Jan Gordon left a prolific amount of biographical writings woven amongst the texts of his writing; It is so so frustrating that he never identified himself or Cora in those writings which would have been an immensely valuable record of those times. It is only by endless re-reading and cross referencing that I have been able to decode and establish certain texts as reasonably likely to have a high degree of verisimilitude to actual fact. Failing any contradiction from any other sources I have to use what I have as given here as Gordon fact.

Below here is an article that Jan Gordon wrote for Blackwoods magazine, the foremost literary periodical of those times in 1929. Why he chose the name Claribel to denote Cora I have no idea, and probably never shall have....and if only he had put a full name to the initialled other personages in the yarn.

It is however a pretty close account of his and Cora's early years in Paris, pre 1914.

GRADUS AD . . . MONTPARNASSUM.

The writer who picks an artist for his hero has, as a rule, a summary way of polishing off his artistic career. He gives him a few years of poverty in an attic, when genius is only recognised by a few equally impecunious companions, but at last blazes into fame and fortune by means of a picture exhibited at one of the great yearly shows.

From thence forward the town is at the artist's feet, dealers wait at his door, sitters clamour for precedence, and he marries the girl whom he was too noble to court in poverty et seq.

The truth is rather different. During twenty years spent behind the artistic scenes I have known only one artist who soared thus suddenly to fame, a young Scandinavian.

His first exhibition at Stockholm thrust him willy nilly into position as a leader of modern Scandinavian art, much indeed to his own astonishment and dismay. On his return to Paris I was congratulating him, but he cut me very short." It is awful," he cried. “It is not pleasant at all. Why, now I shall have to live up to my reputation for the rest of my life. And all I was asking for was a small success on which I could work along."

He saw too truly… The task of living up to a reputation thus suddenly made, with sharp nosed critics and envious rivals watching for the slightest hint, of relaxation, was not wholly enviable. He was condemned to surpass himself for the rest of his career,

Nor had he waited, with nobility, for success before he had married. Quite to the contrary: up to this moment his wife had been supporting him, for she was one or those strong armed Swedish masseuses who are the mainstay of most Swedish painters. The artist is seldom noble. His awe of the future is dim, or he would hardly have chosen such a profession; he seldom suppresses his feelings towards the girl of his choice. At the first sale of a sketch for £10 or so he dives headlong into matrimony, optimistically sure that henceforward sketches at £10 will sell enough of themselves while he is awaiting that soar into fame and fortune which the novelists have foretold for him. Besides, he needs a model, and anybody can calculate that a wife at nothing per hour must come immensely cheaper than a mere professional who demands her wages on Saturday without fail, Or, it he happens to choose a fellow student, she too wants a model, and the having is doubled. And even to save twice as much out of an income of nothing must in the end be a real economy.

In retrospect it is not the final success but precisely the early years of struggle, the lower slopes of Parnassus, which recur to the memory with a pleasing flavour. There is compensation in the slower progress. I myself was not, I admit, an inch more noble than the rest of my species, a portrait commission for £15 being the basis of our domestic calculations. But so horrified was my prospective father in law that he acted in the best of Victorian traditions, and commended Claribel in the future to the care of the Deity, vice himself, resigned. And in the full flush of this doubly romantic event, an artistic wedding and a parental interdiction, oar first exhibition tool, place. It was not, properly speaking, an attack on the portals of fame, but a deliberate and feminine assault on the pockets of the public. I say this in no spirit of Adam and Eve, but I should never have had the good sense to exploit the end of the honeymoon thus. For the assault was directed on Claribel's native place (her father having moved), and it reckoned on the fact that sentiment in such matters rims higher in favour of the feminine half of a newly married couple.

(this tale is similarly given in 'A Girl in the Art Class',by Jan Gordon and refers to Buxton and Cora's father)

An old friend of the family lent us an empty shop for a week, and in the intervals between bride's lunches and bridal dinners we got our premises ready for the grand opening. Our actions excited at first a lot of comment, and even anxiety in the commercial circles. “Was it possible," the gossips asked one another, “ that Miss Claribel, or rather Mrs Salis and her young husband were going to open shop? " (also Buxton)

They trembled at the thought of such unfair competition, for gentle folk would naturally draw the gentry. They wondered where the blow would fall, what commodity were we choosing? But when they learned by devious ways that it was only Art they sighed in relief, and on the penultimate day of the show the butcher himself in ceremonial clothes, with red face atop, and his wife in stiff Sunday satin, dared to look in on us. He removed his hat, exhaled loudly, and after having apologised for his intrusion, added

" Ah tho't maybe Ah might get a little souvenir of Miss Claribel theer if it was about a poond."

Luckily the butcher, previous to taking so temerarious a step, had canvassed the opinions of his customers. "Would it be considered presumptuous?”

We had been warned. There was little in the show to please an English butcher, or at least butcher cum wife, for Claribel's designs were exotic and mostly of semi nude dancers making arabesques of themselves to a counter rhythm of draperies and cats. So a realistic sketch was hurriedly found in the discards. . It consisted of little more than a gate and a turnip field, but the introduction of a girl with a basket made it into a 'figure piece.' Indeed, so well did the butcher's taste agree with that of the general public that several visitors had to be shooed away from it with some tact. As the show drew to its conclusion, we began to wonder if we had not miscalculated the butcher's courage. But on his appearance he was at once conducted to his picture, approved of it, paid his ' poond.' cast troubled eyes at the *exotic dancers, and withdrew with the satisfaction of a bold deed happily accomplished.

* [ some of these 'exotic' designs have recently turned up and are now on site]

Our raid was not in truth very buccaneering, although to many English people a picture exhibition, given by a friend, is little better than an act of aesthetic highwayman-ship. Here at least the strain on the purse was modest, for our pictures were small and our prices to match. One of two larger things gave a certain air of authority to the small sketches, and one in particular, which contained about ten pounds of potatoes elaborately painted in detail before they degenerated from art to the casserole, excited so much interest that we thought it sold a dozen times. A portrait **of Claribel, executed by me in the full glamour of our engagement, delighted one old lady. She fluttered about it for so long that our hearts beat high; the sale would have meant six months of tranquillity for us. But she finally decided not to buy, “because she had no one to whom she could leave it." This post obit interest is an obstacle which an artist meets not seldom; many a promising sale has thus halted at the brink of the grave. And we, young idiots that we were, never thought of suggesting that she might will it back to us. Yet, although we mulcted the town tactfully, we returned to Paris well satisfied with our sentimental experiment, recompensed enough to show Claribel's still repudiating father that the job he had so cursorily confided to the Deity was apparently in capable hands.

