|

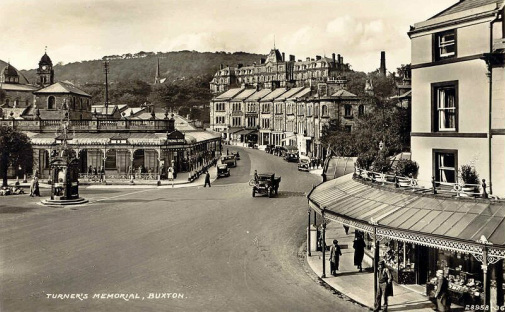

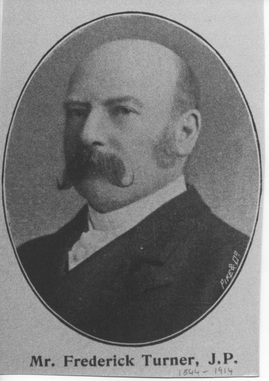

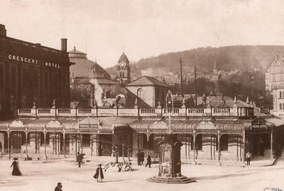

For this chapter I have had to draw heavily on Jan Gordons 1927 book, "A Girl in the Art Class" This book is an account of Cora's early life,up to and including their meeting in Paris, their engagement and marriage. That this book was in some sort a thinly disguised auto-biography I have been able to establish by crossing referencing a number of primary sources, mostly later writings of Jan Gordon. It has made me despair for the valuable biographical record that has been lost; why Jan Gordon chose to name the principal characters Raymonde (Cora), and William (Jan) I have no idea. The era when it is set, around pre 1914 Paris art schools is thinly documented and this book if it had been truly established as factual with real names instead of the bizarre invented ones Jan used would have been a real work of reference. As it is, the first best clue is the enigmatic flyleaf dedication , "To my wife JO from whom I have stolen all that I have not stolen from others concerning Raymonde." the second is a passage in Jan Gordons Feb 1916 diary when he discusses writing such a book of biography. "....Jo said she had the feeling that she wanted to write a novel.....we discussed the subject. I suggested she should be autobiographical from the time her father tried to throttle her till our marriage bringing in College Hall and Paris, the queer feeling in feminine student circles and lots of real atmosphere........" "....we further discussed the novel. she decides to start it at the house of her friend where she took refuge after the attack and I suggested ending it while she is dressing for the dance when I proposed...." To me this suggests that her fathers attack on her was more violent and serious than is suggested in the book. From this point text in Italics is taken verbatim from the book 'A Girl in the Art Class' Buxton Derbyshire in 1879, the year of Cora Turner's birth, was a town on the up. Based around the thermal baths fed from the hot springs of the Peak District it was also proud of the new Devonshire Hospital, which overlooked the town. This splendid edifice was built under the patronage of the Duke of Devonshire and his treasurer for 43 years was one Samuel Turner. Samuel Turner, who was also a church warden of St Johns Church, was obviously wealthy enough off to send his son Frederick to Oxford to study medicine whence he qualified as a general practitioner, though for his entry on Cora's birth certificate, he is described as a surgeon. By 1879 Frederick Turner was living in a Grafton House, The Quadrant. in the middle of Buxton, opposite the thermal baths and the space where, in 1878 would be erected a drinking fountain as a memorial to his father Samuel. (This was rather ignominiously knocked down by a Ford van in 1959, and recently re -erected a short distance away from its original position.) Into this eminently respectable household, with its cook, housemaid, nurse and page boy, was born to Frederick and Sarah Turner, one cold March day in 1879, Cora Josephine, sibling to Reginald, 8 and Ida. Frederick was apparently the archetypal Victorian father; detached, humourless, stern and a bit of a bully with a famously bad temper. Short, stocky and powerfully built, he was something of an athlete in his younger days with an interest in gymnastics, football, boxing, fell walking and hunting. Conversely it seems that he was regarded as a brilliant doctor, who zealously looked after the sanitation and water supply of Buxton and the welfare of its inhabitants, by whom he was highly regarded. He was a Freemason, magistrate, school governor and wholesale Conservative supporter. 1"His rulings as a JP were often marked by leniency, especially toward men, and he was charitable.” According to one of his obituaries “he was loved on account of his genial and gentlemanly bearing, and the intense and loving interest he manifested in all the ways of those who dwelt around him.”2 No doubt this view of him could well be interpreted as meddlesome and interfering, depending on one's point of view, for he was not viewed in this same light within the confines of his own home. His irascible nature and foul temper did not endear him to his family or his servants, who came and went on a regular basis. Cora would remember "Freud could have probably explained him. He could find no outlet for the humours that stewed in him than by venting them upon us, him. He could find no outlet for the humours that stewed in him than by venting them upon us, the unlucky women of the household... During my childhood I was often beaten black and blue with a hunting crop but he could always burst into tears over me, declare that he was a tender and loving father and strut off with an easy conscience ... My poor mother was better off out of the way when he was rampaging..”3. But as Cora says, a child knows no different and she was consoled by a number of dogs one her own, with horses and cats, and she became adept at keeping out of her father’s way. In many respects Cora must have had quite a robust outdoor upbringing. Her father was a keen fell walker and out door sportsman. Doubtless she would have learned to horse ride as she certainly had no problem with long periods of horse riding while in the Balkans later. Certainly from a young age she was a very strong walker, one had little option in the brisk open spaces around Buxton. She was well able to match the noted fell walking pace of Arthur Ransome who seems to have been a friend of the family in a way I have not yet been able to discover, although there is possibly a family connection to be uncovered. In Ransomes auto biography he relates an episode where Cora came to Coniston for a few days and on a general walk over to Ambleside... "....put us all to shame by her tree climbing skills when we stopped for bread and cheese and beer by the Drunken Duck..." at