Jan and Cora were invited in the early 1920's to give talks on their travels on the fledgling BBC, firstly playing Spanish music, then a week later giving a talk on their travels in the Balkans. These first radio talks were regarded by them as a something of a disaster after they took some coaching from a ham actor.

Later on, in the USA they had become used to public speaking and took part in A Swedish hour on a New York radio station which was also according to one of their anecdotes something of a shambles.

Much later during the 1930s they had become far more accomplished and confident, due to teh amount of public speaking they were doing on their lecture tours.

Jan's book, 'Piping George' was even adapted and produced on radio as a one act play, although how that odd book came across would be a wondrous thing to hear again. Sadly too early in the history of Radio Broadcasting for the recording to have been saved.

(The play ,produced by Eirene Fearon was aired on Friday 30 November from the Coventry Opera House.)

The story related below is taken verbatim from 'London Roundabout'. It would seem to tell of the ill fated Marconi TV system.

Jan and Cora were always keen to try a new experience. In the USA they had bit parts in films as guitar players and Jan even played a part in a film shot in Paris after they returned from the USA. try as I might I have not been able to find the film,or even a definite title for it in the British film library or the French one

After extensive research in Uk and France, far as can be established the film was either "l'Enigmatique Mr Parkes" or Un homme en habit".

All traces of either film have been lost.

So, here below "Wireless" from the London Roundabout

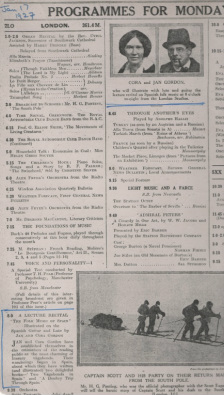

Now, back in Old England, we had been wondering whether in the move from Savoy Hill to its modern palace at Langham Place the B.B.C. might not have mislaid the memoir of our previous fiasco. Apparently they had, for one morning a pleasant voice hailed Jo on the telephone.

" That Mrs Gordon? "

" Yes."

"B.B.C. speaking. We are wondering whether you could give us a talk for school-children on Czechoslovakia? "

A short pause ensued, while Jo was fighting with her conscience.

" I'm awfully sorry," she answered, trying to make her voice as delightfully transmissible as possible, a sort of sample voice, " but we have never been there."...........

.................................................o0o...............................................................................

We looked at the letter with mixed feelings:

I shall be pleased to see you for a television test on Tuesday.

I should be very glad if you will bring with you any costumes you would like me to see. . . .

Yours faithfully,

t he British broadcasting company

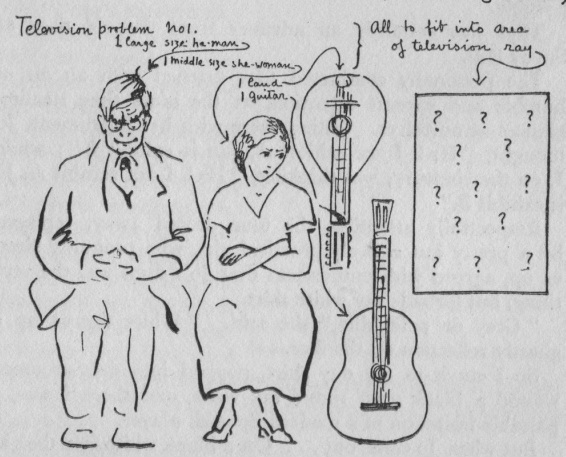

For we had rashly suggested that the television department might be interested in a selection of our Spanish folk-tunes played on the laud (or Spanish lute) and guitar, the former instrument being practically unknown in England, and Jo perhaps the only performer on it in the island.

Now that our suggestion had been taken seriously we began to wonder whether we could pull it off. Playing and talking before people are easy enough; one borrows from their interest and sympathy. The audience helps you on. But playing before these relentless mechanisms is a different matter. These automatons automatize you, and to fit their Robotism you must yourself become something of a Robot. Could we do it?

" Bring with you any costumes …"

What sort of costumes? No hint in this official letter. No circular with rough general suggestions. Jo looked out her most likely costumes, and selected a peasantish dress spotted with large red roses and a white Polish shawl, also redly beflowered. We then remembered that Steven Spurrier had been making television drawings for the Radio Times.