**(This portrait of Cora, titled l'Anglaise was known to exist in the 1940's I would love to know its whereabouts now)

The reasons which made us choose Ghent for our next show, for our first real exhibition in fact, wore not actually mysterious, although S---- himself was an odd character. He was a small German Jew brought up in Russia, and the German, the Jewish and the Russian were so inextricably entangled in him that Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was a plain sailing combination in comparison. All the most exaggerated characteristics of each nation fought in him, and in turn had the upper hand. He was married to an American girl, and the facts of his marriage were characteristic. They had met at some artistic reunion, but he could speak no English; she could speak neither French, German, Russian, nor Yiddish. However, he chose to fall passionately in love with her, and, as a natural consequence, she with him. Courtship was reduced to sighs, ogles, and dumb crambo; but love laughs at dictionaries as lightly as at locksmiths. His muted suit was successful. So he learned the pregnant words 'I love you,' and on them played a hundred variations, andante sostentuto, allegreto moderato con expressione fortissimo and all the musical vocabulary. The Luxembourg garden was the scene of this triumph of manner over matter, and he made his formal request 'to name day’ through the mother who had a few sentences of German.

How they got through the ceremony we do not know: but by this time they had invented a polyglot Esperanto most strange to hear, in which English. French, German, Yiddish and Russian served as they came most handy. She, although several years resident in Paris, had such a confusion of European tongues in her head that she could never sort them out, and was almost like the whole of the builders of Babel condensed into one person.

We had not been planning to exhibit again so early in our career, least of all to invade a strange European town with our still modest art. But S -, booked for an exhibition in Gent, was looking for a confrère who would share with him the expenses of the gallery and yet not be a serious rival. Claribel and I filled the bill to a T. He bolstered up our modesty, inflamed our ambition, described Belgium as a country clamouring for art, and pointed out that painting pictures and selling them were two very different branches of the profession, and that it was time we learned the latter. He was right, as we discovered.

(there exists one of Jan's early sketches labelled Gent ;see page 'art of Jan Gordon')

Having lured us in, S-- kindly agreed to save us the expense and bother of having to go to Ghent a week in advance to hang the show.

His Germanic side allowed him to canvass and corner all the possible purchasers, in which he showed a certain frank egoism which came as a complete surprise to us. From being associates we found ourselves suddenly translated into the position of rivals. One thing, however, he did arrange, as it contributed to the general dignity of the exhibition. The show was under the auspices of an art society, and S-- made the president come to the station to greet us. His daughter presented Claribel with a huge bouquet, and then the President, bowing his tall frock coated figure and waving his silk hat solemnly, broke into an English speech.

“Mister Salis," he began, “blimy but h'l'm glad ter see yer. And this I presoom is ther missus. Welcome ter Ghent, Marm, and h'if there's hanythink h'I can blinking well do for yer, gay the word. That's orl, see. Crikey, h'I'm glad ter think as ‘ow you're going ter show yer paintings 'ere. . ."

The perfect Billingsgate of his speech contrasted so oddly with the immaculateness of his costume and the urbanity of his backbone that I could not refrain from a comment on the remarkable character of his English, and inquire how he had attained it.

“Why, blimey," he replied, when h'I was a nipper h'I h'used ter go down to the blooming docks 'ere and get the sailors ter give me lessons. Yer see, Mister Salis, this 'ere h'English not being pronounced like h'it is written, H'it h’is most h’important ,is 'ow a man wot wants to learn correct 'as to get 'is h'accent straight, as you might say. But h'l h'am told h’i 'aye a most h’eccelent year for the h'accent."

"Your ear," I could only answer,” is almost too good. In England we say that when anybody speaks perfect English he is probably a foreigner."

“Why," he replied with some complacency,” that's orl right. Though I 'as ter say 'as 'ow there ain't many wot 'as 'ad my h'opportuntities."

The young painter, cajoled by the novelists, imagines that he has only to paint his pictures; fame and the fervid picture lover do the rest. S--- taught us otherwise. The pictures once painted, the artist has, in the expressive American phrase, to sell himself. It is frankly a Shylockish performance -a pound of soul instead of flesh. The public does not willingly buy mere paint and canvas; why pay ten guineas for a twopennorth of canvas, a sixpennorth of paint and a five shilling frame? The extra ten pounds four shillings odd is paid for a prime cut of your soul; and if the poor artist is at hand and the would be buyer a lady, she insists on having that ten pounds' worth of soul spread out and bleedingly described for her benefit. A sentimental and enthusiastic admirer can make the artist feel more clean stripped and nude than ever was Susannah. That is, if you have an English upbringing, which tends to keep souls clothed as decently as bodies. S -- unblushinglyingly drew dramatic pictures of his soul for the benefit of the Ghent amateurs. He had two kinds of pictures, those he did for reputation and those he did for commerce; but in selling he seemed to have a sardonic zest in spilling more soul over the sale of one potboiler than over that of two of his genuine works, which were very talented in expression.

For instance:" You see that cemetery," he once said to us, pointing out a small sketch (I translate from his Franco German English idiom), “I paint that in Russia one time. But it was so grey, so grey. Then I stop a housepainter who was passing, and I say, 'Hey, how much you take to paint that tomb red?

‘We fix the price, he paint the tombstone, and I finish my picture. But I sometimes wonder what that family think when they come next Sunday and find their tomb all red like that

But to the client: “Ah, Monsieur! Ah Madame yes in very truth. That strange scarlet tomb. Yes, in actual reality. I saw it once passing through at dusk . . . like a blow at my heart, so unexpected, so poignant. I strive to render that sinister effect, that scarlet tombstone all those other pallid grey graves. Exactly, Madame, like a wound.

