jour, Alpinistes à

pinceaux!

Mons. Jan Gordon célèbre aujourd'hui la foule et la nature,

l'une et l'autre prisonnières de la cité et rien ne caractérise

mieux son tempérament que certain (nº 13). Mardi Gras au

Luxembourg »

Il me semble que ce n'est point par une inclination attendrie

de son esprit que Mons. Jan Gordon s'attache volontiers,à

peindre des foules enfantines.

N'est ce que pas plutôt qu'il tente par la---- logique

simplification, réminiscence de son passe scientifique- de

créer une image de la multitude au moyen d'éléments

complets en quoi se retrouve l'innocence primitive.

Les efforts de Mons Jan Gordon et de Madame Cora

Gordon sont-ils contradictoires? Non point. L'un n'a autre

guide que sa volonté, l'autre se soumet à l'aimable loi du

caprice: tous deux répugnant à la moderne barbarie du

sentiment, sont sous tenus par une même et bienfaisante

culture.

La Palette

**pseudonym of Andre Salmon

It is apparent that Andre Salmon was an early admirer of Jan and Cora's art, certainly they had gained some journalistic fans as they began to be noticed in Parisian newspaper columns and their work had several mentions during 1913.

So it is very likely that Andre Salmon was the person who introduced them to Paul Fort's Tuesday evening soirées at the old Closerie des Lilas opposite the Bal Bullier dance hall.

“.....where before the war we used to make merry with all the lights and lesser lights of the modern art movement..

“voyager dans les Indies comme un hero de Kipling” which must have amused Jan as it is a direct quote from a newspaper review of April 1913 written by the indefatigable chronicler and historian of all things to do with Montparnasse, Andre Salmon, under the nom de plume of La Palette.

His florid but enthusiastic review is given here.

Mme Cora J Gordon possède entre autres dons les plus

charmant et le plus périlleux de tous, le don de l'esprit

elle contraint de songer le plus ingrat des péchés celui qui ne

sera point pardonné... pourtant.

.... pourtant qu'ils nous suffise, pour être d'accord avec les

exigences de notre raison, de proclamer que Madame

Gordon a son tabouret à la cour de la reine fantaisie, La

Fantaisie! Nous lui rendus en ce jeune siècle beaucoup

d'honneur.

Elle apparaît triomphante, vivifiant notre littérature qu'elle

sauve du morne ennui; mais elle heurte trop ravement

encore a la huis des académies peinture pour l'honorer

comme il convient, restituons à cette aimable salvatrice son

nom authentique, et saluons l'imagination retrouvée.

C'est a ses suggestions. D'une extra ordinaire richesse.

Qu' obéit madame Cora J Gordon.

Elle compose avec une aisance féminine, toujours

souriante, des féeries aimables et tumultueuses. C'est d'un

art fantastique, c'est à dire oppose au romanesque procédant

étant soumis aux vertus classiques.

Bref, Madame Cora Gordon a, des le début de carrière.

Reconnu le sens fabuleux qui,peut être accorde le plus rare

et est les plus riches créateur.

Madame Cora Gordon fournit des thèmes aux poètes; elle

assemble, en assurant la pérennité de leur valeur, plastique,

le matériaux du conte.

Ces OEuvres sont les plus souvent, moins des réminiscences

des mille et une nuits ou d'un Songe d'un Nuit d'Été que les

illustrations avant la lettre, des beaux poèmes jamais écrits.

On bien elle ose rajeunir les thèmes éternels.

Un talent si délice ne vas pas sans malice dans l'invention.

La frivolité de ses soeurs est, pour l'artiste un sujet jamais

tari: elle hausse,toutefois l'exercice de cette frivolité assez

pour conserver le sentiment de la noblesse dans l'art.

Ses compositions sont autant de ballets mais des ballets à

l'antique, qu'il faut considérer comme repose au cours de la

tragédie.

Voici des princesses nue fustigeant des crapauds

monstrueux; elles sont nues mais extravagamment coiffées

car la “nature” « cet objet les plus douteux de nos

méditations » n'éblouit pas exagérément Madame Cora

Gordon. Voici une bayadère dansant par les pourceaux,

l'actrice entre le prince et le financier; la courtisane en

prison; voici le nain fardant, coiffant la Belle; la laideur

faisant le toilette de la beauté!

Ceci dit, gardons-nous de nous méprendre et de de ne prêter

à celle qui nous séduit par un art aussi mobile, aussi varie

que des qualités d'ordre purement que des qualités d'ordre

purement littéraire.