Barngates, Ambleside. The Ransome connection with Cora has been difficult to to establish; that Cora knew Ransome before her marriage to Jan in 1909 is evident; as Frederick Turner was such an archetypal Victorian parent Ransome must surely have been known to the Turner family for Cora to be allowed to spend time with him. At one time I speculated that Ransome may have been the athletic rower subject of Cora’s crush as touched on in The Girl in The Art Class Jan’s disguised biography of Cora but the age gap and unconfirmable datelines do not support this conjecture. Certainly though the friendship continued and it is fact that circa 1907 Ransome took a studio in the same studio block , 9 Rue Campagne Première, in which Cora lived around that time. Arthur Ransome and the Gordons certainly had several mutual friends. As Cora grew up she became an ardent reader, a trait nurtured and encouraged by her mother who harboured hopes that she would become an authoress. She read steadily and grittily through her father's extensive library. Her father, on the other hand, veered more toward musical aspirations. In "Girl in the Art Class" she says it is a wonder her liking for music survived given that her early life was so pestered by piano and violin lessons that "ate up her playtimes` However, her primary childhood love was books and, encouraged by her mother, she sent in three essays to a children's competition in a well known ladies' periodical from which she received the encouragement of four honourable mentions. At the same time, Cora was also nurturing a love of drawing, which was not encouraged. "Art is niggardly in benefits” In 1949 Cora recalled "I was trained to be a Musician, but only to play to bored people in the evenings, I was intended as an ornament in the home… In fact, after returning from school in Brussels, where she learnt the piano and viola, she went on to study at Manchester School of Music, becoming an accomplished pianist. Nevertheless, as she realised, she was being educated to be little more than an ornament to a husband: … " those talents were to be a halo behind something that was to wear pretty clothes, grow a good bust, have a nice smile and a kind heart, converse pleasantly, dance well, win a husband to be proud of, hold a position in society and breed the number of babies appropriate to my husband’s income.” The strongly independent minded Cora however had other ideas; she was her father's daughter and quite ready to assert herself should the need arise. The need was not far away. Her mother Sarah died, 16 March 1896, just one week after Cora's 17th birthday. Cora was brought back from Brussels to become mistress of the Turner household. “I became an orphan plaything. Something to be taken out and advised. He was generous to me and reaped applause from me. He chose to be facetious over my household experiments. But the servants still came end went "It fair breaks my nerves to have the muffin dish pitched at me head whenever master isn't satisfied.”4 For a while Cora managed well enough to find and hold her position in the middle class, complacent, small town society of Victorian Buxton. She began to come into contact with people outside her own social standing, and was slightly amazed at the fact that the lesser classes" could have skills and talents of their own, such as the waterworks clerk who, in order to learn to play the violin made his own, It was a revelation to her that a person of such lowly station should possess such talent. Frederick held no such doubts: "each to his place" that was the order of things. However, fortune had lain other plans for Cora,now around 20yrs old, and while her father was prospecting around for another wife, Cora contracted some eye disease which kept her bedridden for some weeks and fearful of going blind.To amuse herself she entered a small competition in a weekly ladies magazine,[Home notes,motto, The hand that rocks the cradle rules the world], The competition was to make amusing figures from ink blots, to Cora's surprise she won the £2gns first prize, which, albeit trivial, encouraged her to to pursue her natural talent for drawing It was not long before Frederick began to tire of the state of widowhood and in a surprise announcement to Cora he informed her of his intention to marry Jessie Partington, a cousin of her mother's, and somewhat younger than himself. Cora was not troubled by this she knew Jessie of course, so there was no shock of the new, and she foresaw the prospect of being liberated from the chores of day to day household management. She would now get more time for the fun in life, and above all for the drawing which she was practising more and more. It was not to be, however. "On the very evening of his return from honeymoon father scowled at me and asked what the devil I was doing. Such a thing had not happened for three years.”5 There was only the briefest honeymoon period with Jessie. Cora was unprepared for the backstage position she soon found herself occupying. At first, Jessie eclipsed her in her father's sight and she found her stepmother acted as a buffer between her and her father. Then Jessie became pregnant with the first of three daughters she was to have in rapid succession. Jessie became jealous and showed a quite spiteful attitude to Cora in contrast to her earlier generosity. One of Cora's pastimes was fencing, at which she had become quite adept. One afternoon she was practicing in her old nursery with a local vicar's son. “Suddenly the door was flung open and father literally purple with rage stood in the doorway “how often have I told you?” he shouted "I won't have such a terrible din going on. Turn that fellow out. How dare you have him here without my permission, its disgraceful. It's positively improper. It's.... ," I flung my fencing foil into a basketwork chair “One can't do a thing in this rotten house”, I flared out at him. But father hit the young man a back-hander and jumped at me with an odd grunt. He knocked me down. I scrambled to my feet. 