I tried to render my sensations but only after many inquiries did I find out the reason. The man was murdered, it seems if but his murderer had escaped and they painted it red as a sign till the murderer should be caught; So the man should, as it were cry aloud every week. And perhaps in my soul I heard that cry. And thus, Monsieur I strove that some of this sensation should emanate from the picture . . . The price? . . . ',

We took our souls too seriously and came off badly in the contest.

The lesson of the Gent show lasted us for a couple of years. We continued to paint and to hope and to send to the salons awaiting that burst of critics' clamour which should usher us into the painter’s paradise. A critic, K ----, now made us grasp once more at public approval. K------ ** (actually Andre Salmon) was a young French critic aiming at distinction, and, indeed, on the road to it. He had invented a form of poetic criticism, full of intricate simile, double jointed allusions, and flamboyant imagery, which had the merit of being quite incomprehensible, although it sounded like the most tremendous sense. His prefaces to catalogues were becoming highly appreciated, for they left the reader feeling overawed but somehow unintelligent which was undoubtedly the most profitable frame of mind for the dealer or the artist K ------ since climbed to eminence, the button of the legion of honour, the front page of a great daily, poems in profusion and a number of plays but in those days he clung to a paper which hung on the of bankruptcy and was the author of one slim book of verse in praise of opium dreams a long way after Baudelaire.

K---- had been of service to a gentleman who owned an Art gallery, and from time to time he was able to introduce friends to the place. It was not essentially, we think, our Art that made K -- choose us for one such exhibition. He was the perfect Frenchman, and we attracted him for much the reasons that Othello attracted Desdemona. Claribel's exotic drawings stimulated the imagist side of his nature, while I " Voyageur dans les Indes comme un heros de Kipling,*" to quote from his preface had a glamour; he surrounded me in his exuberant fancy with tigers and boa constrictors, thrust me into the arms of impossible ebony Cleopatras, and rooted a whirlwind admiration of my present in the illusion of my past.

*[referring to Jan's past adventures in the Malay]

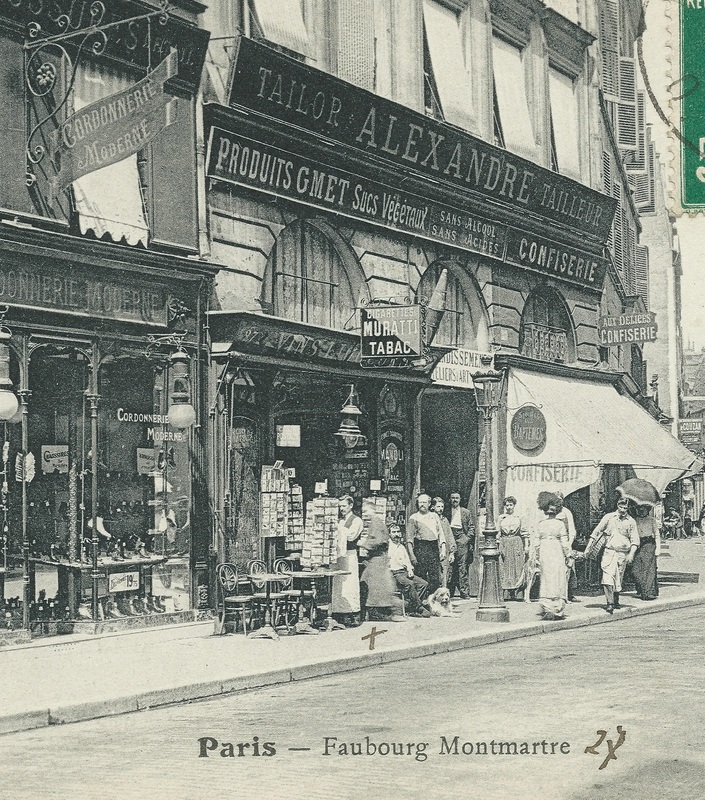

The owner of the gallery, M ---, ** (Galerie des Arts Henri Manuel, 27 rue Faubourg Montmartre) was not a conventional art dealer: he was a fashionable photographer, who had the ingenious idea of transforming his huge waiting rooms into a gallery of painting, thus not only befriending painters but amusing patrons. At least he assured a continual flux of visitors, which is more than many galleries assure. Sometimes, as for us, he launched his shows with a gala, at which wore present members of the Ministry, of the Chambre des Deputés, of the Stock Exchange and of the Stage, for he took the photographs even of minor celebrities free. We too were given carte blanche, but could do no better than distribute invitations round Montparnasse. We spent the last of our resources on frames, and once more waited for the warm embrace of fame and fortune.

The opening night arrived. We dined at home on bread and cheese, calculating to make up on M ---'s generous provisions. We arrived at the gallery, were shown up. At the door K-- met us, tearing his hair; behind him loomed M----ploughing deep lanes through his immense black beard with his fingers.

“Ah, mes amis. I weep for you. Ah, what tragedy," cried K ----.

“But what is it " we exclaimed.

“But is it possible? You do not know, then ? All is lost," shouted M --, waving his arms.

“What, what? “we implored.

The gallery was there, our pictures wore there, we could see nothing to excite this greeting of disaster.

“But, sacré bleu," cried K ---, " the Ministry has fallen ',

Fate was determined to keep us lingering on her doorstep. The diplomats, the Stock Exchange, the Stage . . . what indeed are art exhibitions when the Ministry falls.

For a Frenchman of affairs to look at a picture during such a crisis would be as bad as was the conduct of Nero at the fire of Rome. No audience was left to us but the hordes of Montparnasse, who fell joyously on M 's champagne, and gobbled his luxurious tit bits with a will. K -- himself was so agitated that in attempting to recite aloud his poetical preface he misjudged his strength, and with the words: " Voyageur dans les Indes comme, un heros de Kipling," he fell fainting into the arms of a bystander, and was with difficulty restored to consciousness by the hysterics of his wife.