Madame Cora Gordon a fait encore peu de peinture; mais

elle s'affirme l'un des plus habiles gravures de notre temps;

elle n'ignore rien d'un art dont la noblesse et d'être, plus que

toute autre, aussi un métier. Or nul n'est grand artiste, s'il

n'est patient, scrupuleux et savant ouvrier.

La formation du talent de Mons Jan Gordon est singulière.

Ce peinture ne vint point à la art par les routes ouvertes.

Nourri des sciences exactes, comme un héros de Wells;

vagabond des Indes, tel un personnage de Kipling, il

s'essaye, d'abord, entre deux descentes à la mine, non pas

la à transfiguration du paysage légendaire du pays des

enchanteurs mais al al glorification du travail. On verra ici

quelques eaux-fortes de cette époque; elle apparaissent d'un

art dépouille, d'un métier simplifié qui fait songer aux

ouvrages des première réalistes. Plus tard Mons Jan Gordon

sera sensible

a la grandeur frénétique de capitales et il et assez piquant

d'observer qu'en tout temps semble à lui même, il obéit à

une unique direction, qu'il burine eu son mirador de colon,

devant la jungle, ou dans son atelier de Londres ou de Paris.

Peu à peu il eu vient à considérer les paysages citadins

qu'ainsi que des sommes superposées d'éléments humains,

et c'est pour l'artiste une grande révélation.

Un instant, il s'essaye a des compositions allégoriques pour,

très vite, n'être plus retenu que par un désir d'exacte

psychologie.

Ses oeuvres les plus récentes concrétisent toutes ses

pensées, résument tout ses efforts.

Après une cure de solitude, face à la nature nue, dans le

Tyrol Bavarois, voyez ces quelques “Portraits de

Montagne” qui nous consolent de la manière Suisse des

monstres que les savants nommeront un jour, Alpinistes à

pinceaux!

Mons. Jan Gordon célèbre aujourd'hui la foule et la nature,

l'une et l'autre prisonnières de la cité et rien ne caractérise

mieux son tempérament que certain (nº 13). Mardi Gras au

Luxembourg »

Il me semble que ce n'est point par une inclination attendrie

de son esprit que Mons. Jan Gordon s'attache volontiers,à

peindre des foules enfantines.

N'est ce que pas plutôt qu'il tente par la---- logique

simplification, réminiscence de son passe scientifique- de

créer une image de la multitude au moyen d'éléments

complets en quoi se retrouve l'innocence primitive.

Les efforts de Mons Jan Gordon et de Madame Cora

Gordon sont-ils contradictoires? Non point. L'un n'a autre

guide que sa volonté, l'autre se soumet à l'aimable loi du

caprice: tous deux répugnant à la moderne barbarie du

sentiment, sont sous tenus par une même et bienfaisante

culture.

La Palette

**pseudonym of Andre Salmon

It is apparent that Andre Salmon was an early admirer of Jan and Cora's art, certainly they had gained some journalistic fans as they began to be noticed in Parisian newspaper columns and their work had several mentions during 1913.

So it is very likely that Andre Salmon was the person who introduced them to Paul Fort's Tuesday evening soirées at the old Closerie des Lilas opposite the Bal Bullier dance hall.

“.....where before the war we used to make merry with all the lights and lesser lights of the modern art movement..

The Closerie des Lilas in its pre 1914 days as Jan and Cora knew it. On the right a 1908 photo of the Closerie waiting staff ; it is intriguing to think that Jan and Cora may have been served drinks by these chaps.

After the 1914-18 war the Closerie became a very more upmarket affair and a favourite cafe of the likes of Hemingway. It's still in business these days if you can afford it.

Possibly more than a little bit of literary license to gain some kudos here on the part of Jan Gordon as the key to their entry to the soirée seems to have been Cora's talent for imitating the roar of a camel which in the argot of the day had an obscene meaning that Cora was unaware of. They can have spent little time among these lesser lights as 1913 was the year in which they spent summer in Majorca. (This was described in an anecdote in London Roundabout.)

Jan wrote a short article, At the Cafe des Rosés for the New Witness, [ read here in the drop down menu], while in London on war work. It is unreliable as to the identification of the characters mentioned among the lesser lights of the Closerie des Lilas as Jan used only initials, not always the an initial of the true name as some characters are telescoped into a composite for better effect.

The only certain identifications are of Paul Fort, the “prince of poets..” and their friend Andre Salmon; one or two other are possible subjects for conjecture but likely only written in for effect. Otherwise I am sure Jan would have given a bigger clue as I have found from other sources such as his diary,was his usual wont.