'You beast, " I spat at him, I was as angry as himself, and as pig headed, Then I don't know clearly what happened. Everything whirled. He caught me by the throat. 'You beast," I gasped again. Things were like a cubist picture made cinematograph. The scared servants and the amazed youth pulled him off me while I was only half strangled. I became quiet with an odd feeling that everything had finished. I mean that nothing would ever happen again, the feeling that a nun would have when a nun takes her vows. And then in some five minutes or so life had gradually crawled to its normal rapidity, Blunderingly I swore the young man to secrecy and the servants also Then with very shaky knees and a sore throat I crept to my own room…”6 She then took refuge in a friend’s house in Buxton (This is the incident which Jan, in his diary of 1917 suggested Cora take as a starting point for her autobiography) Cora had had enough. She gave an ultimatum to her stepmother. Either her father apologised or she would leave the house. Jessie, more concerned than anything that there would be no scandal, offered £10.00 for expenses and Cora took refuge with friends in London. On the train journey down she pondered her options: For a woman of that era and social group the choices were but two... marriage or a profession. Marriage did not tempt her, nor was there a prospective husband in view. A titled actor with local connections had once before, after an amateur theatrical performance by Cora complimented her and made the offer of training with an amateur repertory company. It was inevitable that Frederick would take extreme unction at this offer. "I'd see her in her coffin first' was his response. As Cora later commented, he had a habit of consigning her to her coffin on a regular basis whenever she displeased him; as for example when she wanted a bicycle, or to take up golf, or when a woman with an ineligible son offered to take her touring in Europe and so on and so on Cora decided that she would pursue Art as a means of earning a living. She had a legacy from her late mother—money that her mother had gone to pains to keep out of the hands of her father. So Cora dug her heels in, and by threatening her Father with the ignominy of his daughter taking to the stage she achieved his grudging concession that Cora could enrol at the Slade school of Art, in London and reside in Colleges Hall a safe lodging for unchaperoned young ladies. And so, in 1902 Cora became a student of Fine Art Anatomy at the famous Slade School of Art. Cora studied here from 1902-1906, gaining certificates in anatomy, perspective painting and drawing. Always having enjoyed her school days away from the tyranny of her father, she felt at ease and began to mix with a more cosmopolitan crowd than she had hitherto known within the confines of Buxton, The women of College hall were for the most part medical students who considered themselves a little bit better than artists. But it didn’t seem to bother Cora after he first awkwardness of adaption. She seems to have had a good time and made companions. They amused themselves with fencing and music in winter, tennis in the spring, with tea or coffee parties, theatricals and charades, all with out the hindrance of the opposite sex. During these cloistered years Cora had little contact with men. There was an incident with an over amorous bus conductor in Sloane Street, which left her facing a long walk back to Gower Street late at night but otherwise the nearest she seemed to come was when she and her class found themselves working above the raucous male students in their noisy composition class in the studio a floor below. At these times the prim students of College Hall “kept themselves courteously distant.” Cora could not, however, resist a hankering sympathy with a small group of girls who were a little more at ease with their male co students. “They by no means kept the men at arms length… they weren't earnest, they loafed they flirted, they came late and went early, they laughed at and some times joked with the professors they even smoked in working hours, the hussies!!" 7 Yet Cora admitted her surprise at the quality of their work, despite all this laxity. After the conclusion of her studies in 1906, Cora had another hurdle to cross. She had never succeeded in making her father apologise. He had forked out for an allowance and the school fees that Cora had accepted in lieu. But on returning to Buxton she realised that her father was intending to use her as housekeeper and nanny to his new brood of children. Jessie had by this time produced two more in rapid succession, as befitted a good Victorian wife. So Cora, not intending to become her father's unpaid drudge, played her ace card. She announced her intention to finish her art training and education in Paris. Naturally he forbade such a thing, didn't he know all about Paris and what went on there? Cora stood her ground and defied her father. He tried to reason with her, to cajole her but Cora had her Mother’s legacy and her father's obstinacy and determination. At last, after one evening discussion when he lost his temper and told her to "go to hell the way you want to " with an insinuation that Cora had the intention or destiny to become a “loose woman". Cora’s way forward was clear. A fortnight later, in late 1906 or early 1907, Cora Josephine Turner, aged 27 finally broke loose and packed her bags for Paris, heading for a pension that a girlfriend had recommended near the Latin Quarter, possibly in the Boulevard Raspail, not yet fully constructed, or more likely in the Rue Notre Dame des Champs home to a number of board and lodging houses for respectable young women art students who were coming to Paris in increasing numbers from England and the USA . An informative period article written especially for young ladies wishing to study in Paris can be found here [high light and click link] |