The show was, however, noticed favourably one of a thousand others per annum several of the big Parisian dailies; and amongst smaller pickings Claribel sold one important picture, It was a big exuberant drawing in colour of the Cleopatra cum anachronism period ; the buyer wrote her a letter in which he explained that he was a diplomat, that he kept a salon that received beaucoup de monde that the drawings would be well placed, and that she in consequence would derive high benefits from his possession of it. In view of these benefits he could not offer more, than about a third of the catalogue price. Claribel hesitated. But after all to sell a picture . . . to sell it, to a stranger . . . on its merits . . . without that of oneself . . . even at a third of the price. The diplomat got his picture and did not invite us over to see how it was hung. Beaucoup de monde have gazed on it, but, for all the benefit that it brought to Claribel it might as well have been dropped to the bottom of the sea of oblivion. Sometimes we wonder where it is now. Odd thought: little bits of ourselves drifting about the world, housed by strangers

Not long ago I found in California a sketch which I had first sold in London.

Sheer poverty was responsible our fourth exhibition; we were stoney broke. So once more this time under the aegis of a well to do American friend, we made a deliberate assault on the pockets of the public: in this instance her rich friends. Our studio was an immense barn of a place which subsequently has become a public garage. Various friends agreed to live the show a start. One was a singer since risen to fame; another knew a young Spanish dancer and a Spaniard who played the guitar; he could also arrange candles in old biscuit boxes so as to give the effects of footlights. Unluckily, hinds were wanting either for the piano or the refreshments. The piano company, in the days before the war, was trustful. It allowed us the piano on tick. We explained the situation to the épicier who lived only three doors away; we had no money, but promised payment on results. He temporised. He would come and the pictures first and decide if they merited the risk. He came, inspected our art, weighed it, in a critical mind, and sent in more lavishly than we had ordered

On the afternoon before the opening Claribel's ex artmaster came to inspect us. He was A ---, famous painter of the Salon National. We hung on his opinion, for we were in truth still but little better than students in spite of our past shows. Behind a screen our charwoman was washing up. She, too, had had a long acquaintance with studios, and knew how important this visit was to us. But A - was almost too enthusiastic. He had not seen our work for over a year, and he burst into Gallic expressions of delight at our progress. Our char was a long fuzzy haired Italian woman, and each of A ---'s " Ah Mais” her tousled head popped up over the screen and an expressive eye gave us a great wink of delighted sympathy. As soon as A had taken his leave, she, rushed out to congratulate us. But we shook our beads sadly at one another.

"If that had only been tomorrow," said Claribel's ex artmaster, "each of those 'Ah mais' would have been worth at least twenty francs. Now they have all been wasted."

The transatlantic lambs were, led to the shearing, and lost their wool with a good

The singer sang, the dancer danced, the cakes were eaten and that very night paid for.

We went to bed solvent but nauseated. For six hours we bad been so seeped with lavish compliments that we were sticky with them. They were but the sincere efforts of nice honest folk to show us that they, too, had souls; they were the attempts of aspirants struggling to live for a moment up to what they imagined the artist to be; but who little knew that except for a capacity to put shapes and colours together the artist also is quite an ordinary man, and has, when he is honest, quite an ordinary soul.

One lady, a poetess with a taste for the esoteric and its accompanying trimmings swore that De M--- the, great French actor, must see Claribel's drawings. ( actually Edouard de Max , a flamboyant homosexual actor of Rumanian descent, photo below)

But, alas! De M--- was in bed. He had been overset by Apaches and slightly injured. So, since De M--- could not come to the show, the show must go to De M---- . The poetess called for Claribel in a cab, the more exotic and esoteric of the drawings were thrust in after them, and off they went.

Claribel was left in an antechamber while the poetess prepared the actor. She found herself in the midst of a weird collection. A Balzac would be needed to catalogue it; objects of vertu were crowded on every hand, but all had been picked for some sinister or erotic, quality. Through the flat the dividing walls had been removed, and their places were taken by curtains of a strange livid yellow, supported by twisted pillars of old wood painted a bright sky blue. At intervals a creaking voice uttered French words of considerable impropriety. The poetess lingering, Claribel looked about her for the origin of the voice. She pushed the curtain at the other end of the room and saw a bathroom. The bath was scooped ill the black marble floor. At its edge a huge black mastiff lay, gnawing and slobbering over a raw bone the fresh meal; on which showed startlingly crimson against the black polished floor. Behind the dog on a swinging perch a gaudy parrot ignorantly uttered French obscenities with all a parrot's air of wisdom.

At last she was summoned, and, traversing half a dozen rooms all of a similar character, was ushered into the actor's bedroom. He lay in a Chinese bed of carved ebony. His fine though heavy face and neck made think of Emperors He was shrouded in a gown of vivid orange satin, and he pawed over the drawings with a sensuous appreciation. Some were decorations for fans decorations for and the odd crinkled quality of one he particularly admired. Claribel could not toll him that for want of material they had been painted on the silk of discarded blouses and petticoats, and that the peculiar quality he was admiring had been achieved simply.

It was a piece, of old washed petticoat; that, she had been to impatient too iron smooth

( pre 1914 Cora exhibited a number of fan paintings on silk; one such Salon Nationale des Beaux-Arts 1912 #2540. illustrations, ,'Midsummer nights dream' for a poem by Fritz Vanderpyl and #2541 La Nuit, a silk fan; a poor photo of one of these fans see page 'art of Cora Gordon' on here)

Over one drawing he became lyric. In the manner of the aesthetic Frenchman he began to build up a rhetorical monument to it.

He seemed to perceive a hundred strange aspects of which Claribel had not the slightest idea when she had drawn the thing. Then in a burst of enthusiasm he proposed that she should design a ballet for him, and at once he began to improvise the details. However, the poetess cut him short. She told him that Claribel was a nice English lady and had been so well brought up that she could not even understand what he was talking about. Which was true. This so deflated the great actor that his inspiration vanished, and, ordering his valet to pay the price of the drawing, he let Claribel go.