" Hello! That Steven? Look here, old chap, what's the best sort of garb for television? "

" Black and white," came back the voice of experience. " Stripes or squares—something striking."

We tossed Jo's wardrobe round in despair. There was black, there was white, but of black and white judiciously blended or contrasted nothing.

" Have to make one! " cried Jo, and took the first bus to Burnet's.

An hour later she returned with a packet of black-and-white-striped cotton.

" Hope that's startling enough."

She flung herself at a table with pencil and paper.

" Something like that," she said, showing a hasty scribble of a robe de style.

But I had to cut out the skirt, and an experienced and altruistic friend fashioned the frock for us, and had Jo fitted into a maze of diagonals like a camouflaged ship at the end of the Great War.

Then how we practised! Thrum, thrum, thrumpitty, thrum! We had to get the music practically automatic. It had to be so automatic that one could almost play the music and do the family accounts at the same time.

One feels horridly self-conscious going into the grand entrance of the B.B.C. carrying instrument-cases. It is like a Punch pen-drawing by Arthur Watts: hugely tall, massive pillars shooting upward, and in the far corner a tiny desk with two polite clerks. And from settees against the wall other artists (?) watch enviously to note whether you have an appointment or have merely blown in from the unemployed spaces. The feeling is exactly that of entering the lobby of a big movie lot in Hollywood.

From this gigantic hall we passed suddenly into corridors so narrow that they come as amazing contrasts to the palatial exterior. The courteous young man (B.B.C. manners are as impeccable as the accents of the announcers) led us to bronze doors that hid the large lifts.

" Going down," says the liftman sepulchrally. And down you go, two storeys below the pavements, into the silent guts of the earth, where no external sounds can penetrate. So that the narrow gallery into which we were now ushered was really a kind of mine-gallery, the gallery of a mine of sound.

The gallery opened into a lounge lit by subdued lights, with the strange rigid sense of modern refinement, one modernistic picture, one modernistic table, one modernistic ash-tray, and a pot of quite unmodernistic flowers. Here we were deposited to attend our fate.

Waves of nervous depression came on, until we gradually became aware that from the far distance a thin, disembodied voice was declaiming musically:

" Tom, Tom, the piper's son,

Stole a pig and away did run. . . ."

Then a flute and a saxophone played a rapid obbligato, in which Tom's criminal and hasty steps were intermingled with the pig's squealings.

Tom, Tom went on stealing the pig with a number of musical variations, while a group of solemnly serious people, all walking with the rigidly, columnar stiffness of the personally conducted tour, sidled into the lounge.

" Here," said the young and spick conductor, " is where the artists wait. On the right are the artists' dressing-rooms;on the left and at the end are the studios. We find that many artists, even the better ones, seemed almost incapable of doing their best out of their usual surroundings, so in the studios we have had to introduce as many of the normal theatre fittings as we can. We even provide audiences, so that the presence of the microphone is felt as little as possible."

That was certainly an advance from the old days at Savoy Hill.

The personally conducted tour listened with an air of humble and earnest attention, at the same time stealing glances at ourselves. Sitting there with her instrument, Jo thought, "Ha! I am exhibit A, Jan is exhibit B"; while I, on the contrary, was thinking, " Ha! I am exhibit A, Jo is exhibit B."

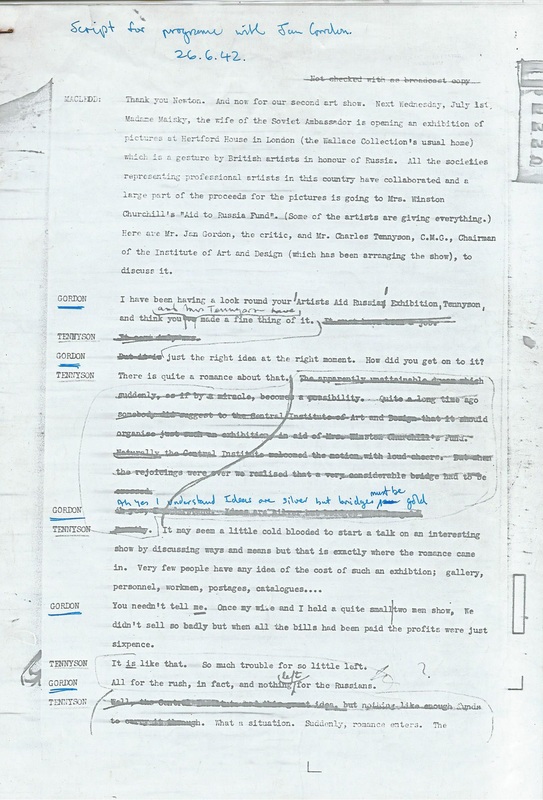

Respectfully attentive, the tour drifted away, replaced by a pretty but actively practical girl, who promptly sized us up, agreed with enthusiasm that Jo's dress was the very thing, but forbade my white shirt.