In the Rue Grande Chaumiere off the carrefour Vavin and in easy reach of her lodgings in the rue Notre Dame des Champs, Cora enroled herself inthe Academie Colorossi, then a very progressive art school in that it was the only one to allow female students to draw from the male nude in life classes; it was also cheap, and flexible with classes.

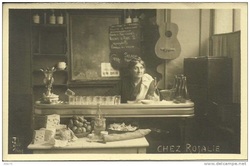

An amazing find.

This is the little modest eating place in the Boulevard Raspail which in 'Girl in the Art class' was renamed 'Le Contes' the shift from that to Le Duc is obvious.

What really excites me is that the woman with the smile turning her head to the camera could well be Cora. I am undecided.

certainly two of the other people in this pic could be interpreted as characters in that book, the little dark haired hatless woman is holding a dog which might easily be the dog mentioned several times that Cora looked after.

All conjecture sadly.

Also identifiable in the book, to be found at No3

a few doors down from No 9 was the famous 'Chez Rosalie cafe', It's fame was at its peak before 1914 when Rosalie fed and humoured Modigliani, Utrillo and their ilk , who covered her walls in paintings as payment.

Rosalie Tobias was an Italian ex artist model who would not serve anyone who looked too prosperous; Sadly almost all Modiglianis paintings went to feed the stove.

Its certain thatCora would have eaten here.

|

Cora stood her ground and defied her father. He tried to reason with her, to cajole her but Cora had her Mother’s legacy and her father's obstinacy and determination. At last, after one evening discussion when he lost his temper and told her to "go to hell the way you want to " with an insinuation that Cora had the intention or destiny to become a “loose woman". Cora’s way forward was clear. A fortnight later, in late 1906 or early 1907, Cora Josephine Turner, aged 27 finally broke loose and packed her bags for Paris, heading for a pension that a girlfriend had recommended near the Latin Quarter, possibly in the Boulevard Raspail, not yet fully constructed, or more likely in the Rue Notre Dame des Champs home to a number of board and lodging houses for respectable young women art students who were coming to Paris in increasing numbers from England and the USA .

The Rue Notre Dames des Champs was, before 1914 a street where a number of lodgings for specifically respectable unaccompanied young women could be found; most respectable seemed to be the Villa Des Dames, pension de famille, but there is no suggestion I can find that Cora lodged there. It is certain that for a short while she lived on this street. It was handy for the Rue Grande Chaumiere and the Académie Colarossi where Cora had enrolled as being the cheapest. That it was also the first Académie of Art to allow woman students may well have played a big part in Coras choice.

Cora did not stay in her first lodgings for long; she moved along the Rue Notre Dame des Champs to two cheap 5th floor rooms, and then later to Rue Campagne Premiere to a studio in the rabbit warren of artists studios,still extant, at Number 9.

Cora settled down to a round of classes at Colarossi, and exploring Paris, eating at various cafe and restaurants including certainly the noted artists cafe 'Rosalies', just next door to No 9. Dealing with the occasional casual Roué encountered by, on one occasion, thumping him the chest with her fist in a fencing lunge, and another persistent pest she led into, and then abandoned, lost, in the unlit warren of corridors of the No 9 studios.