But as she went he assured that her picture should have a place of honour; in fact right above his pillow, Claribel came home wondering just what she had put in that drawing, and somewhat startled at her own unsuspected capacity.

Below here is an article that Jan Gordon wrote for Blackwoods magazine, the foremost literary periodical of those times in 1929. Why he chose the name Claribel to denote Cora I have no idea, and probably never shall have....and if only he had put a full name to the initialled other personages in the yarn.

It is however a pretty close account of his and Cora's early years in Paris, pre 1914.

GRADUS AD . . . MONTPARNASSUM.

The writer who picks an artist for his hero has, as a rule, a summary way of polishing off his artistic career. He gives him a few years of poverty in an attic, when genius is only recognised by a few equally impecunious companions, but at last blazes into fame and fortune by means of a picture exhibited at one of the great yearly shows.

From thence forward the town is at the artist's feet, dealers wait at his door, sitters clamour for precedence, and he marries the girl whom he was too noble to court in poverty et seq.

The truth is rather different. During twenty years spent behind the artistic scenes I have known only one artist who soared thus suddenly to fame, a young Scandinavian.

His first exhibition at Stockholm thrust him willy nilly into position as a leader of modern Scandinavian art, much indeed to his own astonishment and dismay. On his return to Paris I was congratulating him, but he cut me very short." It is awful," he cried. “It is not pleasant at all. Why, now I shall have to live up to my reputation for the rest of my life. And all I was asking for was a small success on which I could work along."

He saw too truly… The task of living up to a reputation thus suddenly made, with sharp nosed critics and envious rivals watching for the slightest hint, of relaxation, was not wholly enviable. He was condemned to surpass himself for the rest of his career,

Nor had he waited, with nobility, for success before he had married. Quite to the contrary: up to this moment his wife had been supporting him, for she was one or those strong armed Swedish masseuses who are the mainstay of most Swedish painters. The artist is seldom noble. His awe of the future is dim, or he would hardly have chosen such a profession; he seldom suppresses his feelings towards the girl of his choice. At the first sale of a sketch for £10 or so he dives headlong into matrimony, optimistically sure that henceforward sketches at £10 will sell enough of themselves while he is awaiting that soar into fame and fortune which the novelists have foretold for him. Besides, he needs a model, and anybody can calculate that a wife at nothing per hour must come immensely cheaper than a mere professional who demands her wages on Saturday without fail, Or, it he happens to choose a fellow student, she too wants a model, and the having is doubled. And even to save twice as much out of an income of nothing must in the end be a real economy.

In retrospect it is not the final success but precisely the early years of struggle, the lower slopes of Parnassus, which recur to the memory with a pleasing flavour. There is compensation in the slower progress. I myself was not, I admit, an inch more noble than the rest of my species, a portrait commission for £15 being the basis of our domestic calculations. But so horrified was my prospective father in law that he acted in the best of Victorian traditions, and commended Claribel in the future to the care of the Deity, vice himself, resigned. And in the full flush of this doubly romantic event, an artistic wedding and a parental interdiction, oar first exhibition tool, place. It was not, properly speaking, an attack on the portals of fame, but a deliberate and feminine assault on the pockets of the public. I say this in no spirit of Adam and Eve, but I should never have had the good sense to exploit the end of the honeymoon thus. For the assault was directed on Claribel's native place (her father having moved), and it reckoned on the fact that sentiment in such matters rims higher in favour of the feminine half of a newly married couple.

(this tale is similarly given in 'A Girl in the Art Class',by Jan Gordon and refers to Buxton and Cora's father)

An old friend of the family lent us an empty shop for a week, and in the intervals between bride's lunches and bridal dinners we got our premises ready for the grand opening. Our actions excited at first a lot of comment, and even anxiety in the commercial circles. “Was it possible," the gossips asked one another, “ that Miss Claribel, or rather Mrs Salis and her young husband were going to open shop? " (also Buxton)

They trembled at the thought of such unfair competition, for gentle folk would naturally draw the gentry. They wondered where the blow would fall, what commodity were we choosing? But when they learned by devious ways that it was only Art they sighed in relief, and on the penultimate day of the show the butcher himself in ceremonial clothes, with red face atop, and his wife in stiff Sunday satin, dared to look in on us. He removed his hat, exhaled loudly, and after having apologised for his intrusion, added

" Ah tho't maybe Ah might get a little souvenir of Miss Claribel theer if it was about a poond."

Luckily the butcher, previous to taking so temerarious a step, had canvassed the opinions of his customers. "Would it be considered presumptuous?”

We had been warned. There was little in the show to please an English butcher, or at least butcher cum wife, for Claribel's designs were exotic and mostly of semi nude dancers making arabesques of themselves to a counter rhythm of draperies and cats. So a realistic sketch was hurriedly found in the discards. . It consisted of little more than a gate and a turnip field, but the introduction of a girl with a basket made it into a 'figure piece.' Indeed, so well did the butcher's taste agree with that of the general public that several visitors had to be shooed away from it with some tact. As the show drew to its conclusion, we began to wonder if we had not miscalculated the butcher's courage. But on his appearance he was at once conducted to his picture, approved of it, paid his ' poond.' cast troubled eyes at the *exotic dancers, and withdrew with the satisfaction of a bold deed happily accomplished.

* [ some of these 'exotic' designs have recently turned up and are now on site]

Our raid was not in truth very buccaneering, although to many English people a picture exhibition, given by a friend, is little better than an act of aesthetic highwayman-ship. Here at least the strain on the purse was modest, for our pictures were small and our prices to match. One of two larger things gave a certain air of authority to the small sketches, and one in particular, which contained about ten pounds of potatoes elaborately painted in detail before they degenerated from art to the casserole, excited so much interest that we thought it sold a dozen times. A portrait **of Claribel, executed by me in the full glamour of our engagement, delighted one old lady. She fluttered about it for so long that our hearts beat high; the sale would have meant six months of tranquillity for us. But she finally decided not to buy, “because she had no one to whom she could leave it." This post obit interest is an obstacle which an artist meets not seldom; many a promising sale has thus halted at the brink of the grave. And we, young idiots that we were, never thought of suggesting that she might will it back to us. Yet, although we mulcted the town tactfully, we returned to Paris well satisfied with our sentimental experiment, recompensed enough to show Claribel's still repudiating father that the job he had so cursorily confided to the Deity was apparently in capable hands.