" Grey or pale blue," she said. " White throws up a ghastly reflection on the face.

So I stuck to my day shirt, popped into dress-trousers, wound a black scarf round my waist, and there I was, a passable imitation of a modern Spanish player.

But when Jo came out. . . On a blank white face the girl had drawn black outlines round the eyes, thick black eyebrows, black lips, and grey shadows. I had often seen Jo as a black-and-white drawing without any sense of strangeness, but now to see her as a black-and-white reality was almost repulsive. Odd that what looks quite natural on paper seems horrible in nature.l

Then the audition began.

Nervous? There was no time to be nervous. In a big, dark studio we faced an oblong opening in a blank wall. In the oblong window stood a black box, from which played a flickering white square brilliance. This flung on to a screen a patch of vibrating illumination about two feet six wide and four feet high.

The problem before the girl was how to fit into a quivering oblong two feet six by four feet one large-sized man, one middle-sized woman,and two instruments, leaving them space to play and not get entangled in each other's movements.

"Can't be done," I said to myself. " This audition's a frost from the start."

At the television department of the B.B.G. they must be experts in the art of adroit condensation. Bit by bit the girl and an assistant compressed us till, by a miracle, we managed to fit inside that flickering oblong. Whenever we had tried a new position we had also tried a few bars of music, so that by the time the final fit was achieved all our nervousness had flown.

Yet, even so, to play was not easy. Conditions were very peculiar. When I looked down at myself I seemed to be drawn as if with thin strips of dark and light, like the lines of a pen-and-ink drawing. Actually these strips were not stationary, but composed of tiny spots of light travelling so fast that they seemed to be continuous lines. Whenever these speeding lines of light cut a narrow diagonal line a different effect was produced. Then the vibrational nature of the light was revealed clearly, and the strings of my guitar and of Jo's laud seemed not to be straight lines at all, but rapid zigzags. When, in addition, I found that my fingers seemed also zigzagged the problem of playing without errors became serious. To paraphrase the nursery rhyme, I might have improvised:

There was a crooked man,

Played on a crooked string,

And with a crooked finger made

A television ping. . . .

In fact, the girl said to Jo, " Some people are so disconcerted by the effect of the ray that we have to stand in front of the light till they get used to it."

First we played a jota, or hota, as the Spaniards pronounce it. Then I played a farouka in solo, scraping the strings with the backs of my nails, beating out the time on the sounding-board, and generally showing off all the various tricks that characterize the Spanish guitar. While I was playing my solo the girl showed Jo into the operating-room, where, before a desk set with dials, a young expert twirled knobs. In a corner an oblong square of light about as big as a postcard flickered. Suddenly he placed the knobs in a proper adjustment, and clearly on the small screen I appeared, thumping and banging.

" Those hand-movements are interesting," said the girl, " but, by rights, he ought to be made up. I would have done so, but didn't like to. He looks so severe. Still, for an audition it doesn't matter."

Jo laughed, as she remembered a little scene in Albania. I had been compelled to grow a moustache, as without a moustache I should have been despicable among the mountain chiefs. The moustache had sprouted very bristly and aggressive.

" Is that your husband, madame? " said a Russian officer of King Zog's bodyguard to Jo. " Eh bien, il n'est pas précismént féroce, mais il n'a pas l'air bien commode."

The girl now wanted to try on Jo the effect of the Polish shawl, to which she had taken a fancy. But, just the opposite as in photography, the photomicro cells, which reduce the light-impulses to electric waves, are most highly excited by the colour red. The red flowers were incisible on the white.

" If you look closely," said the young engineer, " you will notice that those big red flowers can just be seen, but actually as lighter spots of white on the white background."

Cora Gordon wearing the dress she made

especially for the TV audition.