Aware of the sparsity of her funds she turned to giving English lessons,and to Illustrating articles for the monthly magazine "The Idler' , for which apparently she never got paid.

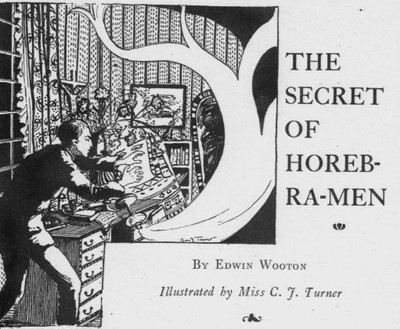

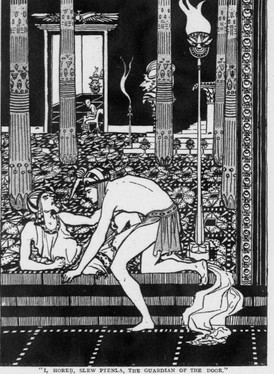

These articles are difficult to track down, but I show one, published in May 1909 to illustrate a short story by Edwin Wooton.

Aware of the sparsity of her funds she turned to giving English lessons,and to Illustrating articles for the monthly magazine "The Idler' , for which apparently she never got paid.

These articles are difficult to track down, but I show one, published in May 1909 to illustrate a short story by Edwin Wooton.

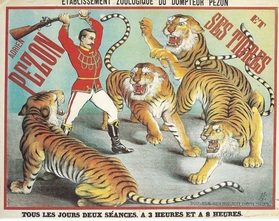

In later years Cora would work these little anecdotes of Parisian life into her lectures, one intriguing one concerns her sketching at Pazons Cicus and menagerie. Out of hours the owner would allow artists in to draw for free.

As Cora tells it....

‘Why don’t you go and draw in Pezon’s menagerie ?’ said an artist to me. 'out of show hours they'll let you in for nothing. You'll get cheap models

‘chimpanzees lions learning tricks, and that Hyena of theirs is a first class specimen of a downright mean beast.'

With pockets full of pencils, pens, pads, and a few biscuits for lunch I set off for the menagerie. Curiously enough, at first my tiger drawings

looked wrong. I was so used to drawing men’s faces that my tigers looked human. Many well-trained artists find that they can’t help making cats

and bulldogs and frogs uncannily like themselves, too human altogether.

In time one begins to see the character and proportion of an animal with a much keener eye.

Luckily for me the President of the Society of Animal Painters was sketching there every day, a tubby little man with a French father-of-the-

family beard and that very French custom of finishing everything off tidily with a proverb.

He was kind, and criticized the over-human proportions of my tiger drawings and helped me to observe better. By the time my tigers became

quite tigery the weather changed and one morning a downpour began to find its way through the leaky tent. I unfurled my umbrella and tilted

it for shelter.

‘Snarl. Woof. BANG., The cage containing a huge tiger rocked and shuddered as the beast furiously flung itself against the bars.

‘Mademoiselle’, yelled the attendants who had been sleeping on chairs tied in rows. ‘Mademoiselle Quick! Shut that umbrella!The cage is too

weak for such a rage. The tiger, he cannot support umbrellas!’

I snapped that umbrella to like a shot.

‘Discretion,’ said the President of the Society of Animal Painters, ‘is

the better part of valour.’

Several years later a bowler-hatted little man knocked at our studio door.

I had now become ‘Madame’.

‘My plea is this,’ said he; ‘it is that I plan to take an exhibition of pictures round France in a caravan, to sell them for the artists. I am only interested in pictures of fairs, circuses, and zoos. In the Salon I saw your husband’s picture, a merry-go-round--I am interested.'

So was I, very much interested. For all his prosaic appearance this dull-looking little fellow seemed to be an original, as the French put it- un

numéro.

‘You might doubt my integrity,” he said, unrolling a large colour picture of a tiger, an extra fierce creature, bounding in mid-air, very yellow

and black, whiskers, claws, glaring eyes, all most carefully drawn, and a dreadful tongue as red as red flannel.

‘This,’ he said, ‘was entrusted to me by the President of the Society of

Animal Painters, and he told me an interesting story about it .... A young girl was drawing in Pezon’s tent, the day was wet, she put up her--’

‘Umbrella!’ I continued. ‘The tiger roared and bounded---and----’

I finished the story with ‘La jeune fille c’était moi ’.

It would be wonderful to find the painting mentioned in this story, who knows where it is now?