**(This portrait of Cora, titled l'Anglaise was known to exist in the 1940's I would love to know its whereabouts now)

The reasons which made us choose Ghent for our next show, for our first real exhibition in fact, wore not actually mysterious, although S---- himself was an odd character. He was a small German Jew brought up in Russia, and the German, the Jewish and the Russian were so inextricably entangled in him that Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was a plain sailing combination in comparison. All the most exaggerated characteristics of each nation fought in him, and in turn had the upper hand. He was married to an American girl, and the facts of his marriage were characteristic. They had met at some artistic reunion, but he could speak no English; she could speak neither French, German, Russian, nor Yiddish. However, he chose to fall passionately in love with her, and, as a natural consequence, she with him. Courtship was reduced to sighs, ogles, and dumb crambo; but love laughs at dictionaries as lightly as at locksmiths. His muted suit was successful. So he learned the pregnant words 'I love you,' and on them played a hundred variations, andante sostentuto, allegreto moderato con expressione fortissimo and all the musical vocabulary. The Luxembourg garden was the scene of this triumph of manner over matter, and he made his formal request 'to name day’ through the mother who had a few sentences of German.

How they got through the ceremony we do not know: but by this time they had invented a polyglot Esperanto most strange to hear, in which English. French, German, Yiddish and Russian served as they came most handy. She, although several years resident in Paris, had such a confusion of European tongues in her head that she could never sort them out, and was almost like the whole of the builders of Babel condensed into one person.

We had not been planning to exhibit again so early in our career, least of all to invade a strange European town with our still modest art. But S -, booked for an exhibition in Gent, was looking for a confrère who would share with him the expenses of the gallery and yet not be a serious rival. Claribel and I filled the bill to a T. He bolstered up our modesty, inflamed our ambition, described Belgium as a country clamouring for art, and pointed out that painting pictures and selling them were two very different branches of the profession, and that it was time we learned the latter. He was right, as we discovered.

(there exists one of Jan's early sketches labelled Gent ;see page 'art of Jan Gordon')

Having lured us in, S-- kindly agreed to save us the expense and bother of having to go to Ghent a week in advance to hang the show.

His Germanic side allowed him to canvass and corner all the possible purchasers, in which he showed a certain frank egoism which came as a complete surprise to us. From being associates we found ourselves suddenly translated into the position of rivals. One thing, however, he did arrange, as it contributed to the general dignity of the exhibition. The show was under the auspices of an art society, and S-- made the president come to the station to greet us. His daughter presented Claribel with a huge bouquet, and then the President, bowing his tall frock coated figure and waving his silk hat solemnly, broke into an English speech.

“Mister Salis," he began, “blimy but h'l'm glad ter see yer. And this I presoom is ther missus. Welcome ter Ghent, Marm, and h'if there's hanythink h'I can blinking well do for yer, gay the word. That's orl, see. Crikey, h'I'm glad ter think as ‘ow you're going ter show yer paintings 'ere. . ."

The perfect Billingsgate of his speech contrasted so oddly with the immaculateness of his costume and the urbanity of his backbone that I could not refrain from a comment on the remarkable character of his English, and inquire how he had attained it.

“Why, blimey," he replied, when h'I was a nipper h'I h'used ter go down to the blooming docks 'ere and get the sailors ter give me lessons. Yer see, Mister Salis, this 'ere h'English not being pronounced like h'it is written, H'it h’is most h’important ,is 'ow a man wot wants to learn correct 'as to get 'is h'accent straight, as you might say. But h'l h'am told h’i 'aye a most h’eccelent year for the h'accent."

"Your ear," I could only answer,” is almost too good. In England we say that when anybody speaks perfect English he is probably a foreigner."

“Why," he replied with some complacency,” that's orl right. Though I 'as ter say 'as 'ow there ain't many wot 'as 'ad my h'opportuntities."

The young painter, cajoled by the novelists, imagines that he has only to paint his pictures; fame and the fervid picture lover do the rest. S--- taught us otherwise. The pictures once painted, the artist has, in the expressive American phrase, to sell himself. It is frankly a Shylockish performance -a pound of soul instead of flesh. The public does not willingly buy mere paint and canvas; why pay ten guineas for a twopennorth of canvas, a sixpennorth of paint and a five shilling frame? The extra ten pounds four shillings odd is paid for a prime cut of your soul; and if the poor artist is at hand and the would be buyer a lady, she insists on having that ten pounds' worth of soul spread out and bleedingly described for her benefit. A sentimental and enthusiastic admirer can make the artist feel more clean stripped and nude than ever was Susannah. That is, if you have an English upbringing, which tends to keep souls clothed as decently as bodies. S -- unblushinglyingly drew dramatic pictures of his soul for the benefit of the Ghent amateurs. He had two kinds of pictures, those he did for reputation and those he did for commerce; but in selling he seemed to have a sardonic zest in spilling more soul over the sale of one potboiler than over that of two of his genuine works, which were very talented in expression.

For instance:" You see that cemetery," he once said to us, pointing out a small sketch (I translate from his Franco German English idiom), “I paint that in Russia one time. But it was so grey, so grey. Then I stop a housepainter who was passing, and I say, 'Hey, how much you take to paint that tomb red?

‘We fix the price, he paint the tombstone, and I finish my picture. But I sometimes wonder what that family think when they come next Sunday and find their tomb all red like that

But to the client: “Ah, Monsieur! Ah Madame yes in very truth. That strange scarlet tomb. Yes, in actual reality. I saw it once passing through at dusk . . . like a blow at my heart, so unexpected, so poignant. I strive to render that sinister effect, that scarlet tombstone all those other pallid grey graves. Exactly, Madame, like a wound.

I tried to render my sensations but only after many inquiries did I find out the reason. The man was murdered, it seems if but his murderer had escaped and they painted it red as a sign till the murderer should be caught; So the man should, as it were cry aloud every week. And perhaps in my soul I heard that cry. And thus, Monsieur I strove that some of this sensation should emanate from the picture . . . The price? . . . ',

We took our souls too seriously and came off badly in the contest.

The lesson of the Gent show lasted us for a couple of years. We continued to paint and to hope and to send to the salons awaiting that burst of critics' clamour which should usher us into the painter’s paradise. A critic, K ----, now made us grasp once more at public approval. K------ ** (actually Andre Salmon) was a young French critic aiming at distinction, and, indeed, on the road to it. He had invented a form of poetic criticism, full of intricate simile, double jointed allusions, and flamboyant imagery, which had the merit of being quite incomprehensible, although it sounded like the most tremendous sense. His prefaces to catalogues were becoming highly appreciated, for they left the reader feeling overawed but somehow unintelligent which was undoubtedly the most profitable frame of mind for the dealer or the artist K ------ since climbed to eminence, the button of the legion of honour, the front page of a great daily, poems in profusion and a number of plays but in those days he clung to a paper which hung on the of bankruptcy and was the author of one slim book of verse in praise of opium dreams a long way after Baudelaire.

K---- had been of service to a gentleman who owned an Art gallery, and from time to time he was able to introduce friends to the place. It was not essentially, we think, our Art that made K -- choose us for one such exhibition. He was the perfect Frenchman, and we attracted him for much the reasons that Othello attracted Desdemona. Claribel's exotic drawings stimulated the imagist side of his nature, while I " Voyageur dans les Indes comme un heros de Kipling,*" to quote from his preface had a glamour; he surrounded me in his exuberant fancy with tigers and boa constrictors, thrust me into the arms of impossible ebony Cleopatras, and rooted a whirlwind admiration of my present in the illusion of my past.

*[referring to Jan's past adventures in the Malay]

The owner of the gallery, M ---, ** (Galerie des Arts Henri Manuel, 27 rue Faubourg Montmartre) was not a conventional art dealer: he was a fashionable photographer, who had the ingenious idea of transforming his huge waiting rooms into a gallery of painting, thus not only befriending painters but amusing patrons. At least he assured a continual flux of visitors, which is more than many galleries assure. Sometimes, as for us, he launched his shows with a gala, at which wore present members of the Ministry, of the Chambre des Deputés, of the Stock Exchange and of the Stage, for he took the photographs even of minor celebrities free. We too were given carte blanche, but could do no better than distribute invitations round Montparnasse. We spent the last of our resources on frames, and once more waited for the warm embrace of fame and fortune.

The opening night arrived. We dined at home on bread and cheese, calculating to make up on M ---'s generous provisions. We arrived at the gallery, were shown up. At the door K-- met us, tearing his hair; behind him loomed M----ploughing deep lanes through his immense black beard with his fingers.

“Ah, mes amis. I weep for you. Ah, what tragedy," cried K ----.

“But what is it " we exclaimed.

“But is it possible? You do not know, then ? All is lost," shouted M --, waving his arms.

“What, what? “we implored.

The gallery was there, our pictures wore there, we could see nothing to excite this greeting of disaster.

“But, sacré bleu," cried K ---, " the Ministry has fallen ',

Fate was determined to keep us lingering on her doorstep. The diplomats, the Stock Exchange, the Stage . . . what indeed are art exhibitions when the Ministry falls.

For a Frenchman of affairs to look at a picture during such a crisis would be as bad as was the conduct of Nero at the fire of Rome. No audience was left to us but the hordes of Montparnasse, who fell joyously on M 's champagne, and gobbled his luxurious tit bits with a will. K -- himself was so agitated that in attempting to recite aloud his poetical preface he misjudged his strength, and with the words: " Voyageur dans les Indes comme, un heros de Kipling," he fell fainting into the arms of a bystander, and was with difficulty restored to consciousness by the hysterics of his wife.

The show was, however, noticed favourably one of a thousand others per annum several of the big Parisian dailies; and amongst smaller pickings Claribel sold one important picture, It was a big exuberant drawing in colour of the Cleopatra cum anachronism period ; the buyer wrote her a letter in which he explained that he was a diplomat, that he kept a salon that received beaucoup de monde that the drawings would be well placed, and that she in consequence would derive high benefits from his possession of it. In view of these benefits he could not offer more, than about a third of the catalogue price. Claribel hesitated. But after all to sell a picture . . . to sell it, to a stranger . . . on its merits . . . without that of oneself . . . even at a third of the price. The diplomat got his picture and did not invite us over to see how it was hung. Beaucoup de monde have gazed on it, but, for all the benefit that it brought to Claribel it might as well have been dropped to the bottom of the sea of oblivion. Sometimes we wonder where it is now. Odd thought: little bits of ourselves drifting about the world, housed by strangers

Not long ago I found in California a sketch which I had first sold in London.

Sheer poverty was responsible our fourth exhibition; we were stoney broke. So once more this time under the aegis of a well to do American friend, we made a deliberate assault on the pockets of the public: in this instance her rich friends. Our studio was an immense barn of a place which subsequently has become a public garage. Various friends agreed to live the show a start. One was a singer since risen to fame; another knew a young Spanish dancer and a Spaniard who played the guitar; he could also arrange candles in old biscuit boxes so as to give the effects of footlights. Unluckily, hinds were wanting either for the piano or the refreshments. The piano company, in the days before the war, was trustful. It allowed us the piano on tick. We explained the situation to the épicier who lived only three doors away; we had no money, but promised payment on results. He temporised. He would come and the pictures first and decide if they merited the risk. He came, inspected our art, weighed it, in a critical mind, and sent in more lavishly than we had ordered

On the afternoon before the opening Claribel's ex artmaster came to inspect us. He was A ---, famous painter of the Salon National. We hung on his opinion, for we were in truth still but little better than students in spite of our past shows. Behind a screen our charwoman was washing up. She, too, had had a long acquaintance with studios, and knew how important this visit was to us. But A - was almost too enthusiastic. He had not seen our work for over a year, and he burst into Gallic expressions of delight at our progress. Our char was a long fuzzy haired Italian woman, and each of A ---'s " Ah Mais” her tousled head popped up over the screen and an expressive eye gave us a great wink of delighted sympathy. As soon as A had taken his leave, she, rushed out to congratulate us. But we shook our beads sadly at one another.

"If that had only been tomorrow," said Claribel's ex artmaster, "each of those 'Ah mais' would have been worth at least twenty francs. Now they have all been wasted."

The transatlantic lambs were, led to the shearing, and lost their wool with a good

The singer sang, the dancer danced, the cakes were eaten and that very night paid for.

We went to bed solvent but nauseated. For six hours we bad been so seeped with lavish compliments that we were sticky with them. They were but the sincere efforts of nice honest folk to show us that they, too, had souls; they were the attempts of aspirants struggling to live for a moment up to what they imagined the artist to be; but who little knew that except for a capacity to put shapes and colours together the artist also is quite an ordinary man, and has, when he is honest, quite an ordinary soul.

One lady, a poetess with a taste for the esoteric and its accompanying trimmings swore that De M--- the, great French actor, must see Claribel's drawings. ( actually Edouard de Max , a flamboyant homosexual actor of Rumanian descent, photo below)

But, alas! De M--- was in bed. He had been overset by Apaches and slightly injured. So, since De M--- could not come to the show, the show must go to De M---- . The poetess called for Claribel in a cab, the more exotic and esoteric of the drawings were thrust in after them, and off they went.

Claribel was left in an antechamber while the poetess prepared the actor. She found herself in the midst of a weird collection. A Balzac would be needed to catalogue it; objects of vertu were crowded on every hand, but all had been picked for some sinister or erotic, quality. Through the flat the dividing walls had been removed, and their places were taken by curtains of a strange livid yellow, supported by twisted pillars of old wood painted a bright sky blue. At intervals a creaking voice uttered French words of considerable impropriety. The poetess lingering, Claribel looked about her for the origin of the voice. She pushed the curtain at the other end of the room and saw a bathroom. The bath was scooped ill the black marble floor. At its edge a huge black mastiff lay, gnawing and slobbering over a raw bone the fresh meal; on which showed startlingly crimson against the black polished floor. Behind the dog on a swinging perch a gaudy parrot ignorantly uttered French obscenities with all a parrot's air of wisdom.

At last she was summoned, and, traversing half a dozen rooms all of a similar character, was ushered into the actor's bedroom. He lay in a Chinese bed of carved ebony. His fine though heavy face and neck made think of Emperors He was shrouded in a gown of vivid orange satin, and he pawed over the drawings with a sensuous appreciation. Some were decorations for fans decorations for and the odd crinkled quality of one he particularly admired. Claribel could not toll him that for want of material they had been painted on the silk of discarded blouses and petticoats, and that the peculiar quality he was admiring had been achieved simply.

It was a piece, of old washed petticoat; that, she had been to impatient too iron smooth

( pre 1914 Cora exhibited a number of fan paintings on silk; one such Salon Nationale des Beaux-Arts 1912 #2540. illustrations, ,'Midsummer nights dream' for a poem by Fritz Vanderpyl and #2541 La Nuit, a silk fan; a poor photo of one of these fans see page 'art of Cora Gordon' on here)

Over one drawing he became lyric. In the manner of the aesthetic Frenchman he began to build up a rhetorical monument to it.

He seemed to perceive a hundred strange aspects of which Claribel had not the slightest idea when she had drawn the thing. Then in a burst of enthusiasm he proposed that she should design a ballet for him, and at once he began to improvise the details. However, the poetess cut him short. She told him that Claribel was a nice English lady and had been so well brought up that she could not even understand what he was talking about. Which was true. This so deflated the great actor that his inspiration vanished, and, ordering his valet to pay the price of the drawing, he let Claribel go.

But as she went he assured that her picture should have a place of honour; in fact right above his pillow, Claribel came home wondering just what she had put in that drawing, and somewhat startled at her own unsuspected capacity.

Next year we decided to try our own London with portfolios under our arms we entered a well known gallery and asked to see the manager. It was our first attempt on an art dealer's; (This would be the Bailly Gallery, 13 Bruton street, London and their exhibition in Nov 1912 , Watercolours Etchings and Fans by Mr and Mrs Jan Gordon" Cora's work was very favourably reviewed but Jan's somewhat less ) no friend stood beside us, no critic had recommended us. The director looked at our paintings and we too gazed at them miserably.

There is a telepathy at such a moment. Never do one's own pictures look so worthless as when a dealer is considering them.

But to our astonishment he, turned to us with a kindly smile and said

“That’s all right. Now when can you be ready?” But there, with the opening of the regular dealer's door the romance of picture showing fades away. Exhibiting becomes a mere monotonous interlude in the artist’s career. But if he is lucky he will never have to exchange those first adventurous, exciting steps at the foot of Montparnassus for any of the novelist’s glamorous crash into fame. For in real life glamour is like the child's jam: the more it is spread out the sweeter it tastes.

Jan Gordon writing as SALIS in Blackwoods Magazine March 1929

The pen name John Salis was adopted by him during his days writing art criticism for the New Witness and similar. He explains in his diaries that it was chosen because "all art criticism should be taken with a large pinch of salt."

There is a telepathy at such a moment. Never do one's own pictures look so worthless as when a dealer is considering them.

But to our astonishment he, turned to us with a kindly smile and said

“That’s all right. Now when can you be ready?” But there, with the opening of the regular dealer's door the romance of picture showing fades away. Exhibiting becomes a mere monotonous interlude in the artist’s career. But if he is lucky he will never have to exchange those first adventurous, exciting steps at the foot of Montparnassus for any of the novelist’s glamorous crash into fame. For in real life glamour is like the child's jam: the more it is spread out the sweeter it tastes.

Jan Gordon writing as SALIS in Blackwoods Magazine March 1929

The pen name John Salis was adopted by him during his days writing art criticism for the New Witness and similar. He explains in his diaries that it was chosen because "all art criticism should be taken with a large pinch of salt."